THE STUDIO RECORDINGS OF THE MILES

DAVIS QUINTET, 196568

OXFORD STUDIES IN RECORDED JAZZ

Series Editor JEREMY BARHAM

Louis Armstrongs Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings

Brian Harker

The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 196568

Keith Waters

THE STUDIO

RECORDINGS OF

THE MILES DAVIS

QUINTET, 196568

KEITH WATERS

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

with offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Waters, Keith, 1958

The studio recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 196568 / Keith Waters.

p. cm.(Oxford studies in recorded jazz)

Includes bibliographical references, discography, and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-539383-5; 978-0-19-539384-2 (pbk.)

1. Davis, MilesCriticism and interpretation.

2. Jazz19611970History and criticism.

3. Miles Davis QuintetDiscography. I. Title.

ML419.D39W38 2011

785.35195165dc22 2010020252

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS, ROBERT

AND EVELYN WATERS, FOR THEIR LOVE OF MUSIC

AND THEIR SUPPORT IN MY PURSUIT OF IT

SERIES PREFACE

THE OXFORD STUDIES IN Recorded Jazz series offers detailed historical, cultural, and technical analysis of jazz recordings across a broad spectrum of styles, periods, performing media, and nationalities. Each volume, authored by a leading scholar in the field, addresses either a single jazz album or a set of related recordings by one artist/group, placing the recordings fully in their historical and musical context, and thereby enriching our understanding of their cultural and creative significance.

With access to the latest scholarship and with an innovative and balanced approach to its subject matter, the series offers fresh perspectives on both well-known and neglected jazz repertoire. It sets out to renew musical debate in jazz scholarship, and to develop the subtle critical languages and vocabularies necessary to do full justice to the complex expressive, structural, and cultural dimensions of recorded jazz performance.

JEREMY BARHAM

SERIES EDITOR

PREFACE

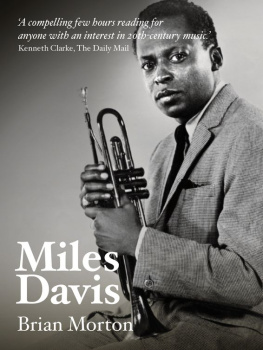

THERE ARE MANY VIEWS of Miles Davis. There is Davis the innovator, shaping the prominent jazz directions of postwar America, Davis the collaborator, relying on other musicians for creative tensions and foils, Davis the representative of a St. Louis trumpet tradition, Davis a constructor of racial identity and black masculinity in the 1950s, Davis the most brilliant sellout in the history of jazz, Davis the aloof and irascible, Davis the trumpeter engaged in signifyin, the propagandist for musical organization based on scales, the heroin addict, the champion over heroin addiction, the boxer, the searing melodist, the abstractionist, the owner of sports cars and expensive suits. And there are many others.

The inventory draws attention to a significant musician and complex cultural figure. It also highlights the plurality of views on Davis and his music. The intent for this book is not to examine all those facets, but to concentrate on those that relate to a specific set of studio recordings that Davis made with a specific group of musicians, his so-called second quintet, with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. The book uses transcriptions and description, calling attention to details of the music in order for them to be heard. It relies on a view of musical analysis that offers further ways to hear or think about those recordings.

Musical analysisand discourse on music more generallyis selective and provisional. It atomizes the music in particular ways, presenting some elements while ignoring others. The analyses presented here are no exception. They merely explore ideas that may be of particular interest to jazz musicians, listeners, writers, historians, and analysts, present features of the music that I think are audible but may not be immediately apparent, and consider ways in which these recordings broached or broke with jazz traditions.

Jazz studies has profited considerably by recent intersections with cultural studies. Such enterprises focus on jazz as a process that emerges from larger musical, social, and cultural relationships, and celebrates jazz as a collective endeavor. I am eager to acknowledge the influence of many recent writers in regard to collective processes, ensemble interaction, and the methods in which the players relied on one another in improvisational settings.

Yet occasionally such studies critique other approaches that allow more detailed views of musical organization, structure, and theorizing about them. The discomfort becomes especially acute when the focus remains on individual improvisations rather than on collective processes. The criticisms flow from several sources: that these analyses valorize the music by calling attention to features shared with Western classical music repertory (particularly features of coherence, continuity, or organicism), that they ignore larger collaborative processes and therefore favor product over process, or that they represent dominant academic institutional ideologies.

Yet jazz musicians as a general community are often keenly interested in and focused on details of musical organization and structure, are quick to theorize about these ideas, and frequently are savvy, passionate, and omnivorous in seeking out and using such details to facilitate musical development and growth. Further, published transcriptions related to individual improvisations by particular players, with or without commentary, have been an ancillary part of the jazz tradition at least since the 1927 publication of Louis Armstrongs 50 Hot Choruses for Cornet. It is not my intention to suggest that musical analysis arising from notated transcriptions plays a more fundamental role for musicians than other methods that they may cultivate. And it is certainly true that some analytical studies do privilege criteria such as organicism and coherence. (Andre Hodeir and Gunther Schuller are typically held as the culprits for unquestioningly establishing aesthetic values that mirror those of Western European music.) Yet jazz transcription and analysisboth of ensemble processes as well as individual improvisationsoften answer questions asked by communities of listeners, musicians, analysts, and writers, and form part of a long-standing tradition. It may be that those interested in jazz as seen through a cultural lens are interested in asking questions different from those with a more analytical focus. However, it seems that allowing for a plurality of views about music acknowledges more richly the breadth of its traditions.

Next page