For Madeline and Katherine, who amaze me in even more ways than the things I write about.

VIKING

An Imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2015

Smithsonian

Smithsonian

trademark is owned by the Smithsonian Institution and is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Smithsonian Enterprises:

Christopher Liedel, President

Carol LeBlanc, Senior Vice President, Education and Consumer Products

Brigid Ferraro, Vice President, Education and Consumer Products

Ellen Nanney, Licensing Manager

Kealy Gordon, Product Development Manager

Dr. Katherine Ott, Curator, Division of Medicine and Science, National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center, Smithsonian

Copyright 2015 by HP Newquist, Penguin Random House LLC, and Smithsonian Institution

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

ISBN 978-1-101-99714-7

PHOTO CREDITS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

.

Version_1

Introduction

HUMAN BEINGS HAVE FILLED THE world with complex machines, intricate devices, and awe-inspiring structures. These things range from rockets and robots to supercomputers and skyscrapers. They are all remarkable for the incredible amount of thought that went into their design and construction and the millions of parts it took to build them.

For all their impressiveness, not one of them comes close to the sheer complexity of the human body.

Nothing else in the known universe has as many pieces and working parts as each one of us. There are trillions of connections in your brain. More than a hundred thousand miles of blood vessels traverse every part of your body. You have a heart that beats about 35 million times a year, and eyes that blink ten thousand times a day. Enough blood to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool pumps through your body every year. There are more than two dozen primary organs keeping you alive and 206 bones holding you together.

Yet you dont control any of this. Your inner workings, for the most part, began operating long before you were actually born. On the other hand, it is up to you to make sure that they keep working efficiently by keeping your body healthy.

The human body is one of the universes greatest machines, with millions of moving parts working together every minute of every day. Yet like even the best of machines, it occasionally breaks. It gets damaged in accidents. It slows down or wears out as it gets older. Since the beginning of recorded history, people have attempted to fix their broken parts. Inventors have tried to replace, support, or improve upon nearly every organ, limb, bone, and tissue that make up the human form. Truth be told, science has done a pretty good job of repairing just about everything in our bodies.

The inventions described in the following pages have had an impact on the way we think about our bodies, how we treat them, and what we treat them with. Were going to see how flesh and bone have given way to wood and metal, glass and gold, carbon fiber and computers. This is a story of humans trying to understand exactly what other humans are made of, and trying to make things better when they go wrong.

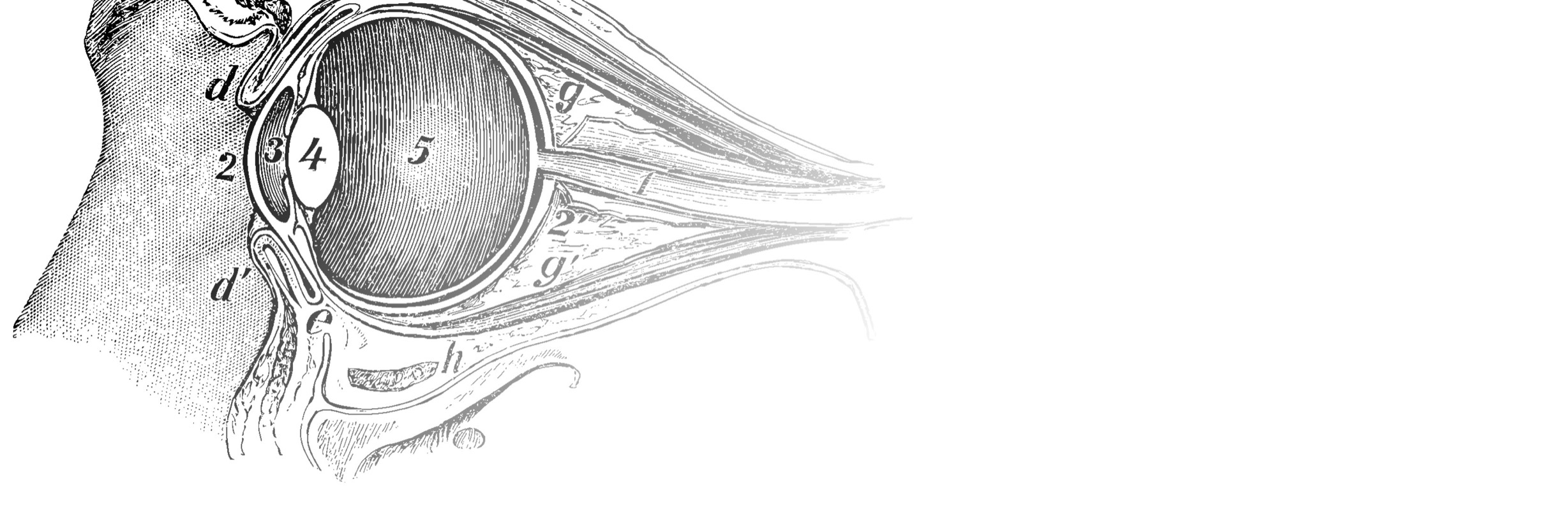

Eyes

MOST OF WHAT WE KNOW about the world enters our brain through our senses. Eyes have a major role in processing information. Every eye is an extremely intricate organ, containing two types of photoreceptors that detect light: about 120 million rods for seeing black and white and 6 million cones for seeing color. Eyes are so complex and do so much work that even the slightest change to their functionality is noticeable. Losing the actual eye can be catastrophic.

