Authors note

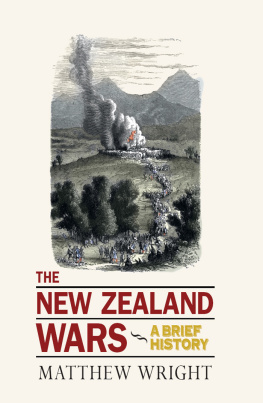

This brief history of the New Zealand Wars is a fully revised and updated edition of my book Fighting Past Each Other (Reed, 2006). For in-depth detail, full references and analysis, refer to the companion volume, Two Peoples, One Land (Reed, 2006).

Visit Matthew Wright online at:

http://www.matthewwright.net

www.mjwrightnz.wordpress.com

Published by Libro International, an imprint of Oratia Media Ltd, 783 West Coast Road, Oratia, Auckland 0604, New Zealand (www.librointernational.com).

Copyright 2006, 2014 Matthew Wright text

The copyright holder assert his moral rights in the work.

Copyright Matthew Wright photographs as indicated

Copyright 2006 Suzy Brown illustrations

Copyright all other illustrations as credited

This book is copyright. Except for the purposes of fair reviewing, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, any digital or computerised format, or any information storage and retrieval system, including by any means via the Internet, without permission in writing from the publisher. Infringers of copyright render themselves liable to prosecution.

ISBN 978-1-877514-68-5

eBook 978-1-877514-69-2

Cover design: Athena Sommerfeld

First published 2006 by Reed Publishing Ltd

This edition 2014 by Libro International

Printed in China by Nordica

Contents

The New Zealand Wars began in 1845 and lasted, broadly, for a generation.

