THE NEW ZEALAND WARS

Many of us have been brought up on a kind of history which sees the human drama throughout the ages as a straight conflict between right and wrong. Sooner or later, however, we may find ourselves awakened to the fact that in a given war there have been virtuous and reasonable men earnestly fighting on both sides. Historians ultimately move to a higher altitude and produce a picture which has greater depth because it does justice to what was thought and felt by the better men on both sides.

Sir Herbert Butterfield

T HE N EW Z EALAND W ARS were a series of small campaigns fought between Britain, its colonists and the nascent government of New Zealand, and some of the Mori inhabitants. They spanned a period of nearly thirty years between 1845 and the early 1870s, although some historians consider that they continued through to Parihaka in 1881 and even to the arrest of Rua Knana at Maungaphatu in 1916. The wars have had a dramatic effect on the governance, land ownership and development of the nation through to the present day. They have cast an immense shadow across the nations history, they are the origin of many of the issues that have caused ongoing friction between Mori and the Crown, and they continue to fuel anger and disaffection among various interest groups today.

The first of the wars flared up a mere five years after the two races had appeared to have made an encouraging start towards building a nation together. In simplified terms, the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi), signed on 6 February 1840, promised a partnership between the two peoples, and as the various chiefs signed the document, Queen Victorias representative, Captain Hobson R.N., who was soon to become the first governor of New Zealand, is said to have uttered the words he had no doubt just learned: He iwi kotahi ttou; we are now (all) one people.

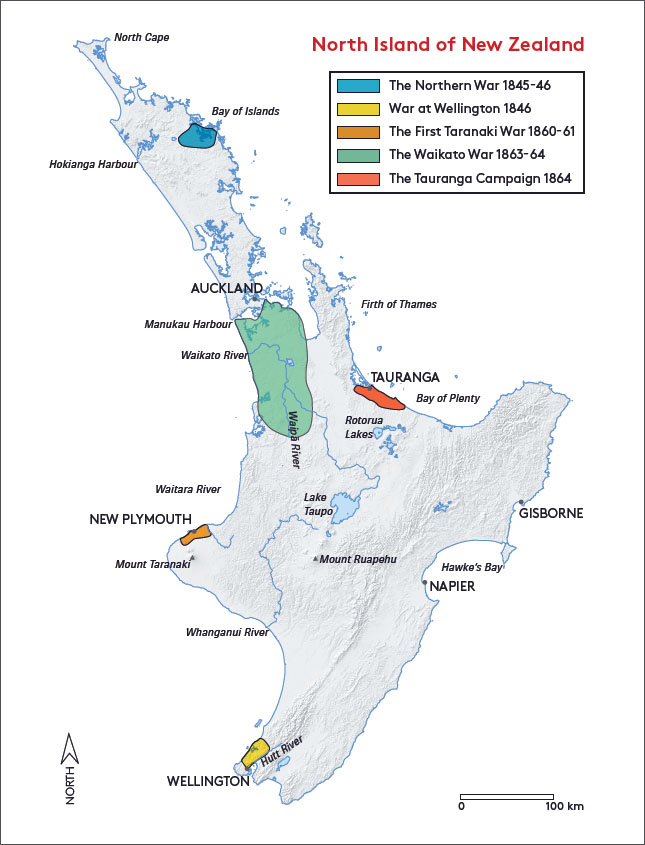

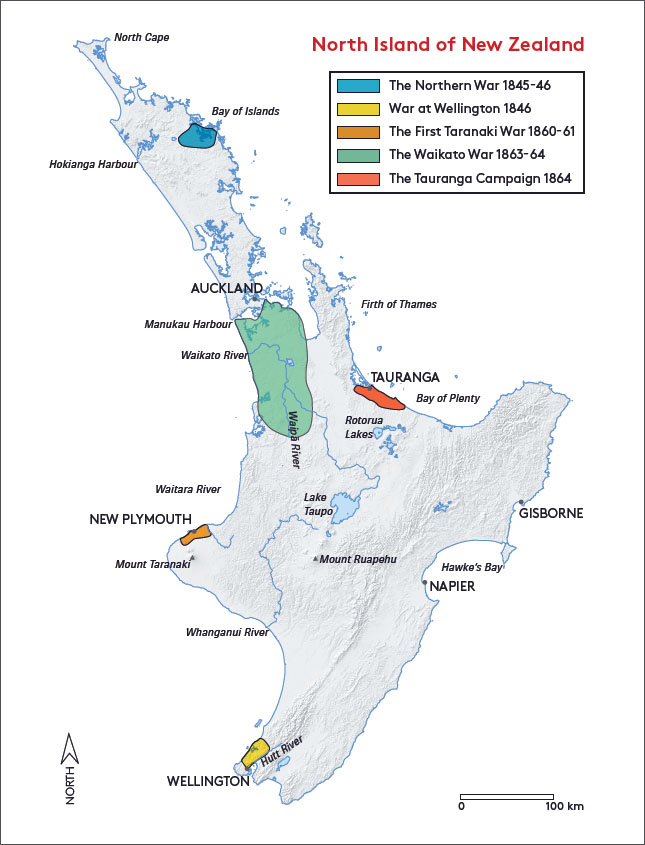

Map of the North Island showing the five major areas of conflict of the New Zealand Wars, 184564