Since the earliest days of the human race, eyes lost to war, disease, hunting, farming, or accidents left gaping holes in the eye sockets, which could also endanger surrounding tissue. To present a less startling face to the outside world, people either covered the hole with an eye patch or replaced the eye itself with a replica. Unlike most prostheses, an eye replica is not functional. It only serves to make people look better and feel less self-conscious about having an empty eye socket.

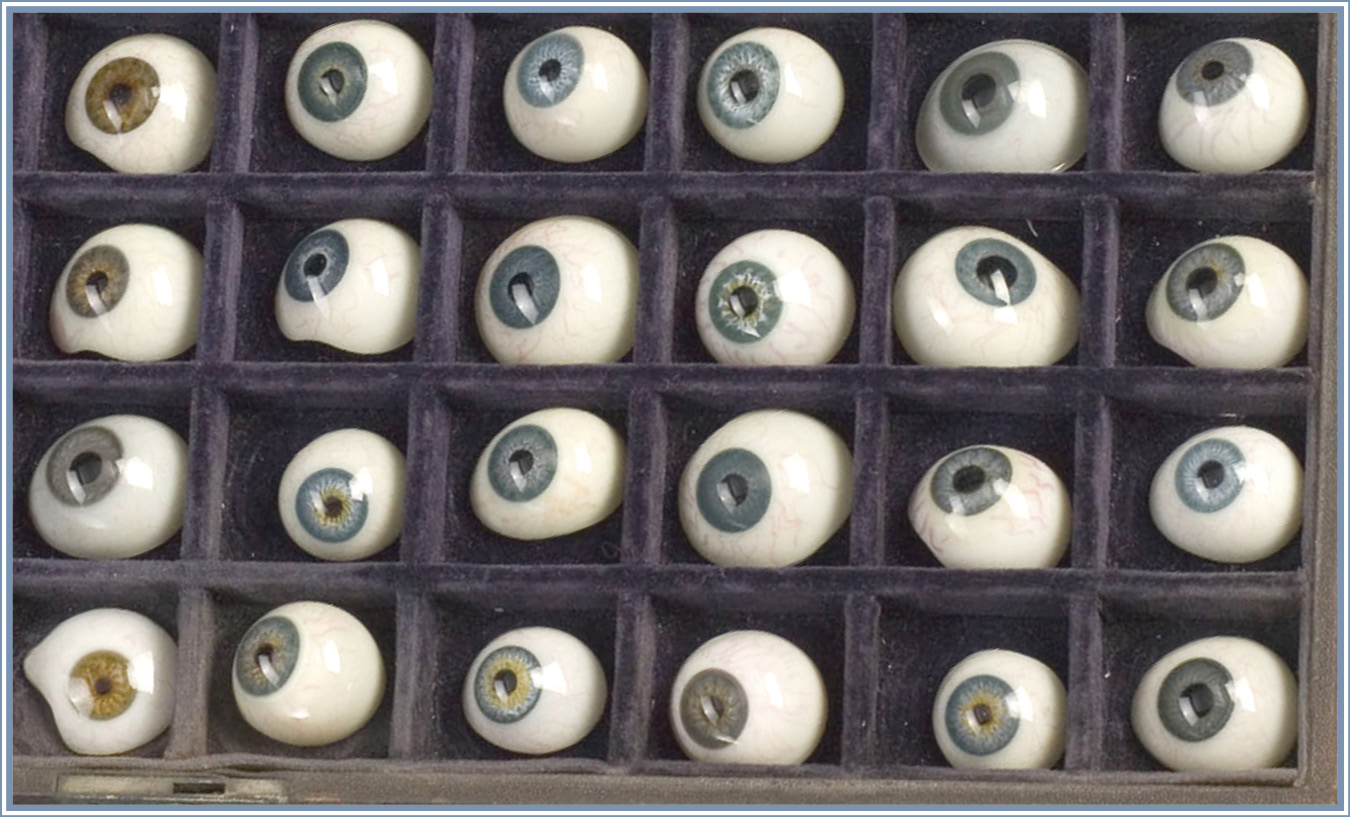

People have used fake eyes for centuries. These artificial eyes were made of a wide variety of materials, depending on what the eyeless person could afford: gold, porcelain, enamel, glass, cork, rubber, sponge, wax, bone, or wool. The oldest fake eye known was discovered in 2007 in present-day Iran. It was found in the skeleton of a Persian priestess or fortune-teller who lived five thousand years ago. Her eye was made of a cement-like mixture and coated with gold. She probably wore it so that she had two eyes when she made public appearanceswhere a glittering gold eye most likely awed her followers.

By the seventeenth century, glass was the material of choice for fake eyes. Italian glassmakers in Venice became known for their realistic glass eyes, orbs slightly smaller than a Ping-Pong ball that could be popped in and out of the wearers eye socket with little difficulty. Glass eyes looked more realistic than those made of other materials and were more comfortable. Irises on the glass eye were painted to match the wearers other eye, and tiny blood vessels were drawn on to add to the realism. Unfortunately, the glass globes would occasionally burst in the eye sockets if wearers bumped their heads or if the temperature changed dramatically when they went in or out of a building.

Realistic-looking glass eyes were often made using thin tubes of glass. One end of the tube was superheated, and the other end was blown into until a ball formed at the hot end. Colored glass was added to achieve a lifelike effect.

Glass eyes remained the preferred type of artificial orb until World War II (19391945). Glass eyes from Germany, the largest maker of them, became unavailable to America and much of Europe during the war. So they turned to plastic. Acrylic glass, a tough plastic better known as Plexiglas, proved to be even better for creating lifelike eyes. After the war, acrylic eyes were mass-produced in just a few sizes, and patients bought them hoping for the best look and fit.

Smithsonian

Smithsonian