The Curious Case of the City of Everett

By Denise Ohio

Published by Holy Toledo

www.everettmassacre.com/curious-cases.html

2020 Denise Ohio

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-7351200-1-0

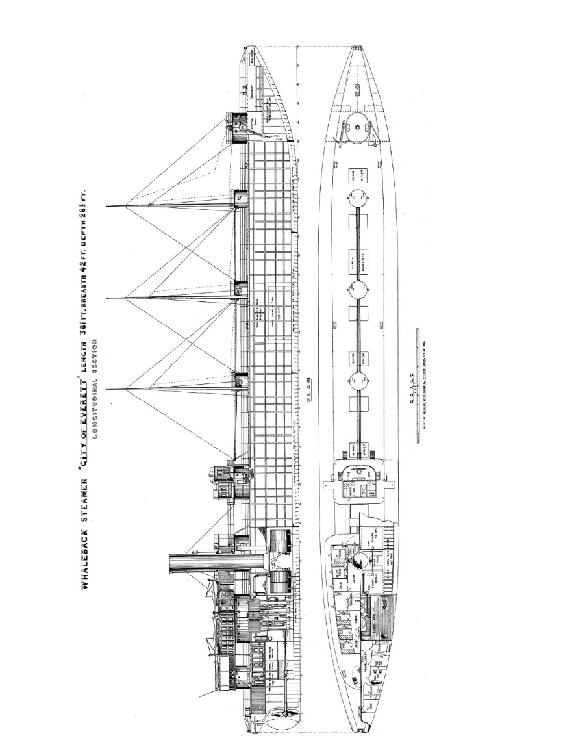

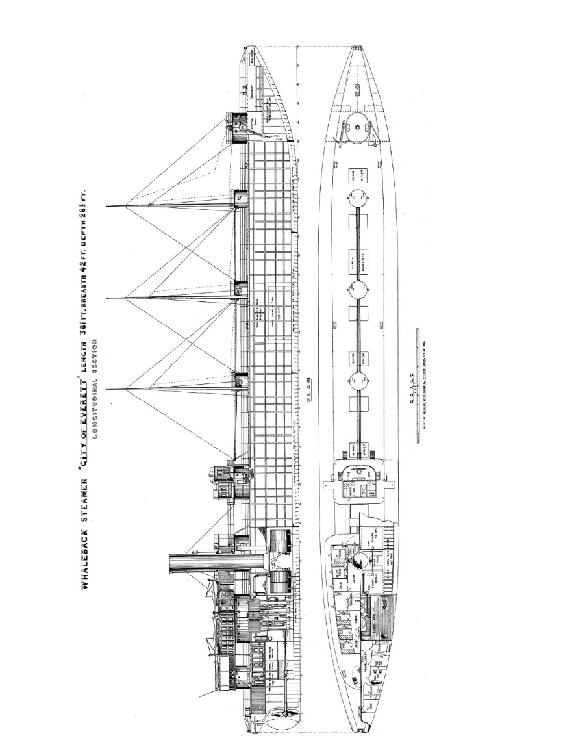

The City of Everett in the lift drydock at the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California. Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command, United States Navy.

