Acknowledgements

As well as to the many scholars who have taken on the life and multifarious writings of Woodrow Wilson, I owe an even longer-standing debt to Owen Dudley Edwards, Richard Crockatt, and Eric Homberger who were my mentors if not my formal tutors in American history and politics at the Universities of Edinburgh and East Anglia. I owe a great deal, too, to Geir Lundestad, currently director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute but a profound scholar of American civilisation, to whom I briefly and bizarrely stood as proxy at the University of Troms in 1979 while he fulfilled obligations elsewhere. It was a hugely fruitful experience, but homoeopathically cured me of any desire to be a lifelong academic.

Profound thanks to my commissioning editor Jaqueline Mitchell, who could have deployed more severe sanctions as this manuscript ran ever later but who kept channels of diplomacy open and avoided conflict. Brief thanks, too, to Gore Vidal who referred to Woodrow Wilson as idiotic during a BBC interview, and rekindled my enthusiasm at a moment when health and spirits were at a low ebb.

Ive counted, too, on the unswerving loyalty and support of my wife Sarah (whose brother Neil is in harms way with the American Marines in Iraq at the time of writing) and our son John who will be pleased to see that books about the glasses man are no longer cluttering his fathers desk. And if it doesnt make me sound too much like a Miss World contestant, this essay is dedicated to world peace, which has never seemed to me a foolish or unworthy aim.

Introduction: Dear ghosts

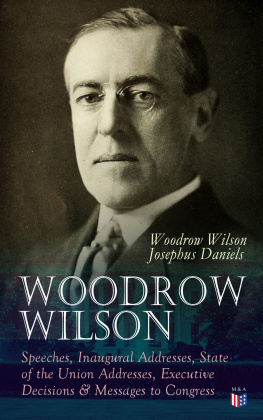

Colorado is American heartland. High, semi-arid, landlocked, tucked between the great plains and the Continental Divide that runs down the middle of the Rocky Mountains, neither North nor South the Centennial State did not join the Union until a decade after the Civil War Colorado retains a reputation for political independence, a folk-memory, perhaps, of the states previous existence as a free Territory, self-determining and relatively unorganised. On 25 September 1919, a man came to the small south-eastern Colorado city of Pueblo, trying to save an idea.

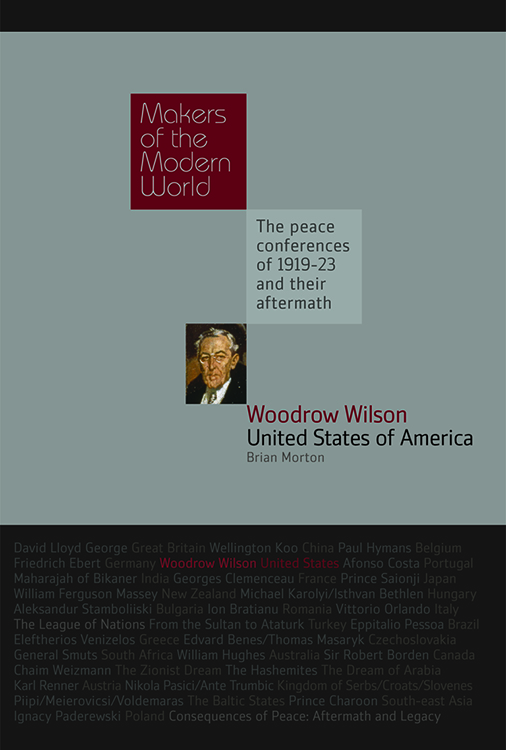

The idea in its purest form was peace, but it was typical of a man still routinely and misleadingly described as an idealist, condemned by his enemies as a nave and dangerous utopian, and still casually dismissed by history as a failure, that he should be more concerned to defend the form and practical structure of his idea than the idea itself. In Pueblo, Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States, made his last public attempt to demonstrate that these things were inseparable and inextricable, and to convince the American people to accept in undiluted and uncompromised form both the Treaty of Versailles, which had brought to an end the Great War in Europe, and a great international League of Nations as a guarantor of future peace. It is one of the great ironies of history that having expended extraordinary effort on both the treaty, of which he was a major architect, and the idea of a League his name is indissolubly linked to the latter, though the first proposal came from an English statesman and having sacrificed health and political standing at home to an insistence that they be adopted together and whole, he should repeatedly instruct his Democratic supporters in the Senate to vote against them both and deny acceptance of the Paris peace settlement and American entry into the League of Nations the two-thirds majority they needed for ratification.

