THE WAR THAT ENDED PEACE

MARGARET MACMILLAN is the author of Women of the Raj and international bestsellers Nixon and Mao and Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War, which won the 2002 Samuel Johnson Prize. Her most recent book is The Uses and Abuses of History [978 1 84668 210 0], also published by Profile. The past Provost of Trinity College at the University of Toronto, she is now the Warden of St Antonys College and a Professor of International History at Oxford University.

Also by Margaret MacMillan

WOMEN OF THE RAJ

SEIZE THE HOUR: WHEN NIXON MET MAO

PEACEMAKERS: THE PARIS CONFERENCE OF 1919 AND ITS ATTEMPT TO END WAR

USES AND ABUSES OF HISTORY

EXTRAORDINARY CANADIANS: STEPHEN LEACOCK

THE WAR THAT ENDED PEACE

How Europe Abandoned Peace for the First World War

Margaret MacMillan

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

This eBook edition published in 2013

Copyright Margaret MacMillan

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 416 8

To my mother Eluned MacMillan

Contents

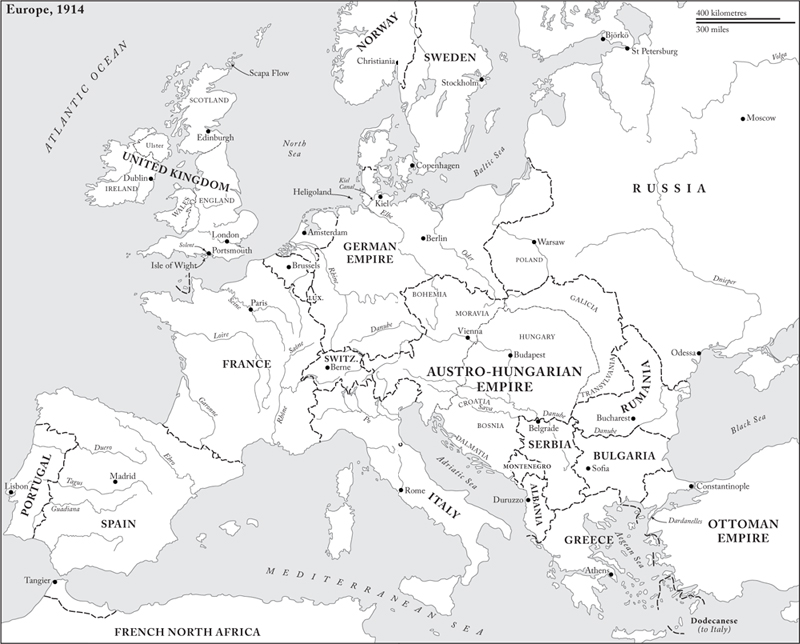

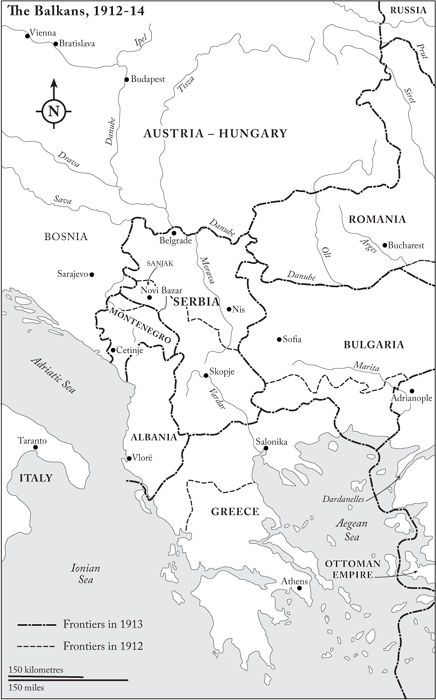

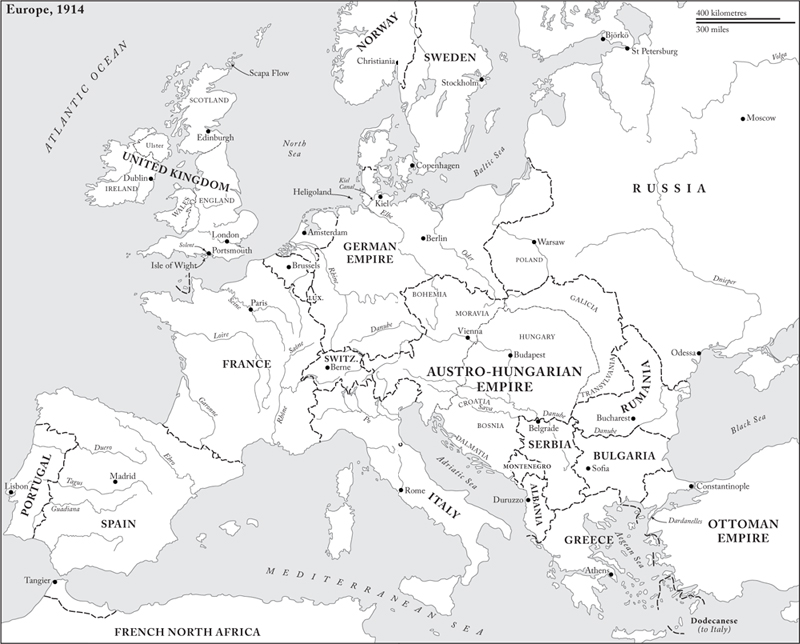

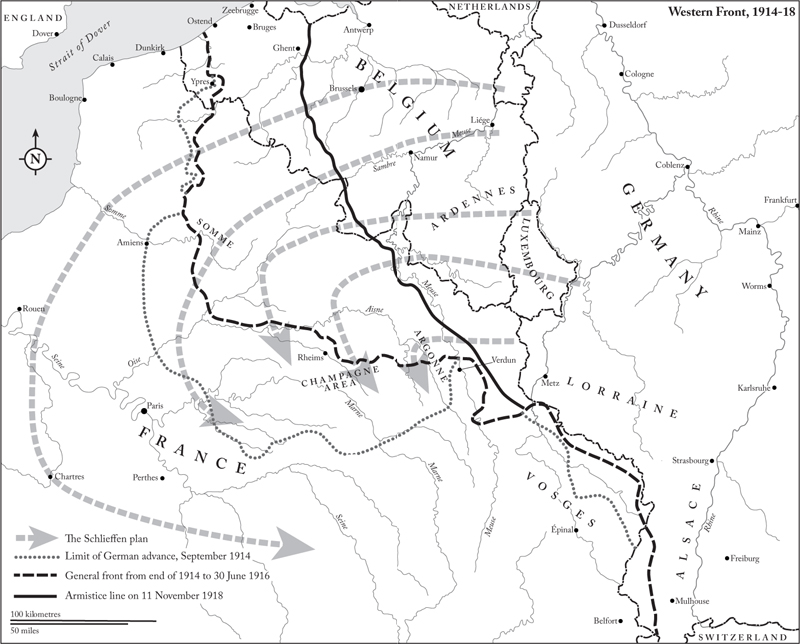

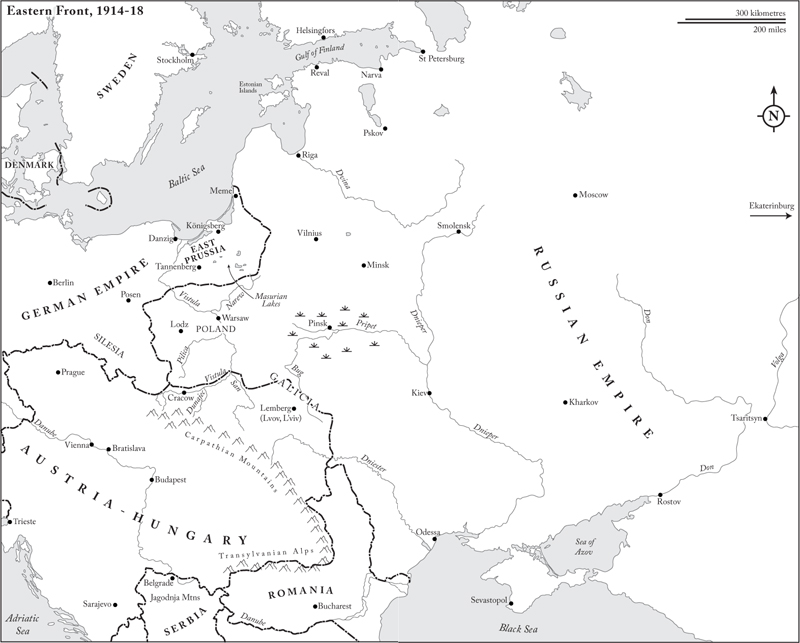

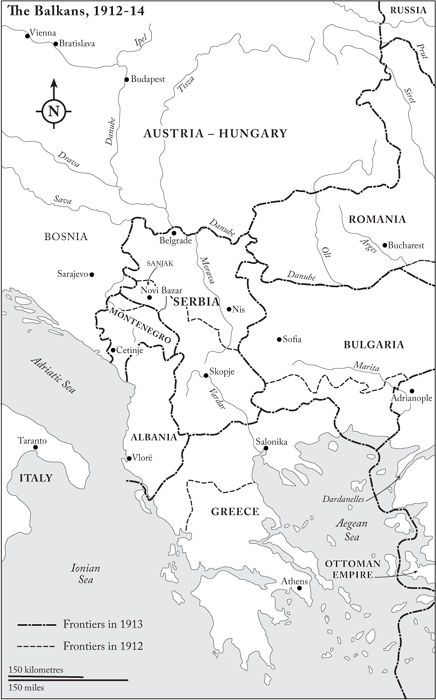

Maps

Introduction: War or Peace?

There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always wars and plagues take people equally by surprise.

Albert Camus, The Plague

Nothing that ever happened, nothing that was ever even willed, planned or envisaged, could seem irrelevant. War is not an accident: it is an outcome.

One cannot look back too far to ask, of what?

Elizabeth Bowen, Bowens Court

Louvain was a dull place, said a guidebook in 1910, but when the time came it made a spectacular fire. None of its inhabitants could have expected such a fate for their beautiful and civilised little town. Prosperous and peaceful over many centuries, it was known for its collection of wonderful churches, ancient houses, a superb Gothic town hall and a famous university which had been founded in 1425. The university library, in the distinguished old Cloth Hall, held some 200,000 books including many great works of theology and classics as well as a rich collection of manuscripts which ranged from a little collection of songs written down by a monk in the ninth century to illuminated manuscripts over which the monks had toiled for years. In late August 1914, however, as the smell of smoke filled the air, the flames that destroyed Louvain could be seen from miles away. Much of the town, including its great library, went while its desperate inhabitants, in scenes that would become all too familiar to the twentieth-century world, struggled out into the countryside carrying what belongings they could.

