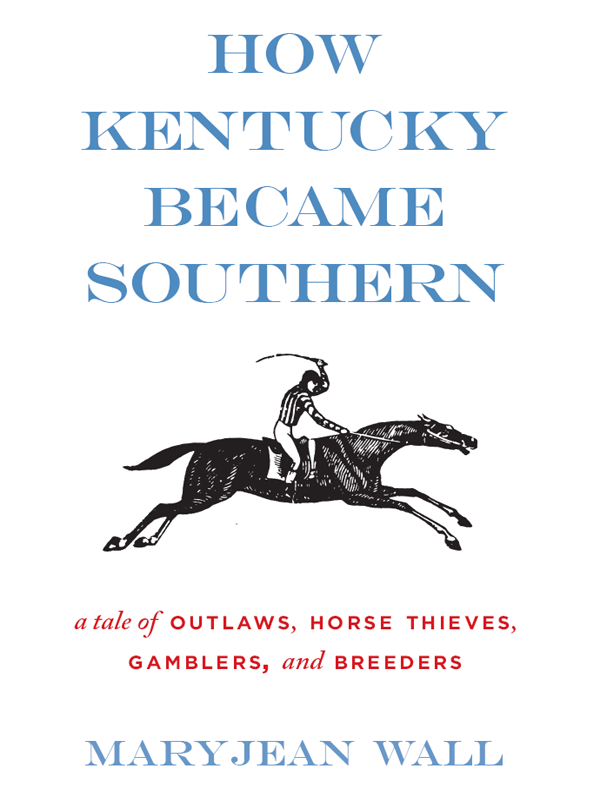

HOW

KENTUCKY

BECAME

SOUTHERN

a tale ofOUTLAWS, HORSE THIEVES, GAMBLERS, andBREEDERS

Maryjean Wall

Copyright 2010 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wall, Maryjean.

How Kentucky became southern: a tale of outlaws, horse thieves, gamblers, and breeders/Maryjean Wall.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-813-12605-0 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Horse racingKentuckyHistory19th century. 2. Horse industryKentuckyHistory19th century. 3. KentuckySocial life and customs19th century. I. Title.

SF335.U6K66 2010

798.40976909034dc22

2010020664

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

To my parents,

John and Mary Wall,

who believed in education

Contents

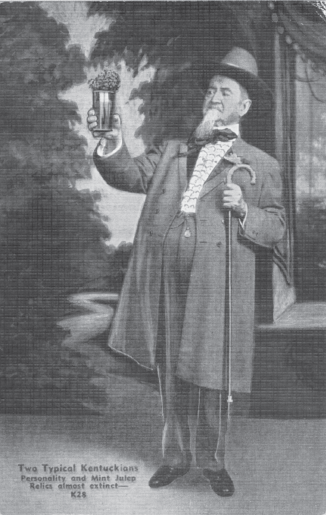

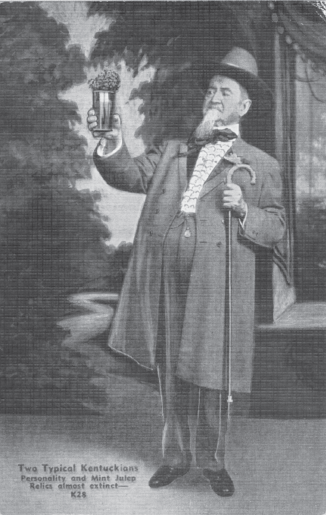

The Kentucky colonel is often associated with the traditions and history of Thoroughbred racing in Kentucky. (1917 postcard from the authors collection.)

Introduction

K entucky, racehorses, and Southern colonels just seem to go together naturally. Whether picturing Bluegrass horse farms or their close relative, the Kentucky Derby, many of us cannot summon one of those images without calling up all three. The goateed colonel holds the dominant position in the landscape of imagination that defines this central portion of Kentucky. Place the colonel on the colonnaded plaza of a grand mansion, surround him with guests and family sipping juleps served on silver trays, indulge him in his telling of tall tales about fast horses, and the image evokes Kentucky horse country.

This picture has been stamped so indelibly on notions of Bluegrass Thoroughbred culture that not even Kentuckians seem aware that horse country did not historically fit this image. To borrow a phrase from Michael Kammen, who argues that memory is reconstructed as history, the mystic chords of memory have failed to serve Bluegrass history in any faithful way. True, the mineral-rich soil, water, and bluegrass, the latter known scientifically as Poa pratensis, did spawn a significant racehorse business during the antebellum period. However, this business as it stood in Kentucky rocked precariously on the edge of decline during the first forty or fifty postbellum years. True, Thoroughbred horse racing experienced an explosive growth in popularity during this era. However, at the same time, Kentucky lost its dominant position as the locus for the breeding of racehorses. Modern new farms were arising in New Jersey and New York, fragmenting the business among multiple states.

Many are unaware that, for decades, Kentucky horsemen engaged in a power struggle with the new money in the sportthose industrialists and capitalists of New York who were spending money at unprecedented levels to develop horse farms in the Northeast. The architecture and design of these new horse-breeding operations in New Jersey and New York outshone anything existent in Kentucky, even the famed Woodburn Farm. The latter, a premier breeding operation located in Woodford County and known throughout the United States even before the Civil War, stood the leading stallions in the United States at stud. However, Woodburn Farm could not boast of the fancy appointments of these nouveau racehorse operations rising in the Northeast. The agricultural wealth of Kentuckians simply could not compete with the vast array of industrial wealth in the Northeast. Only one among Kentuckys horse breeders, Robert Aitcheson Alexander, who owned Woodburn Farm, possessed a fortune founded in industry. The numerous industrialists from the Northeast who were getting into the sport outnumbered him. And it was to the Northeast that the center of the sport had swung, with the new men of the turf breeding their own mares to their own stallions far removed from traditional horse country.

Permanent loss of this business would have affected the Bluegrass region in myriad ways, beginning with the physical landscape that has become iconic to horse country; this iconography helps draw tourism and other business. The physical landscape that marks central Kentucky as horse country includes the multitude of manicured farms, such as Calumet, that exist close to the city and can be seen without having to travel too far from downtown Lexington. The regional iconography extends to the miles of board fences signifying horses, the architecturally astounding horse barns, and the emerald-green pastures populated with bloodstock that is valued in the multimillions of dollars. As for the economic impact, earnings from horse farms ripple through the regional and state economy in numerous directions, ranging from veterinary services and hay and feed suppliers to grocery stores, office supply companies, automobile dealerships, insurance companies, and shopping malls, bringing a better lifestyle to residents regardless of whether they are directly involved in the horse economy. If the story behind the making of Kentuckys horse business provides a usable past, it is the cautionary tale of how integral this business remains to the states economyand how, without protection, it could easily be snatched away by other states eager to grab the wealth.

The overarching theme behind this struggle to build a Kentucky horse industry was the realization among the regions horsemen that they could not begin to do so without luring the big money from outside capitalists into central Kentucky. And it is my contention in this book that the money began to flow into Bluegrass Kentucky only after both locals and outsiders embraced a popular plantation myth that gave the region a neo-Southern identity. Ironically, this occurred some thirty-five to forty years after the end of the Civil War and the disappearance of the Old South. Bluegrass Kentuckys new identity had fortunate economic consequences, as it negated the regions notorious reputation for violence and lawlessness, thus bringing business to horse country. But, at the same time, this altered identity excluded African Americans from participation in the new horse industry. The new identity also rewrote the regions history, for it ignored the role the commonwealth had played as a loyal part of the United States during the Civil War. A mistaken notion grew that Kentucky had remained neutral throughout the war.