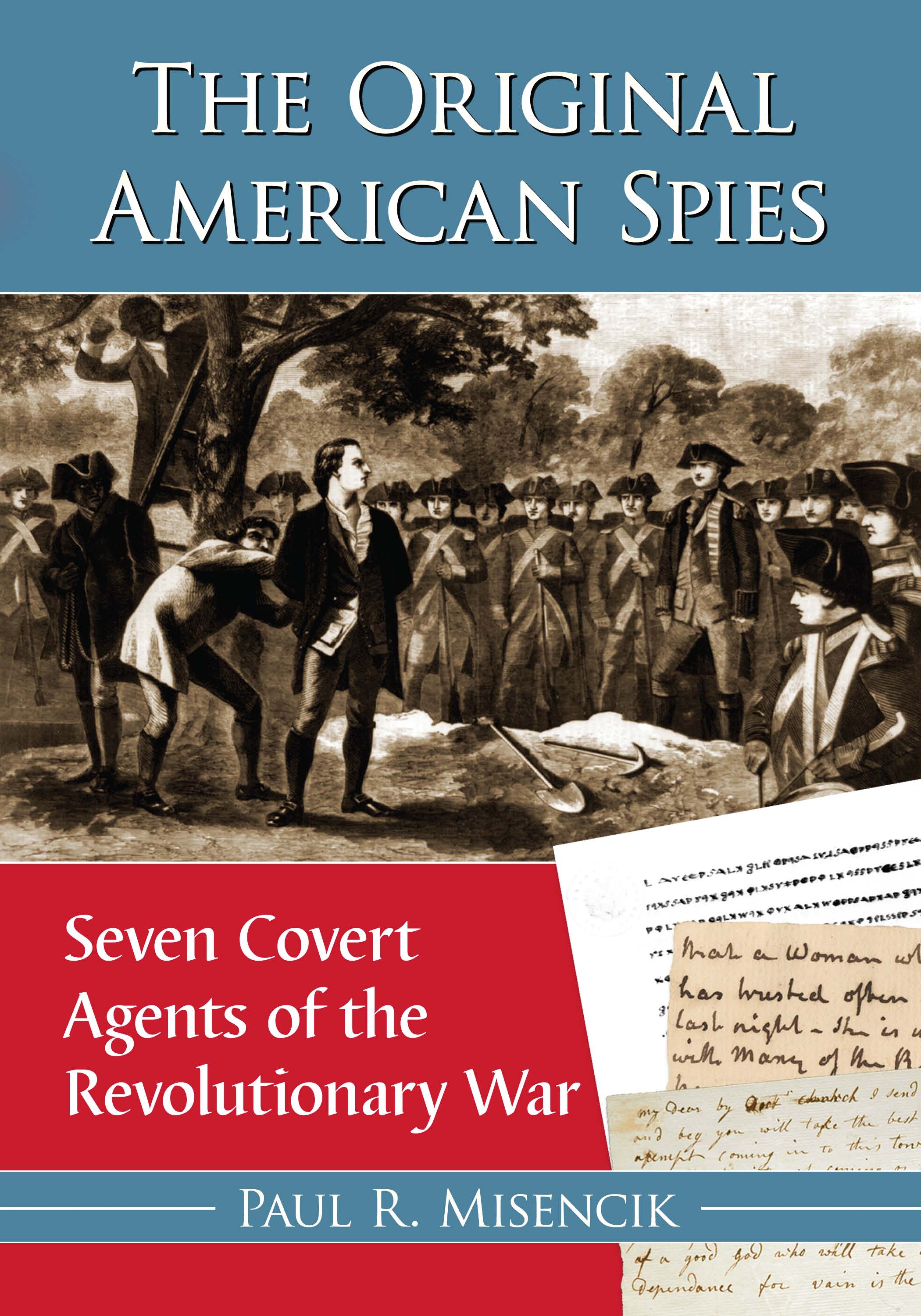

Also by PAUL R. MISENCIK

George Washington and the Half-King Chief Tanacharison: An Alliance That Began the French and Indian War (McFarland, 2014)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1291-1