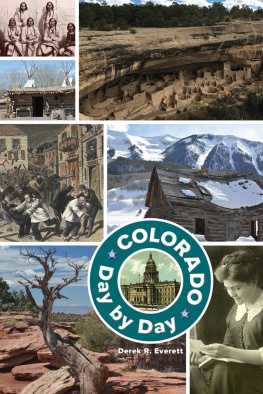

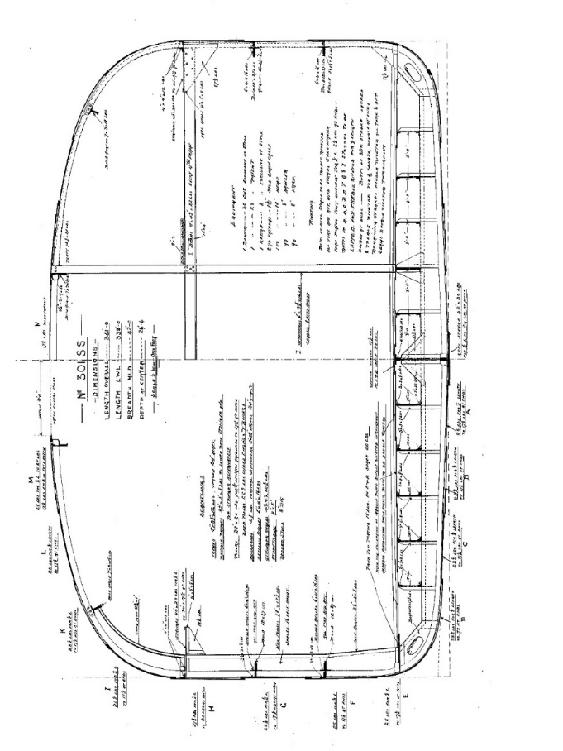

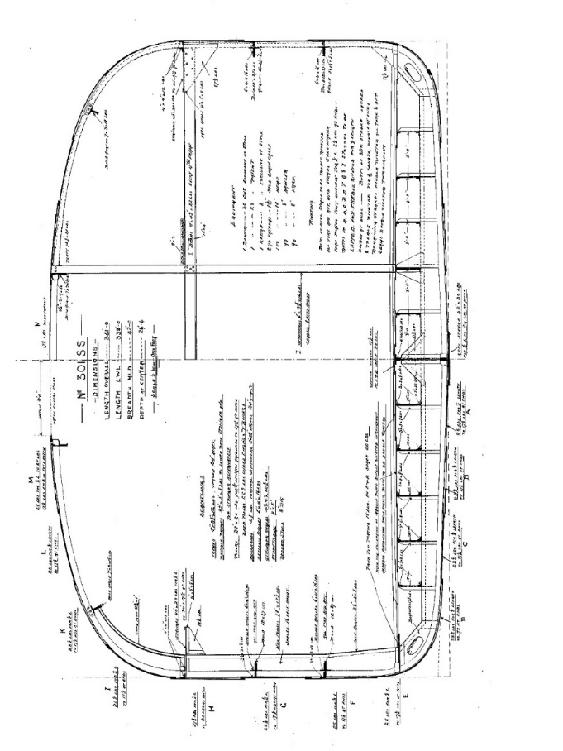

Original plans for the City of Everett. Courtesy of the Historical Collections of the Great Lakes, Bowling Green State University.

In 1898, sometime between the sinking of the Maine and Teddy Roosevelts charge up San Juan Hill, the merchant ship City of Everett, according to the tale, captured the Spanish city of Mlaga. As told by Captain Tom Fenlon, when the ship dropped anchor in quarantine, no one showed up until the next morning. Important citizens dazzling in gold braid rowed out, climbed onto the deck, and delivered a series of flowery speeches in a language that Fenlon didnt understand. A crewman finally translated that Spain and the United States were now at war and Mlaga had surrendered. When Fenlon recovered from his shock, he promised he would return the city without violence if his crew could fill the ships fresh water tanks. The tanks were filled, celebration ensued, and the following morning, Fenlon did what any merchant mariner would do: he sailed for home.

It seems an unlikely story, but unlikely things happen during war. And the 1890s were filled with unlikely stories about men with names like Ransford Dodsworth Bucknam and beards and mustaches that suggest styling facial hair was a leading form of entertainment. The tale was so improbable, so Marx Brothers, like a big joke that it had to be true: the best citizens of a large and ancient city surrender to a bunch of clueless sailors who hadnt taken a bath or brushed their teeth in weeks. Old World pomp collides with New World bewilderment.

Mlaga, Spain, waterfront. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

It was absurd, yet people believe the story. But theres no evidence that Mlaga surrendered to the City of Everett. There are no newspaper reports, official documents, or letters home to support the tale. Though the Marine Review would later report the City of Everett was the last US ship out of a Spanish port before the outbreak of hostilities, an archivist for the city of Mlaga found no mention in the city records of gold-braided officials bending the knee to a merchant sea captain.

