A CKNOWLEDGEMENT IS DUE TO the publishers for permission to quote from the following books: to George Allen & Unwin Ltd for The Supreme Command by Lord Hankey; to Geoffrey Bles Ltd for The Memoirs of Marshal Joffre by Marshal J. J. C. Joffre, translated by Colonel T. Bentley Mott; to Jonathan Cape Ltd for Prelude to Victory by Major-General E. L. Spears; to Eyre & Spottiswoode Ltd for The Private Papers of Douglas Haig, edited by R. Blake; and to Hutchinson and Co. Ltd for General Headquarters, 19141916 by General E. von Falkenhayn, and for My War Memoirs by General E. von Ludendorff. Acknowledgement is also due to Christy & Moore Ltd for permission to quote from A Frenchman in Khaki by Paul Maze.

The Author and Publishers also wish to thank the following for permission to reproduce illustrations which appear in this book: the Radio Times Hulton Picture Library for Figs 5 and 6; Ulstein Bilderdienst, Berlin, for Fig. 3; and the Imperial War Museum for the remainder of the photographs.

The maps on pages are based on the map The Somme 1916 in Official History of the Great War, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1916, by permission of Her Majestys Stationery Office.

CONTENTS

A Family Perspective

A S THE E ASTER T ERM of 1963 drew to a close at Exeter School, my thoughts turned to a new and intriguing opportunity. My father had invited me to join him on a journey to the Somme to complete research on his latest book. For my part, a minor role emerged, charting our journey and points of key interest with my trusty box brownie camera.

After an uneventful journey across the Channel, we found ourselves on a foggy evening looking for our B&B on the AlbertBapaume road. Over the next ten days, we began by exploring the operations of Fourth Army, first from the German perspective, before going on to examine aspects of the British advance in September 1916. As a schoolboy, the sheer scale of operations; the extraordinary endurance of fighting men gathered from every corner of the Empire; the daily routine in appalling conditions; and the shocking loss of human life took a while to sink in. Sobering thoughts for a future Sandhurst cadet!

Walking across the battlefield at High Wood, my father dropped into the conversation that his uncle Stanley Griffin had fought in the battle. A young officer in the Machine Gun Corps, commanding a platoon of four Vickers machine guns, he had been seriously wounded in the stomach late on 1 July and was fortunate to be helped to a dressing station.

Some seventy years later, when my great uncle came to stay for a few days, my wife asked him over breakfast what he might like to do today. Well, he said, I wondered whether we might go to Mersea Island. Of course, she replied. Is there anything in particular you would like to see? We were living just outside Colchester. A journey to Mersea was but 3 miles. I would like to stand on the jetty and look out to sea

As the story unfolded, we heard of two brothers determining what they might do in the summer holidays of 1914. On 3 August, Stanley and Bernard arrived late in the afternoon at Burnham on Crouch on the Essex coast. The following morning they hired a dinghy. Their goal was Mersea Island. It was a beautiful day and they exulted in a shared love of sailing. Approaching the island the jetty now in sight they were surprised to see a boy in short trousers, running down the jetty as though towards them. Suddenly he stopped and, cupping his hands, shouted the immortal words: Wars declared!

With scarcely a further thought, they turned about, retracing their steps to Burnham and thence to Hamilton Road in Ealing and an uncertain future. Bernard, older by three years, joined the Middlesex Regiment, moving to Sittingbourne before embarking on a troopship for India in October 1914 with 1/10th Battalion (Territorial Force). Stanley initially mustered with 3rd Battalion, York & Lancaster Regiment, before transferring to the Machine Gun Corps in November 1915.

On Stanley Griffins ninetieth birthday, our children experienced a fleeting moment of revelation from him, so rare in men of that generation. Who shall say what triggered it? From his subconscious memory there unfurled a scene on the village green in Ealing. Clasping his hands to his ears in despair at the insistent peal of church bells, he had tugged at his mothers skirts in a moment of desperation; only to learn of the relief of the siege of a place beyond his wildest imagination called Mafeking.

As the evening wore on, he reflected on how fortunate he had been to see old age; to have survived the tumult of the Somme; to be carried to a dressing station and given life-saving surgery. And then to see it all happen again in 1939. It was an enormous span of history for any of us to absorb, gathered around my fathers dinner table.

A week after my return from the Falklands War in 1982, I was delighted to hear my great uncles voice on the telephone. Now we had a shared experience minor though mine was in any realistic comparison. Little needed to be said. He was glad of my safe return and simply wondered whether some music would help to heal the soul: an offer to go with him to the Albert Hall, which I readily accepted.