2014 Paul R. Misencik. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

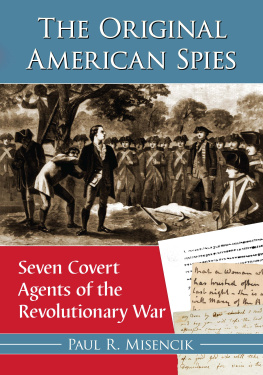

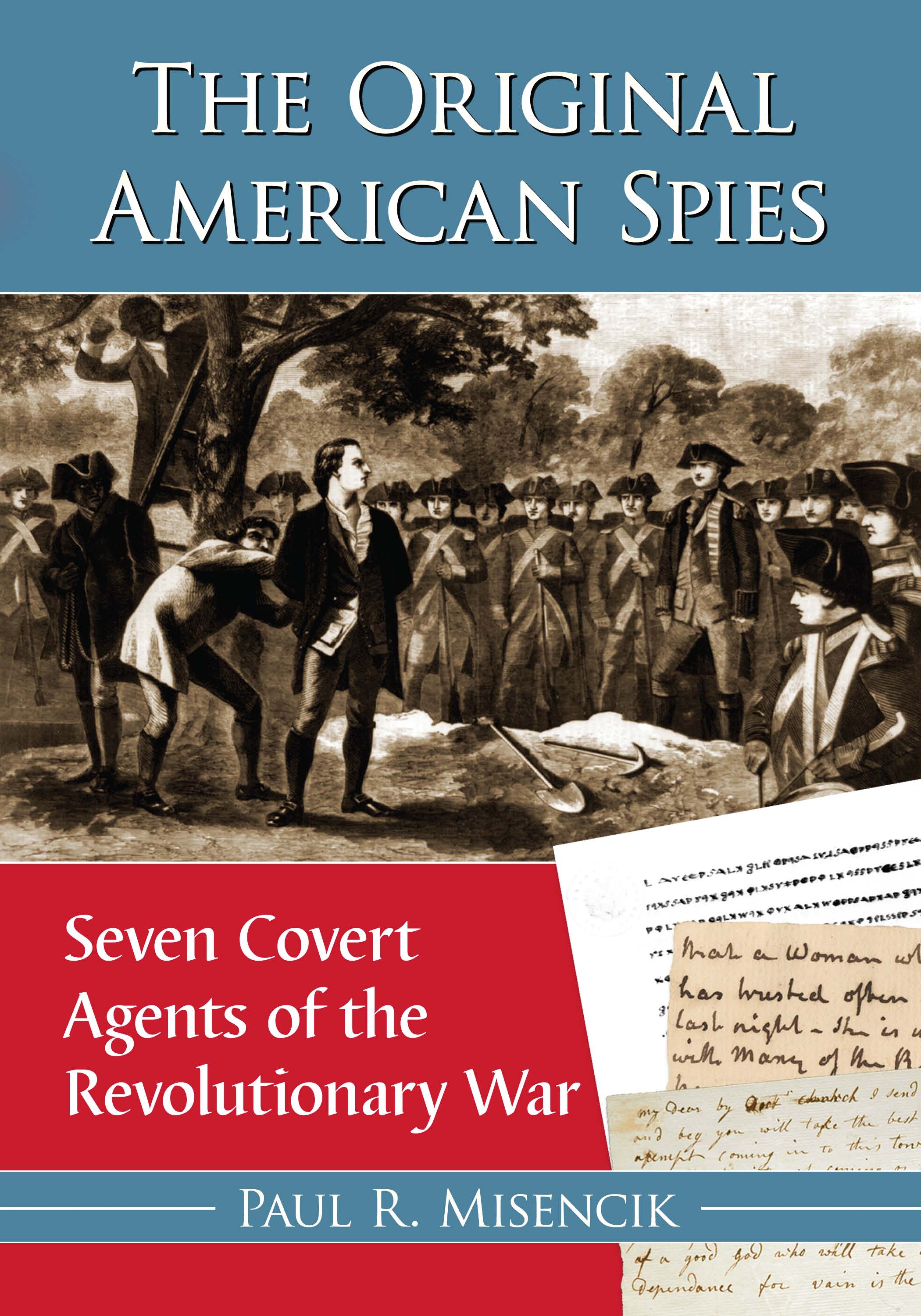

On the cover: background execution of Nathan Hale on the site of east Broadway, corner of Market Street, New York, September 21, 1776 (Library of Congress); foreground, front to back detail of letter from Rachel Revere to Paul Revere (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan), detail of letter from Major Duncan Drummond to General Clinton regarding Ann Bates (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan), detail of coded letter from Benjamin Church, Jr., to Maurice Caine, July 1775 (Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, 17411799, Series 4, General Correspondence, 16971799)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Sally, my beautiful companion and

enthusiastic advocate who loves

the adventure of research as much as I do.

No one could ask for more.

Preface

Nearly 400,000 troops were engaged at one time or another during the eight long years of the American Revolutionary War. Indeed, even before the shot heard round the world was fired on Lexington Green, individuals from all strata of society found themselves drawn into the battle. Not all of them were male and not all wore uniforms. The participation of these non-soldiers often proved very significant for their respective sides, and in many cases their lives were fraught with more peril than the average uniformed soldier on the traditional battlefield. This book is about seven such individuals who fought on a far different battlefield, and whose adventures offer a compelling and fascinating glimpse at the Revolutions secret war.

