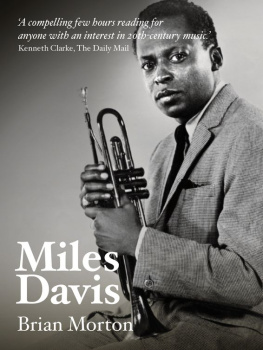

Miles Davis (1926-91) was one of the great jazz musicians, bandleaders and composers. His recordings include several of the most acclaimed and popular jazz albums, from the relaxed style of Birth of the Cool to the orchestral Sketches of Spain and the iconic Kind of Blue. And he never ceased to innovate. As the 1960s moved into the 1970s, he developed a darker, more complex sound and began increasingly to use electric instruments. The crowning achievement of his experiments, Bitches Brew (1969), became the bestselling jazz album of all time. In this biography, noted jazz critic Brian Morton takes us through the musical history of this remarkable and influential artist and illuminates the personality behind the sound.

There is a special class of artists for whom there exist no terms of critical reference larger than those articulated in the work itself, or in the artists writings about it. Pablo Picasso is an obvious example, seemingly omnicompetent, and in every form and style from the naturalistic to the abstract. So is Karlheinz Stockhausen, creator of a vast operatic cosmology and a proportionately huge body of texts and interviews explaining its procedures and significance. So, in their very different ways, are three Americans.

Norman Mailers career as novelist, essayist, film-maker, poet, gadfly and sensationalist is pulled together by a strange Manichean metaphysics largely of his own devising. If Mailer is the epitome of the performing self, Andy Warhol seemed to negate every last shred of personality in art often casually consigning work to others and yet it is now virtually impossible to see any of the three defining forces of the modern world the fetishised news image, advertising, celebrity other than through his pale, photophobic eyes. And then there is John Cage, arguably one of the most important artistic catalysts of the 20th century, notorious for making silence not just a dramatic device in music, but the substance of music itself. How to explain Cages work, or that of any of the others, in terms more expansive than his own?

At first glance, a jazz trumpeter does not seem to belong in this company, but the career of Miles Davis offers curious parallels with them all. To be sure, he never articulated any coherent philosophy, made few coherent statements about his work, and not a few misleading ones, and even rejected the terminology of jazz itself. And yet Miless silences are as evocative as Cages, whether the silences that greeted callow questions about his aesthetic or the silences he built into music.

Like Warhol, Miles was often content to leave aspects of his creation to other hands, relying on other composers within his groups, leaning heavily on the arranging skills of Gil Evans, Paul Buckmaster and Marcus Miller, and during his most creative period handing over an unusual degree of musical responsibility to his producer and engineer Teo Macero. Like Warhol in his youth, Miles in later life became an obsessive doodler and sketcher, leaving behind a body of artwork that acquired a substantial posthumous reputation. When no less a figure than Jack Lang, the French culture minister dubbed him the Picasso of jazz he was thinking less of Miless graphic skills than the sheer richness of his musical creativity which seemed to take a new direction with every passing year and every new record, embracing virtually every jazz form from the blues to abstraction, from the headlong virtuosity of bebop to the deceptive simplicity of contemporary pop. It took him into other areas as well. At the beginning of the 1970s new decades almost invariably sparked new creative initiatives from Miles he was listening closely to the music of Stockhausen, fascinated by chance similarities between his own bandleading philosophy and the German composers intuitive approach, between Stockhausen s ambitious use of electronics and his own attempt to bring to jazz some of the furious electric energy of rock, funk and soul.

As to Norman Mailer, he inadvertently provided the keynote to Miless creative life when he described his own ambition to catch the Prince of Truth in the act of switching a style. Like Miles, Mailer has never been afraid of confrontation, with others and with his own shortcomings. He has taken huge creative risks, dared to write in the crudest popular form and with impenetrable obscurity. He is almost as well known for his marriages and love affairs as for his writing, a media obsession that, however understandable, has hampered appreciation of his work as much as a parallel obsession with Miless personal style hampered understanding of his music. Unlike Miles, Mailer has aired his political views in public. Indeed, he has developed a vast philosophical or cosmological system involving God and the Devil in perpetual conflict , existential violence, mysticism, cancer and a creeping plague at the heart of modern life. However far-fetched it may sound, Miles played a small part in the creation of that mythos. Mailers notorious essay The White Negro, his manifesto for the hipster-outsider who might shake the grey consensus of 1950s, was largely inspired by the fierce, separatist aesthetic of the beboppers.

There was also a personal connection between Miles and Norman Mailer. Aware that his (fourth) wife Beverly Bentley had a relationship with Miles, possibly ongoing, Mailer put a version of him in a novel. Published in 1965, AnAmerican Dream is not just written in an edgy new style, but was produced in a risky new way, familiar to Charles Dickens but unthinkable in 20th century publishing , with each chapter published in a magazine before the next was written, offering no chance to correct false narrative trails. Theres an obvious parallel with the new recording methods Miles was to pioneer later in the decade. His identity is disguised in that Shago Martin is a singer, not a trumpet player, but there is no mistaking the source. At the publication party, Miles came over and caressed Beverlys hair. There was an angry stand-off, two small pugilistic men with reputations and sexual egos out of all proportion to their actual stature. It was Norman Mailer who eventually backed down In life, and in afterlife, Miles Davis answers to no logic but his own.

What follows is a plain narrative of a creative life. One hears very little in it from Miles himself because he left few published writings beyond laconic liner notes for records and because his Autobiography, ghost-written by poet Quincy Troupe, is as notoriously unreliable as Billie Holidays Lady Sings the Blues. Over the years, I have spoken to many of those who worked with Miles, including drummer Jimmy Cobb, saxophonist Kenny Garrett, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Dave Holland, pianist Keith Jarrett, guitarist John McLaughlin, bassist Marcus Miller, keyboard player Joe Zawinul. I have chosen to quote from those interviews very sparingly indeed. Everyone who has ever worked with Miles remembers him with a curious mixture of deep affection and deeper ambivalence . Interviewees rarely give more than anecdotal impression of his working methods, and those stories are available elsewhere. By and large, their comments are aimed at redressing one or another misconception about Miless character. He emerges here through his public actions rather than the words of others, and emerges as a flawed, complex individual with the ability of a perverse chameleon to change his temperamental colouration so that it failed to fit the mood of a given situation. If someone complimented or praised Miles, as conductor Quincy Jones did on Miless farewell, retrospective night at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1991, they were treated to his signature F*** you. If someone challenged him, or persisted in their own stance and individuality, they were treated with warmth and respect.