CHAPTER 1

THE GREAT WAR BEGINS

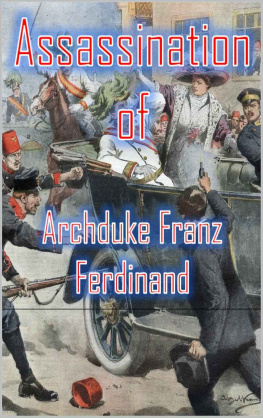

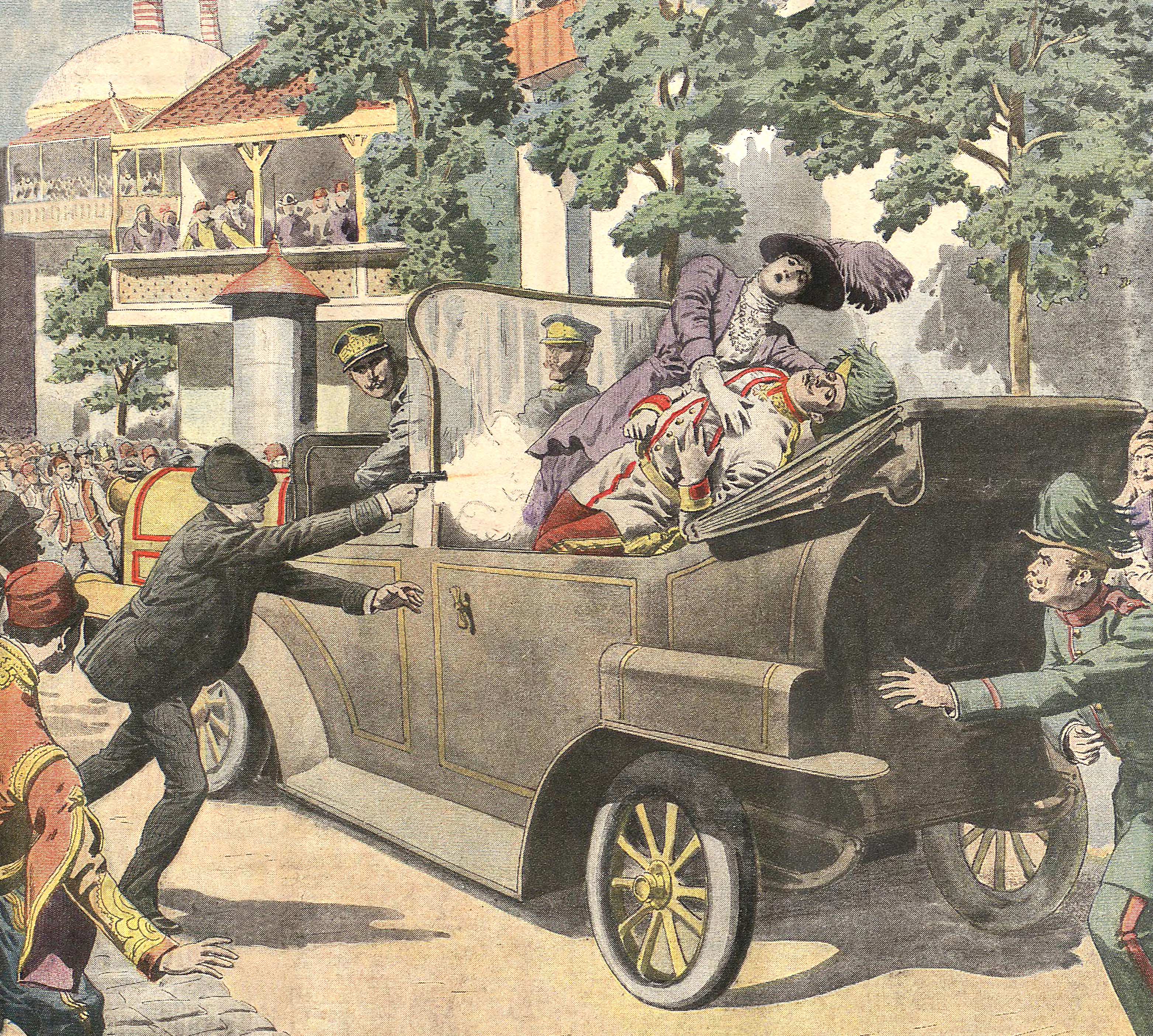

I n his office in London, Sir Edward Grey opened the first of several telegrams that would soon shock the world. It was June 28, 1914. Grey was the foreign secretary of Great Britain. He read the news that Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who was next in line to rule the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had been shot and killed in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Grey knew that the assassination could lead to a huge conflictfor Britain and the rest of the world.

The killer, Gavrilo Princip, was a Bosnian Serb with close ties to the military of Serbia. He supported Serbias desire that Bosnia and Herzegovina become independent from Austria-Hungary. Russias leader, Tsar Nicholas II, supported Serbia in its aim to weaken Austria-Hungary in that part of Europe, known as the Balkans.

A 1914 Paris newspaper illustration depicts Gavrilo Princip firing the fatal shots.