They were perhaps the most unlikely participants in the American Revolution; a 21-year-old Connecticut school teacher, a middle-aged Philadelphia Quaker housewife, a famous Boston surgeon, the charming wife of a soldier, a quiet New Jersey butcher, a flamboyant New York clothier and raconteur, and the most successful newspaper publisher in the North American colonies. They were a diverse lot, coming from different locations, circumstances and backgrounds, yet for their own private reasons, they all took part in what one of them referred to as a peculiar service; they were spies.

These individuals voluntarily engaged in the perilous and clandestine world of espionage knowing that failure would likely be fatal and conceivably result in suffering and hardship for their families and friends. Not all were motivated by patriotism, and not all escaped capture, but all were daring, intelligent and resourceful, and each had a unique and enigmatic personality, which makes their experiences all the more fascinating. Their labors resulted in battlefield victories, thwarted enemy plots, and significantly changed the conduct of the war, yet in spite of their efforts, they and their deeds have remained relatively unknown.

Some of the names mentioned in this book are recognizable, but few people are aware of their extraordinary narratives. For example, most people may be familiar with the death of the young spy Nathan Hale who paraphrased Joseph Addisons Cato when he said, I regret that I have but one life to give for my country, but few know about Nathan Hales short but remarkable life, the ironic circumstances of his capture, or the impact of his death on future American espionage missions.

Spying during the 18th century was generally considered an abhorrent or at least a less than honorable activity, which accounts for the mean death by hanging accorded to captured agents. To be a spy required a rather unique personality in order to effectively function in the curious world of deceit, false allegiance and betrayal. It also required a taste for a somewhat bizarre and macabre type of adventure.

Not everyone was suited for or attracted to such a devious occupation. Few had the predilection for espionage and fewer yet had the necessary temperament and skills to be successful and, more important, to escape exposure. Eighteenth century spies received little if any training and generally learned by experience and developed their own techniques. They often were alone and deep within enemy territory and their survival depended on their quick wits, composure under extreme pressure, adaptability and resourcefulness. Some successfully evaded capture while others did not, and the difference between success and failure was frequently razor-thin and more often determined by luck. These were seven real people whose challenges, accomplishments, and occasional failures actually happened, but whose exploits were often stranger than fiction.

1

The First Spy: Captain Nathan Hale (17551776)

Almost everyone familiar with the history of the American Revolutionary War knows how General George Washington skillfully marched, countermarched, feinted and parried his outnumbered and lesser-trained forces across the middle colonies until he gradually wore down and eventually defeated the mighty British army. Most people, however, are not as familiar with George Washington the spymaster who personally directed dozens of espionage elements during the Revolutionary War. Washingtons first painful military experiences two decades earlier, during the French and Indian War, taught him the necessity of obtaining accurate information regarding his opponents. Indeed, soon after he took command of the American forces at Cambridge in 1775, Washington realized that any hope of success against the British military would require accurate and timely intelligence, and from the early days of the war, the commander-in-chief advocated development of an effective espionage network.

Unfortunately, Washingtons first attempt to place a spy behind enemy lines was a disaster brought about by a series of unfortunate circumstances exacerbated by amateur planning and execution. To his credit and ultimate success, Washington learned from his mistakes and through his direct, personal involvement the American espionage efforts gained in sophistication and expertise that eventually yielded significant intelligence results. This is the story of Nathan Hale, Washingtons first known spy. He was the first of many secret agents, both American and British, who served their respective causes for their own personal reasons during the American Revolutionary War.

Nathan Hale was born on Friday, June 6, 1755, in Coventry, Connecticut, the sixth of twelve children born to Richard and Elizabeth Strong Hale who were both Puritans committed to religious devotion, personal integrity and education. Nathans father Richard was a prosperous farmer who was a pillar of the community and a deacon in the church. Though Nathan was a sickly child in his early years, he grew into a strong, healthy and very intelligent young man. He was described as strikingly handsome, with a slender build, fair skin, a ruddy complexion, light hair, clear, light blue eyes and a soft, musical voice. He was taller than the average height, growing to just under six feet tall. He had what was described as a cheerful and generous manner, naturally at ease with social graces, and was mature beyond his years. He was popular in his community and one acquaintance, Dr. Aeneas Munson, described Nathan Hale as a diamond of the first water, calculated to excel in any station he assumes. He is a gentleman and a scholar, and last, though not the least of his qualifications, a Christian. Nathans parents encouraged education for everyone in the family and arranged for young Nathan to be tutored by the local minister, the Rev. Dr. Joseph Huntington.

Next page