Prelude: Paris 1919

The Council of Four is debating a complex issue concerning shipping in the Adriatic and Lloyd George is eloquently arguing the British case on which he has been briefed that morning by two of his officials, Dudley Ward and John Maynard Keynes. To their horror, over lunch, they agree that they have primed the Prime Minister to propose something contrary to British interests. They rush to the meeting too late, he is already speaking. As a forlorn hope Keynes passes him a note advising him to reverse the British demands and provides him with some points on which to base this new case. Even so, given the complexity of the problems, it must surely be beyond his capacity to do so. Spellbound they listen as gradually Lloyd George introduces a new line of argument, at first mere hints and indications, then a full flood of rhetoric which totally reverses his original position. He carries the day, persuading Clemenceau, Orlando and Wilson of the virtues of the British policy, using Keynes suggestions and adding a telling point of his own. The Welsh Wizard is at his brilliant best, the quickness of his wit and the magic of his silver tongue in the intimate setting of the Four has once more triumphed in the pursuit of British interests.

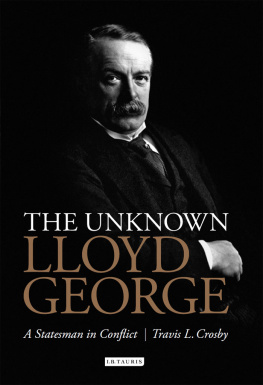

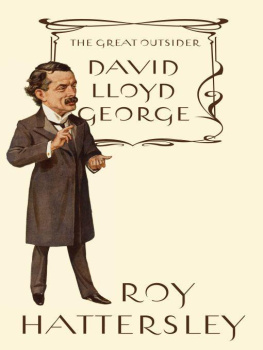

Paris marked the zenith of the extraordinary career of David Lloyd George, the Welsh Wizard. It provided him with a stage on which to exercise his considerable powers of persuasion, charm and deception, and an opportunity to shape a new world order. He was in his element, conjuring agreement from apparently impossibly opposed positions, reconciling the irreconcilable and smoothing the passage of the negotiations, always with an eye to British aims and ambitions as he interpreted them. He would remain Prime Minister for a further three years, years not without significant achievements though not on the grand scale of Paris. Then at the age of 59, relatively young for a politician, he left high office for ever, though he cast a long shadow over the domestic and international politics of the next two decades.

The Rising Star

William Orpens Peace Conference portrait of David Lloyd George shows a vibrant, genial, smiling figure, with a bristling moustache and a shock of white hair. It conveys much of the wit, energy, vitality and sheer exuberance of a man who was revelling in the excitement of the largest and most significant peace conference of the 20th century. The premiership of his country, a major perhaps the leading role in the Paris negotiations at the end of a war that he was credited with winning, were hardly predictable as the fate of someone born in relatively humble circumstances in Chorlton-on-Medlock near Manchester on 17 January 1863. His schoolmaster father, William George, died in 1864, leaving his mother, Elizabeth, pregnant with his brother William, his elder sister, Mary Ellen, and 18-month-old David. They moved to Llanystumdwy, near Caernarvon, North Wales, finding a home with Elizabeths brother, Richard Lloyd, a shoemaker and pastor in the nearby Baptist chapel in Criccieth.

Uncle Lloyd was a huge figure in Davids life even beyond his death in February 1917. All that is best in lifes struggle I owe to him first he told his wife, Maggie. He gave him his name and steeped him in Welsh identity and language, education, non-conformist religion, oratory, Liberalism and radical politics, and provided him with a moral compass. Yes how often have I kept straight from the very thought of the grief I might give him. Perhaps it would be unwise to overstate this aspect. Many of those who came into contact with him later might have found it ironic that Davy Lloyds first public appearance was singing Cofia, blentyn, ddwed y gwir (Remember, child, to speak the truth). David provided evidence of all these influences, organising, at 12, a strike of his schoolmates, who refused to recite the Anglican catechism for visiting local gentry. The strike lasted until brother William cracked. From that time onwards David had an enduring dislike of the predominantly English rural landowners in Wales and sympathy for their estate workers.

The 1880 Burials Act permitted Nonconformists to conduct burials in parish graveyards, using their own rites. The rector of Llanfrothen persuaded the donor of additional land for the graveyard to stipulate that only Anglican burials would be permitted. Robert Roberts wished to be buried beside his daughter, with a Methodist service. The rector refused permission. Lloyd George advised the family to break into the graveyard, conduct their service and bury Roberts. The rector sued them for trespass. Lloyd George persuaded the jury to find for his clients, but the judge, misinterpreting the verdict, found for the rector. The appeal to the High Court was successful, gaining the young lawyer much publicity.

Uncle Lloyd had belief in his nephews ability: It has often struck me how remarkable his confidence has been in my some time or other doing great things. He determined that David should follow the law.

He approached his goal in a systematic way, honing his oratorical skills, getting his name well-known in the local press both in terms of his legal practice, particularly in his defence of poachers, and his involvement in political controversies. Never one to avoid confrontations with the Establishment, whether the Anglican church or the local squires, his success in the Llanfrothen burial case in 1888 came at a particularly opportune time, helping him to be nominated as the Liberal candidate for the constituency of Caernarvon Boroughs.

In 1889 he was elected as an alderman on the new Caernarvon county council, but his major breakthrough came in April 1890, when, at the age of 27, following the death of the Conservative MP, he won the ensuing by-election by 18 votes. He would defend the seat 13 times, somewhat precariously in the early years, and remain continuously as the MP for Caernarvon Boroughs until, perhaps rather sadly, he took a peerage in January 1945. It had been offered kindly by the Prime Minister, his old friend Winston Churchill, to spare Lloyd George another electoral campaign, which was not guaranteed to be successful. He accepted, not from love of titles, which he despised and cheerfully bestowed or sold as Prime Minister, but because he hoped to influence the second Paris Peace Conference as a distinguished elder statesman. Churchill himself would not follow the same path, preferring to remain the great commoner and, in the event, Lloyd Georges death in March would have spared him a new election.