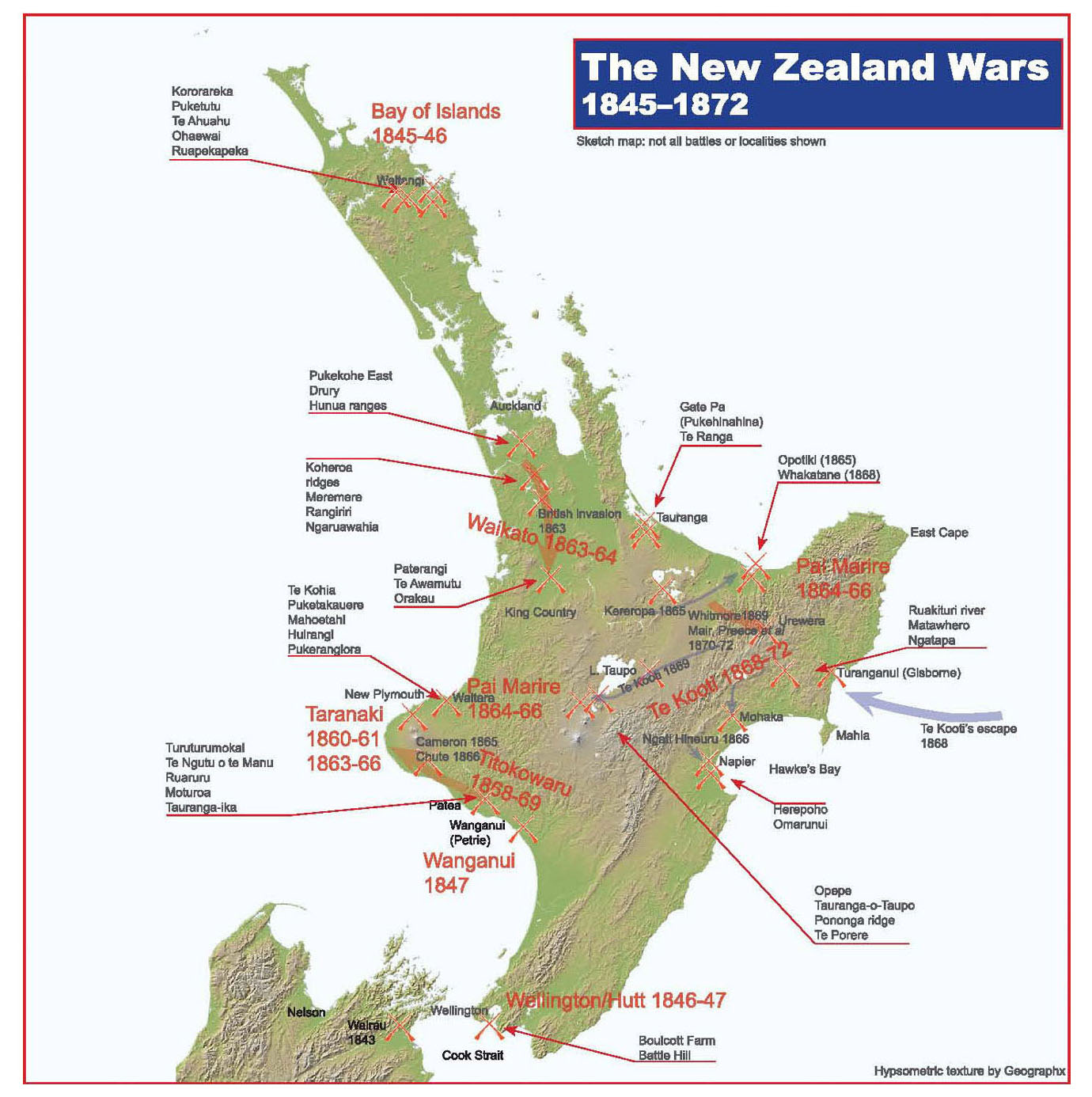

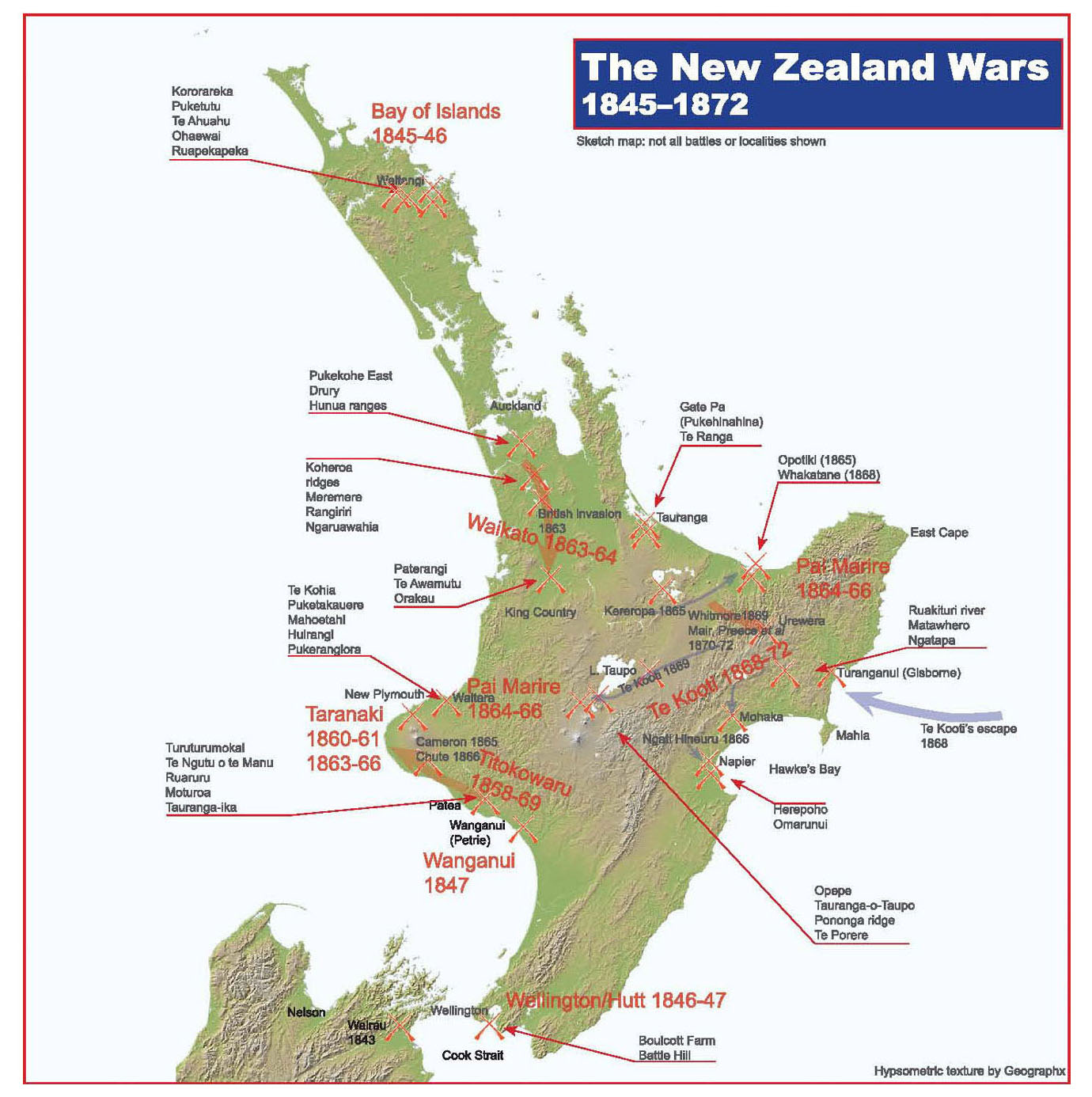

They were fought in succession across the North Island, from Northland to Wellington, from Taranaki to Hawkes Bay, and into the Waikato and Urewera. Popularly, they are held to have ended in 1872, when the last shots were fired. However, peace had not been made with the King Country and the New Zealand government continued military preparations well into the 1880s. Realistically, the wars never ended; as time went on the field of conflict simply shifted from the battlefield to Parliament and the courts.