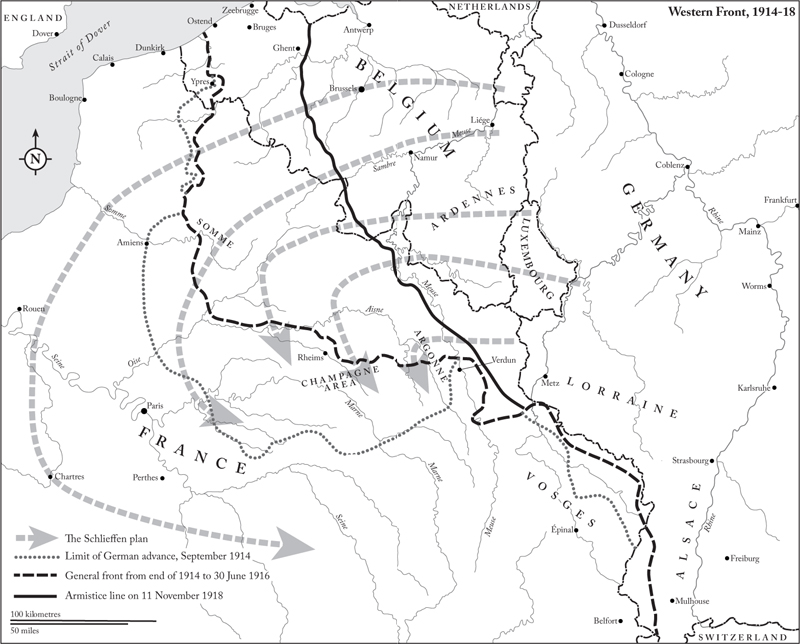

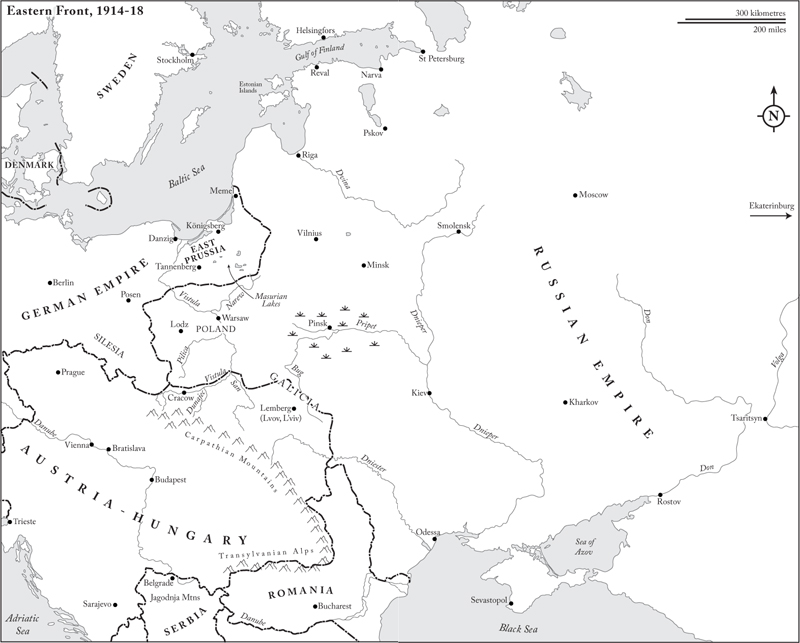

Like much of Belgium, Louvain had the misfortune to be on the route of the German invasion of France in the Great War that broke out in the summer of 1914 and which was to last until 11 November 1918. The German war plans called for a two-front war with a holding action against Russia, the enemy in the east, and a rapid invasion and defeat of France in the west. Belgium, a neutral country, was meant to acquiesce quietly as German troops marched through on their way southwards. As with so much of what later happened in the Great War, those assumptions turned out to be very wrong. The Belgian government decided to resist, which immediately threw the German plans out, and the British, after some hesitation, entered the war against Germany. By the time the German troops arrived in Louvain on 19 August they were already resentful at what they saw as an unreasonable Belgian resistance and they were nervous about being attacked by Belgian and British troops as well as by ordinary civilians who might decide to take up arms.

For the first few days all went well: the Germans behaved correctly and the citizens of Louvain were too afraid to show any hostility to the invaders. On 25 August new German troops arrived, retreating from a Belgian counter-attack, and rumours spread that the British were coming. Shots were fired, most likely by the nervous and perhaps drunken German soldiers. Panic mounted among the Germans, who were convinced that they were under attack, and the first of the reprisals started. That night and in the next days civilians were dragged out of their houses and a number, including the mayor, the head of the university, and several police officers, were shot out of hand. By the end some 250 out of a population of around 10,000 were dead and many more had been beaten up and insulted. Fifteen hundred inhabitants of Louvain, from babies to grandparents, were put on a train and sent to Germany where the crowds greeted them with taunts and insults.

The German soldiers and their officers frequently joined in sacked the town, looting and pillaging and deliberately setting buildings on fire. Eleven hundred of Louvains 9,000 houses were destroyed. A fifteenth-century church went up in flames and its roof caved in. Around midnight on 25 August, German soldiers went into the library

This was only the start as Europe laid waste to itself in the Great War. The 700-year-old Rheims Cathedral, the most beautiful and important of the French cathedrals and where most French kings had been crowned, was pulverised by German guns shortly after the sack of Louvain. The head of one of its magnificent sculptured angels was found lying on the ground, its beatific smile still intact. Ypres, with its own superb Cloth Hall, was reduced to rubble and the heart of Treviso in the north of Italy destroyed by bombs. Much although by no means all of the destruction came at the hands of Germans, something which had a profound impact on American opinion and which helped to propel the United States towards entering the war in 1917. As a German professor said ruefully at the wars end: Today we may say that the three names Louvain, Rheims, Lusitania, in almost equal measure have wiped out sympathy with Germany in America.

Louvains losses were small indeed by what was to come the more than 9 million soldiers dead and another 15 million wounded or the devastation of much of the rest of Belgium, the north of France, Serbia or parts of the Russian and Austrian-Hungarian Empires. Yet Louvain came to be a symbol of the senseless destruction, the damage inflicted by Europeans themselves on what had been the most prosperous and powerful part of the world, and the irrational and uncontrollable hatreds between peoples who had so much in common.

Next page