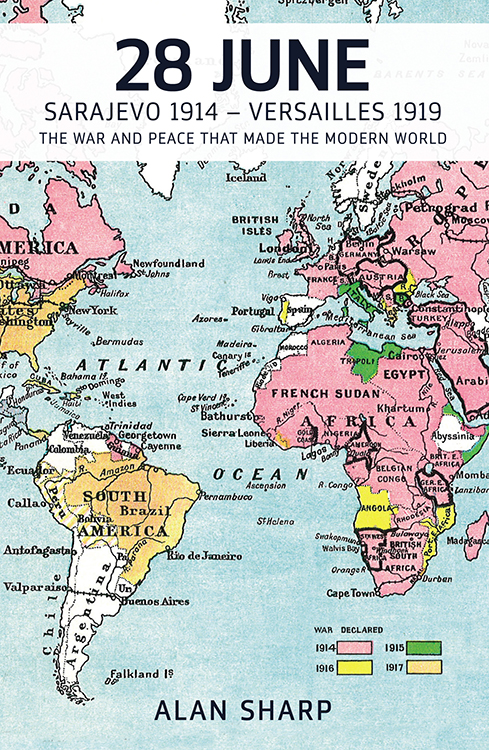

28 June

Sarajevo 1914Versailles 1919

The War and Peace that Made the Modern World

Edited by Alan Sharp

For Jamie and Chloe

Contents

Acknowledgements

Map 1: Europe 1914

28 June 1914: Assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo

28 July 1914: Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia

1 August 1914: Germany declares war on Russia part I

1 August 1914: Germany declares war on Russia part II

3 August 1914: Germany declares war on France

4 August 1914: Germany invades Belgium

4 August 1914: Britain (and its empire) declare war on Germany part I

4 August 1914: Britain (and its empire) declare war on Germany part II

Map 2: Western Pacific Rim

23 August 1914: Japan declares war on Germany

1 November 1914: Russia declares war on Turkey

Map 3: The Ottoman Empire 1914

23 May 1915: Italy declares war on Austria-Hungary

14 October 1915: Bulgaria declares war on Serbia

Map 4: Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria 191223

9 March 1916: Germany declares war on Portugal

5 June 1916: Arab revolt against the Ottomans begins

Map 5: The Arab Revolt and its aftermath

30 August 1916: Turkey declares war on Romania

6 April 1917: United States Congress declares war on Germany

7 April 1917: Cuba and Panama declare war on Germany

13 April to 7 December 1917: South America and the First World War

27 June 1917: Greece declares war on Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and Turkey

22 July 1917: Siam declares war on Austria-Hungary and Germany

14 August 1917: China declares war on Austria-Hungary and Germany

26 October 1917: Brazil declares war on Germany

12 January 1918: Liberia joins the war

5 November 1918: Poland declares Independence

28 June 1919: The Treaty of Versailles part I

28 June 1919: The Treaty of Versailles part II

Map 6: Europe 1923

Map 7: Turkey and the Near East 1923

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the contributors to this volume for making the editors task so straightforward. Since many of them are friends and colleagues from our earlier Makers of the Modern World series it has been a particular pleasure to resume our collaboration. Chapters have arrived on time and any requests for adjustments have been met with unfailing courtesy and cooperation. Jaqueline Mitchell, who manages to combine quiet efficiency with sensitivity for her authors, is the most sympathetic of commissioning editors. Colleagues at Haus have advanced this venture with their usual friendly and effective manner, with particular thanks due to Ellie Shillito and Aran Byrne. Professors Tom Fraser, Tony Lentin and Sally Marks, together with Baroness Ruth Henig, have been, as ever, enormously supportive and generous with their encouragement, comments and suggestions.

When our publisher, Dr Barbara Schwepcke, asked me to edit the Makers series I envisaged it as an appropriate final project before I retired. This was clearly not her intention and I have been kept busy ever since, for which I am on most days suitably appreciative. Her vision and support remain inspirational and her friendship has brought a unique flavour to our various endeavours. As always my principal debt is to my wife Jen who creates the calm, space and stability which remains the foundation of everything. This book offers her some proof, I hope, that not all my time on my computer is spent playing bridge.

Alan Sharp

University of Ulster

Introduction

Alan Sharp

On Sunday 28 June 1914 Gavrilo Princip, a young Bosnian Serb, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo in Bosnia. Thirty-seven days later Europe was at war. Although as recently as May 1914 Sir Arthur Nicolson, the Permanent Under-Secretary of the British Foreign Office, had written Since I have been at the Foreign Office, I have not seen such calm waters, a tsunami was about to overwhelm Europe.

On Saturday 28 June 1919, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles in France, representatives of Germany and 30 Allied and Associated Powers signed the treaty re-establishing peace between them. Although neither literally the beginning nor the end of the First World War, 28 June symbolically marks the parameters of the worlds most costly conflict to that date. Its economic, political and international effects were seismic, making it the single most important event of the 20th century. How had it come about?

In 1898 the British Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, in words redolent of the social Darwinism then in vogue, had suggested that the international balance of power was changing: You may roughly divide the nations of all the world as the living and the dying the weak states are becoming weaker and the strong states are becoming stronger the living nations will gradually encroach on the territory of the dying and the seeds of conflict among civilised nations will appear. Demographic and economic developments offered some clues as to which states might prosper or decline, with population and coal and steel production figures as crude indices of power. States abilities to maintain their inner cohesion in the face of the problems created by industrialisation, urbanisation and the growth of new ideological challenges from liberalism, socialism and democratisation also provided important indications of their capabilities. Nationalism, and the aspirations of subject national minorities, posed a particular problem for the multi-national autocracies of Russia and, especially, Austria-Hungary. The key question was whether the international system could cope with these challenges without, as Salisbury feared, resort to war.

In addition to changes in the relative strengths of the European states, the emergence of new powers such as the United States and Japan complicated the international scene. Rapid and expensive technological innovation, coupled with a growing number of naval powers, challenged the supremacy of Britains Royal Navy, the main arm of its defence. European conscript armies were increasing in size, with greater killing power. Nonetheless, the division of Africa and the subsequent competition for concessions in China were resolved without conflict in the 1880s and 1890s. Both offered, however, examples of a perceived need to secure gains in the present in the face of pessimism about an uncertain future a trait which had a major role to play in the thinking of several states in 1914. Germany, by 1914 an urbanised industrial giant, rich in steel, coal, chemical and electrical industries, and with a well-educated population of 66 million, seemed secure. Yet Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the Chancellor, refused to plant trees on his Prussian estate, predicting that the Russians would occupy it within 30 years.

Europe experienced a number of crises in the new century, each of which was resolved peacefully, perhaps contributing to complacency amongst decision-makers that this would always be the case. France and Germany clashed twice over Morocco in 1905 and 1911, each time leaving Germany feeling humiliated despite its apparent success in obtaining recognition of its right to be consulted and compensated. Austria-Hungarys annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 ended the period of Austro-Russian dtente in the Balkans, leaving Russia embarrassed and with a grievance. Russia was embarrassed because its abandonment of Serbias ambitions in the two provinces, for the promise of Austrian support for Russian control of the Straits, had exposed the hollowness of its claim to be the protector of Slav interests. Its grievance arose because Austria reneged on its promise, subsequently relying on Germany to face down an indignant Russia. Such legacies of perceived failure limited actors options in future confrontations, causing them to lose confidence in compromise solutions.