Britain had long tried to remain independent from the other major European powers. It focused more on building an overseas empire. But since the 1870s, nations with shared interests had formed alliances. Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Germany created one of these alliances. France and Russia, worried about the growing economic and military strength of Germany, formed another. Great Britain joined France and Russia in 1907 to create the Triple Entente.

For weeks after the assassination, Grey and other leaders in Europe waited to see if Austria-Hungary would respond with a military strike. They worried such an attack could spark a much larger war.

Austria-Hungary sent a list of 12 demands to the Serbian government on July 23. The Serbs accepted all but twodemands that would virtually end their independence and give Austria-Hungary control over their affairs. The Serbs then reached out to Russia, which promised to help them fight a war. Germany had already promised Austria-Hungary it would enter the war if Russia did.

Three days later Grey tried to organize a conference of European ambassadors to stop the threat of a large-scale war. The idea went nowhere. Grey told a German official that if war began, it will be the greatest catastrophe that the world has ever seen.

Austria-Hungary fired on Serbia on July 29. They were the first shots of what would come to be called the Great War. Soon the fighting spread north, as German troops moved through Belgium and Luxembourg on their way to France.

ANGER IN THE BALKANS

In October 1908 Austria-Hungary upset people around the world by annexing the small Balkan province of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The move sparked anger and protest from many Bosnians. People in the neighboring nation of Serbia were also outraged. Serbians dreamed of a united Slavic nation that included Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and other nations in the Balkans.

Belgium and Luxembourg were neutral, although both had good relations with Britain and France. The British had promised to help defend Belgium if Germany attacked. On August 4 Great Britain declared war on Germany, and eight days later it declared war on Austria-Hungary. Joining the British were its dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa and its colonies. The British said they were fighting to protect independence and other values that were vital to the civilized world. Britain also wanted to keep Germanys power under control.

Belgian soldiers march to war in 1914.

Germany and Austria-Hungary would later get help from Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire, which was based in what is now Turkey. Germany was the main military power of this group, called the Central Powers.

In the Triple Entente, Russia and France had the largest armies, while Britain had a powerful navy. Soon after declaring war, Britain sent a small land force to help France fight the Germans. Several million more troops would follow in the months and years to come. But in the first weeks of the war, the French and Belgians did most of the fighting against Germany.

For the French, the war was about defending itself from a German attack. But France also wanted to regain Alsace-Lorraine, a region to its northeast it had lost to Germany after an earlier war. France counted heavily on Russias help. Together with Great Britain, France and Russia were now known as the Allies.

THE TWO FRONTS

France attacked the Germans in Alsace-Lorraine, but most of the heavy fighting took place farther north in France and Belgium. The British Armys first major action took place at Mons, Belgium, in August. Despite being outnumbered more than two to one, the British fought so well that the German commander thought they were using machine guns instead of rifles. But the larger German forces gained the upper hand and forced the British to retreat. German troops then continued their advance on Paris, the capital of France. By September French casualties were more than 260,000. Along the Marne River, the Allies stopped the invading enemy, who began to retreat September 9. Several thousand French reinforcements had piled into 600 taxicabs in Paris to reach the battle.

In October some of the heaviest fighting took place near the Belgian city of Ypres. The Germans managed to take some land, but the Allies remained in the region. They were determined to keep all the territory they held, even though they were paying a high cost in casualties.

Russias army was the worlds largest with 1.4 million troops, but it had trouble against the Central Powers. The Russians had had some success in Galicia, which was part of Austria-Hungary. But they had then suffered a major defeat against the Germans at the Battle of Tannenberg at the end of August. Over the next several months, the Russians continued to fight with no major victories. As 1914 ended the Allies realized they faced a long war against a determined enemy.

CHAPTER 2

YEARS OF DESTRUCTION

T roops moved freely across the battlefield in the wars early months. But by 1915 the war centered on trenches on the Western Front, a line stretching more than 450 miles (725 kilometers) across northern France between the Swiss border and the North Sea. The men lived in the trenches and used them for protection from enemy attacks. The land between Allied trenches and the enemys was known as no mans land. British trenches were about 7 feet (2 meters) deep and 6 feet (1.8 m) wide, although the sizes varied. As fighting moved from one area to another, the soldiers built more connecting trenches, creating complicated mazes.

British soldier Arthur Maitland wrote his parents that he stayed in the trenches almost all the time. The Germans shell us constantly but we laugh at them from our burrows like rabbits. But a fellow soldier, Neville Woodroffe, wrote home about the huge number of deaths he saw and said, This is a terrible war. He was killed a month later.

An abandoned British trench, which was captured by the Germans

Even as the Allies tried to kill the Germans, the two sides did at times realize their enemies were human. In December 1914 British and German soldiers in parts of France and Belgium shared what was called the Christmas truce. They stopped fighting for the holiday. They sang Christmas carols, and German soldiers set up Christmas trees. Enemy troops even came out of the trenches to shake hands with each other. But after Christmas was over, the soldiers once again returned to the war, determined to beat their enemies.