The irony was widely perceived, then and since. In 1945, at the end of a second world conflict widely accepted as an inevitable extension of the first and a bloody confirmation of the misjudgements of the Paris Peace Conference and the disastrous consequences of American failure to ratify the treaty and join the League, the historian Thomas A Bailey published a book entitled Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal. The title alone gives little indication who is doing the betraying or what is being betrayed, but a line from the book jumps out: With his own sickly hands, Wilson slew his own brain child. In 1919, a satirical cartoonist had anticipated the same metaphor, depicting a sombrely clad Wilson always caricatured in clerical black rocking a stillborn infant in a tiny coffin-cradle, while the British and French prime ministers David Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau, fellow-architects of the Treaty, lurk ambiguously in the background.

Successive waves of revisionist historiography since his death in 1924 have attempted to vilify or rehabilitate Wilson, in terms that are either politically crude or psychologically hyper-subtle. Born in the same year as Sigmund Freud, it was Wilsons ambiguous fate to be the first living political leader to be profiled (albeit at a distance) by the founder of psychoanalysis, in collusion with William C Bullitt, a Wilson aide at the Peace Conference who resigned over what he considered the severity of the terms being imposed on Germany. Some part of that is due to a remarkable and often overlooked foreshortening of the chronology. Wilson spent only nine years in national politics and only three on an international stage, and if his career seems given over to the promulgation of one Big Idea, that idea and the apparatus that came with it only occupied him for a tiny proportion of a life that very nearly reached its biblical span. To be sure, his actions and in almost equal measure his refusals to act during the period are of incalculable significance, but to concentrate on them entirely is to lose a vital context.

In the same way, to concentrate on Wilsons health and psychology, both of which have been analysed in unprecedented detail, is to miss a point as well. His background as a Presbyterian son of the manse was an important shaping influence on his subsequent career, but the specific nature of that influence remains unclear, as does the impact of his mothers hypochondriasis, which he seems to have inherited. Some have seen this emerging even in his speeches, where health of the nation, of the individual, of democracy is a recurring metaphor, and the metaphor in turn reinforces the image of Wilson as an unworldly valetudinarian. It is clear that he suffered significant, and by no means psychosomatic, illness throughout his life, and that his digestive ailments and series of small but successively disabling strokes did occasionally affect his judgement and ability to function on occasions. Equally, it is clear that specific emotional crises notably the death of his first wife and engagement to his second coincided with and in some way coloured his reaction to major events: as Europe slid into the war that now seems to define Wilsons political life, Ellen Axson Wilson was dying of Brights disease; bracketing the critical period that saw the sinking of the Falaba, the Lusitania and the Arabic and the loss of 177 American lives to German torpedoes was Wilsons courtship of and eventual acceptance by Edith Bolling Galt. Though Wilson had a remarkable ability when required to bleach his public presentation of any purely private emotion it was a more reticent time, in any case there can be no doubt that these events changed his behaviour at the time.

However, as with any easy generalisation about Wilson, his obsession with health is a backwards extrapolation from the knowledge that he suffered from several real ailments as well as imaginary ones, and to that extent is more apparent than actual. His health problems in young manhood may point to episodes of nervous prostration or to an early onset of hypertension, and the professorial or clerical figure Wilson cut in later years, with prominent false teeth and small eyeglasses did not suggest a man of action. On the other hand, Wilson was an enthusiastic baseball fan who had played centre field while at Davidson College in North Carolina and helped manage the varsity team at Princeton, though he was unable to win a playing place there. He became the first president officially to throw out the first ball at the World Series. The Wilsons had taken walking and cycling holidays in the Lake District and when the presidency restricted his physical freedom, he became an enthusiastic, if high-handicap, golfer; there is even a story that Secret Service agents painted some of his golf balls black so that he could play in snow in the White House grounds. Wilson may even have been addicted to exercise, a condition which affects many fit men and women who are subsequently pushed into sedentary lifestyles. When he was unable to take brisk walks, Wilson seems to have suffered non-specific ailments. In Paris, when he was locked in long and arduous negotiation over the shape and direction of the post-war world, his doctor and fellow-delegates forced him to exercise in front of an open window merely in order to get back some natural colour and appearance of vitality. He enjoyed fast cars, particularly convertibles, and liked the company of women; his libido seems to have been perfectly normal he and Ellen Wilson had three daughters in four years. Despite Freuds and Bullitts attempt to construct an Oedipal pathology, there seems to have been little abnormal in Wilsons family relationships, though he did continue to depend to an unusual, if not aberrant, extent on the close loyalty of his wife, secretary and a few political friends rather an extended circle. Nothing that points to a weakly or unduly neurotic personality, and indeed Clemenceau compared him favourably in terms of determination and stubbornness to General Pershing, commander of the American forces in Europe. Perverse though it inevitably sounds, no one fought more fiercely for peace than Woodrow Wilson, abandoning his principle of peace without victory almost as soon as the US entered the war, leaving its prosecution entirely to the generals (a situation unique in modern American history), and conducting his foreign policy with a belligerence that puzzled his future associates in battle (Britain and France were never formal US allies, as in the Second World War) and so alarmed the near-pacifist William Jennings Bryan that he resigned as Secretary of State.