The tale first appeared in 1958 in Captain Thomas Fenlon, Master Mariner, a fictionalized account of Captain Fenlons life by Garland Roark. The book is not good, which is too bad because Tom Fenlon sounds like an interesting guy. Born in 1867 in New York City, he ran away from an orphanage at the age of eight and had to eat out of garbage cans and sleep in an empty piano box until he got a job tending mules that hauled barges on the Erie Canal. He later worked as a steersman on a canal boat, a deckhand on a clipper ship that stranded him in China, and an oyster pirate in Chesapeake Bay. By twenty-five, he had a masters license for both sail and steam.

Original hull detail for the City of Everett. Courtesy of the Historical Collections of the Great Lakes, Bowling Green State University.

Fenlon eventually did become master of the City of Everett. That part of the story is true. The ship was a whaleback and generated interest in every port because of its unusual design, one that the inventor, Alexander McDougall, just knew was the future of shipping. Whalebacks had a cheap- and easy-to-build steel hull with a convex top, straight sides, a conical bow, and a flat bottom. Imagine an uppercase D with the flat part of the letter facing down with the top deck only six feet above the water, and a ships bridge at the back. While the deck had turrets, most of the ship lay below the water, minimizing friction and letting the ship travel heavy seas without reducing speed.

Not everyone was enamored of McDougalls design. He spent his own money to build his first whaleback barge and his success gained him the attention of moneymen like John D. Rockefeller and Charles Wetmore of Standard Oil, and Colgate Hoyt and Charles Colby of the Northern Pacific Railway. They formed the American Steel Barge Company with a yard in Duluth, Minnesota, then later moved to Superior, Wisconsin, and would build more than forty whalebacks between 1888 and 1898. While the American Steel Barge Company built ships for the Great Lakes, McDougall looked west. There was opportunity in coastal and Pacific trade, and he and his partners joined Henry Hewitt Jr. to build a new city on Puget Sound that they named Everett, after Charles Colbys fifteen-year-old son. The moneymen slapped their names on city streets that hadnt even been built yet and persuaded others to build factories in the new town.

The Pacific Steel Barge Works on the Snohomish River in Everett, Washington. Courtesy of the Northwest Room, Everett Public Library.

McDougall was firmly convinced Everett was a better choice for a port than Seattle or Tacoma. His reasons had nothing to do with geography or how easily men like Rockefeller could bend opponents to their will or land prices or the coming of James J. Hills Great Northern Railway. He was convinced Everett would become a world-class port because of the teredo.

The teredo is a small, wormlike, saltwater clam that bores through wood. Fourteen-foot tidal changes meant most Puget Sound ports had to build massive docks on large, expensive, wooden pilings, and the teredo meant those structures had to be replaced frequently. But this wasnt a problem at Everett: the Snohomish River emptied fresh water into Port Gardner Bay, making it uninhabitable for the species.

This was such a benefit to shipping that McDougall was sure someone would dredge channels to make the entire waterfront navigable by oceangoing ships. Then the nascent West Coast ship-building industry would dominate Asian markets, especially if it relied on his whaleback designs.

Inside the hull of the City of Everett at the Pacific Steel Barge Works. Courtesy of the Northwest Room, Everett Public Library.

McDougalls investors agreed, and in 1892 they formed the Pacific Steel Barge Company, built a shipyard on the Snohomish River in north Everett, and immediately put almost two hundred men to work on the saltwater cargo ship City of Everett. But the Silver Panic of 1893 brought ruin. Across the country, banks closed, businesses shut, and one out of every three workers was suddenly unemployed. Work at the Everett shipyard slowed to a crawl, but McDougall didnt give up. The City of Everett was launched on October 10, 1894, though the ship lacked engines, crew quarters, the bridge, and even the ships wheel.