These wars have been called by many names, including the Maori Wars, the Land Wars and the Colonial Wars. The names are unsatisfactory because each implies something only partly true about why the wars were fought, and what they represented. The term most often used today is the New Zealand Wars, which remains the simplest way to describe them.

Few people at the time and few historians since have agreed on what the wars meant. To settlers of the mid-nineteenth century, the wars supposedly ended with Maori making peace, becoming the best of friends, and giving New Zealand the best race relations in the world. Maori thought otherwise, for there were many injustices from the settler era that had not been resolved.

In the late twentieth century a new generation of historians re-examined the wars and demonstrated how the settlers had mythologised events. However, this re-writing As we shall see, this is nonsense.

Suzy Brown

The only real point of agreement is that, one way or another, the New Zealand Wars helped make New Zealand what it is today. They shaped the way race relations developed in the settler period and afterwards, although not quite in the way settlers thought they did.

The wars also shaped New Zealand in physical ways that we experience, use and even live in to this day. In the early 1860s, the Great South Road, south of Auckland, was built by the British Army. Cambridge was founded as a war town and Hamilton was named after John Fane Charles Hamilton (182064), the Royal Naval officer who fell at the battle of Gate Pa.

Today, many of the battle sites are half-forgotten, but we can still find them; they remind us that these are wars we can still touch. Many of the pictures in this book are of the battle sites today, selected to underscore the fact that the past is still all around us. We can stand where battles were fought in a few cases, even within some of our towns and cities and we can imagine what it might have been like to be there. We can understand from this that our history is not some dry, remote list of events. It is about the shapes and patterns of the past that make us what we are today underscoring the point that history is really a way of understanding the present.

What is clear is that the New Zealand Wars were fought at a difficult time in New Zealands history. This was the moment when Maori after half a millennium in isolation at the bottom of the South Pacific came into collision with the might of an industrialised economy. The wars were also a product of their time, an era when attitudes, ideas and thinking were very different from those of later decades. And they created injustices, some of which remain unresolved in the early twenty-first century.

Memorial to the Battle of Boulcotts Farm, central Lower Hutt.

Matthew Wright

Grave of casualties from HMS Hazard, Russell.

Matthew Wright

Remembering the wars

Many of the battle sites of the New Zealand Wars are marked. Some became churches. Others have memorials raised nearby. In other places, such as Christ Church in Russell, we can find the graves of those who died during the fighting. A few battle sites particularly Ruapekapeka, near Kawakawa in the Bay of Islands have become important historic sites and been restored with interpretation boards.

. Ross Calman, The New Zealand Wars, Reed, Auckland 2004, p. 29.

The New Zealand Wars were fought by a surprising range of people.

Professional British soldiers, occasionally joined by sailors and Royal Marines, were prominent until the mid-1860s. The colonists also provided settler soldiers drawn from the ordinary townsfolk of places such as Auckland, New Plymouth, Napier and Gisborne. Some of these were former regimental soldiers, often Irish, who had sought their discharge in New Zealand. But outside these one-time professionals, relatively few settlers were well trained in fighting. Many had been ordered to serve by law. Others offered to fight.

In the late 1860s, the New Zealand Government set up an Armed Constabulary, an army by another name, again with a fair number of former regimental soldiers among its ranks. The constabulary was joined by mercenaries, including the Austrian soldier Gustavus von Tempsky, who became one of the colonys popular heroes.

Maori fought on both sides, a consequence of the fact that there was no single Maori nation. Different hapu (groups of families) and iwi (groups of hapu) were related by family ties, but independent of each other until the British arrived. As settlers poured into New Zealand, many hapu and iwi drew together to form the Kingitanga, the Maori King Movement.

However, prior alliances and earlier disputes still shaped the way Maori responded to the conflict. Sometimes the precedents went back many generations; but in the mid-nineteenth century there was also a much more recent issue that shaped Maori response. New Zealand had been riven, for a generation prior, by the so-called Musket Wars. These wars had turned land rights upside down in some areas, just as the British arrived. That spurred disputes between Maori. Precedents from Musket Wars incidents unrelated to land purchase also provided reason, occasionally, for some rangatira (chiefs) to join the settlers in the conflict. Rapata Wahawaha, who had been enslaved by Rongowhakaata of the Turanganui (Gisborne) district in the 1820s, took the opportunity to avenge himself by joining the settlers.