Major General Dair Farrar-Hockley MC

November 2015

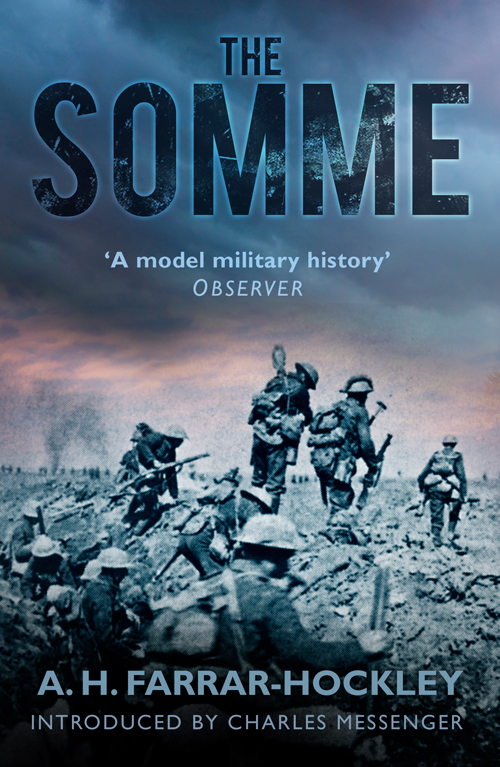

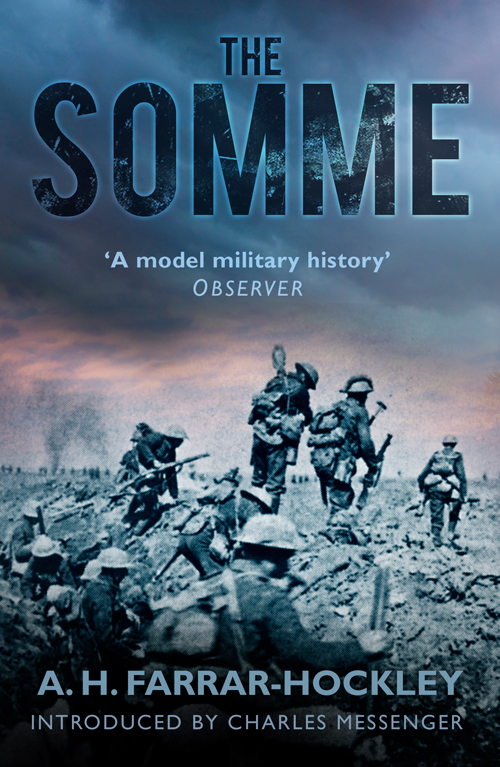

I C OUNT M YSELF P RIVILEGED to have been trained in part by General Sir Anthony Farrar-Hockley GBE KC B DSO MC when I was an officer cadet at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. He was then a major, already highly decorated and well known to us cadets through his book The Edge ofthe Sword, which described, often movingly, his Korean War experiences, especially as a prisoner of the Chinese and North Koreans. While at Sandhurst, Tony Farrar-Hockley came to know well Brigadier Peter Young DSO MC, outstanding wartime commando and the academys reader in military history, and the eminent military theorist and soon to be knighted Basil Liddell Hart. It was they who persuaded Farrar-Hockley to take up writing military history. His first attempt, a study of the 1914 campaign written while he was at Sandhurst, never reached publication stage. He worked on this book on the 1916 Somme battle when commanding 3rd Battalion the Parachute Regiment at Aldershot, prior to taking it to the Radfan, where he won a bar to the DSO he had been awarded for Korea.

Farrar-Hockley did not have the advantage that modern historians have of being able to consult official documents. As far as the British were concerned, the fifty-year rule was still in force (it would be reduced to thirty years in 1967), which meant that in 1964, when The Somme was first published, it was only the 1914 papers that were released by the Public Record Office (now The National Archives). It was much the same with the French and Germans. There was also not the wealth of private papers in the public domain as there are now. Instead, Farrar-Hockley had to rely largely on the literature of the day, including the official histories. He did have one benefit that modern historians do not: he was able to talk to a number of British veterans of the battle. These men were then in their late sixties or early seventies and certainly compos mentis. The author also tramped the battlefield, as his son Dair recounts.

As the historiography of the war on the Western Front stood in 1964, the British public certainly was influenced by two books: Leon Wolff s

Next page