Published in 2018 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW 11 3 TW

Previous editions were published in 2010 and 2015

Copyright Alan Sharp, 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-912208-09-8

eISBN: 978-1-912208-12-8

Maps created by Martin Lubikowski

Typeset in Sabon by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in Spain by Liberdplex

All rights reserved.

Introduction

There is no single person in this room who is not disappointed with the terms we have drafted.

Lord Robert Cecil, Paris, 30 May 1919

The peace treaties signed in various Parisian palaces and suburbs at the end of the First World War have not enjoyed a sparkling reputation. In the words of Jan Christian Smuts, the South African delegate and close colleague of the British premier at the time, David Lloyd George, such a chance comes but once in a whole era of history and we missed it. The prevailing perception remains that this was a huge opportunity spurned. The treaties at the end of the war to end all wars and to make the world safe for democracy delivered neither outcome. Instead they were deemed to have a large responsibility for the establishment of the dictatorships of the inter-war period and the outbreak of a second conflagration in 1939. In the post-Second World War and Cold War eras they continue to attract condemnation for their legacies in the Balkans, the Middle East, the Russian borderlands, the former European empires, in Africa and Asia and indeed worldwide, particularly in the wake of two seminal events, 11/9 (the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989) and 9/11 (the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington on 11 September 2001).

Smuts disappointment, shared by the leading Conservative politician Lord Robert Cecil who, as his colleague on the League Commission, had also played a prominent role in the drafting of the League of Nations Covenant was typical of many attending a meeting of British and American experts in May 1919. They were anxious to embody their peace conference cooperation and experience into an organisation with parallel branches in each country designed to deliver an essential aspect of US President Woodrow Wilsons brave new world a body of informed, aware and

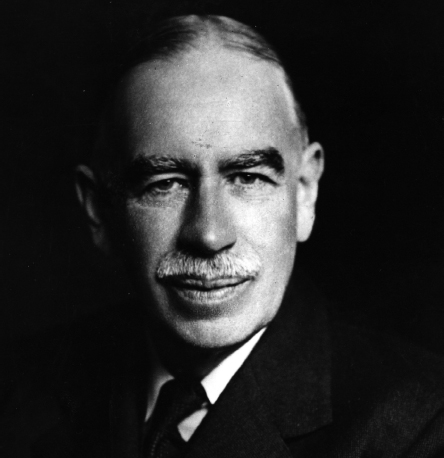

Their disquiet was emphasised and publicised by another former conference participant, John Maynard Keynes, a Treasury official who resigned from the British delegation in June 1919 to write one of the most influential polemics of the 20th century, The Economic Consequences of the Peace , published in December 1919. This stinging attack on the Allied leaders and all their work, in particular reflecting Keynes bitter disappointment with Wilson, has played a major role since in shaping the widely held perception of the settlement as a failure and a missed opportunity. Later memoirs by other conference members such as Harold Nicolson, Headlam-Morley, Stephen Bonsal and Robert Lansing did little to dispel the contemporary conclusion of a distinguished British soldier, Archibald Wavell, who served in both world wars, that after the war to end war they seem to have been pretty successful in Paris at making a Peace to end Peace. The outbreak of a second major continental war in September 1939 seemed to confirm both Wavells observation and the verdict of the French commander of the Allied forces on the Western Front, Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who allegedly declared of the Treaty, This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years.

The renewed conflict in Europe in 1939 that escalated in 1941 into a new world war, incurred costs and consequences even more far-reaching than the inconceivable losses, by contemporary standards, of the First World War. Unsurprisingly, in those circumstances, later commentators continued to endorse the contemporary condemnations of the settlement and particularly the Treaty of Versailles. The American diplomat George Kennan wrote in 1985, I think its increasingly recognised that the

Whatever the responsibility of the settlement for this new war, by 1945 Europe was a ruined continent dominated by two extra-European powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. The rapid collapse of their victorious alliance into an ideological and power struggle between two superpowers that would last for over 40 years, transformed the barrier already apparent in 1919 between eastern and western Europe into an iron curtain. The Cold War did freeze some of the persistent post-Versailles problems of the 1920s and 1930s but when first the Soviet empire, and then the Soviet Union itself collapsed, many of these issues re-emerged.

There can be little doubt that 198991 made 1919 relevant in a way that it had not been during the Cold War. The Versailles settlement is held responsible for the ethnic conflicts in Europe and Asia following the collapse of the USSR, and for the Balkan problems ensuing from the demise of Yugoslavia. In the wider world it has been blamed for its reinforcement of imperialism in Africa, Asia and Latin America and, in particular, for the nightmare of the Middle East, due to the artificial, sketchily defined states that it created, and the hopelessly conflicting promises made to Jews and Arabs during and after the First World War. In such circumstances it is not surprising that the peace settlement made at the end of that conflict has had few friends.

A plethora of published documents (carefully chosen, edited and if necessary falsified) followed, first from Germany, then from other participants. Overwhelmed by the weight of this evidence the general consensus by the mid-1930s was that the First World War was an accident for which no one power was primarily accountable. This in turn further undermined the credibility of a settlement based on the premise of German responsibility.

Perhaps surprisingly, the thesis of the accidental origins of 1914 survived the Second World War until decisively challenged by Fritz Fischer in the late 1950s and early 1960s, amidst huge controversy in his native Germany. Few would now dispute that the crucial decisions for war in 1914 were taken by Germany and its allies.

John Maynard Keynes, 1 January 1940

Keynes was entitled to his opinion, but there are alternative interpretations. Recent scholarship has tended to be more sympathetic to the peacemakers, drawing attention to the overwhelming problems that they faced and offering more rounded and nuanced accounts of the Paris peace negotiations. Many, though not all, volumes of the recent Makers of the Modern World series comprising studies of the peacemakers and their states reflect the current scholarly consensus that the settlements were flawed but probably represented the best that could have been achieved in the circumstances, and that any judgements upon them need to also consider the subsequent actions and policies of those called upon to implement the peace terms.