(highest chieftainship), which were, and still are in some ways, irresolvable; the practical realities of how British law would be applied and how it would intersect with Mori custom and lore; and the ability of a new governor to rule fairly and justly and what the parameters and scope of that rule would be, were all tested in those early years.

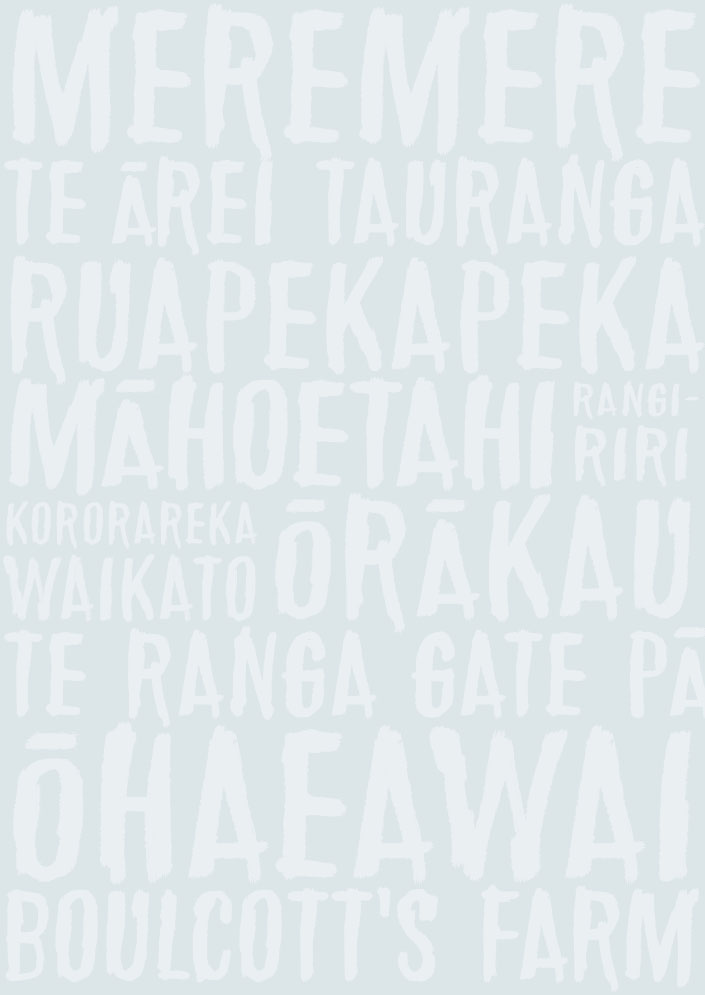

Armed conflict on a minor scale occurred in several places, and by 1845 any optimistic feelings were shattered as underlying concerns about chiefly authority and the loss of trade and income after the capital moved to Auckland provoked disillusioned factions of the Ngpuhi iwi into challenging the new British authority by force of arms. And so erupted the Northern War of 184546, which was fought in the Bay of Islands (Te Tai Tokerau). As soon as hostilities in the Bay of Islands ceased in early 1846 they ignited in the Wellington (Te Whanganui a Tara) region and then spread to Whanganui.

A decade and a half later, the wars of the 1860s began when the Mori and Pkeh populations were more or less equal in size. The rapid influx of mostly British settlers eager to begin new lives in this fledgling colony had created an insatiable demand for land, and the incompatible Pkeh and Mori attitudes to the ownership or rights to land again brought the two peoples into conflict. There was a growing realisation among Mori that the independent authority of their chiefs, and the economic and social survival of their people, lay in their ability to retain their land, and they developed pan-tribal methods to resist further losses of it. And so again wars were fought over the issues that have remained a constant in the relationship between Mori and the Crown: land and sovereignty.

Although New Zealand was a small colony at the extreme edge of the British Empire, as far away from the United Kingdom as it was possible to be, a significant British military force was assembled in each of the conflicts. The government used British imperial soldiers and sailors supported by local volunteers, militias and Mori allies in wars in the Bay of Islands (184546), Wellington (1846), Taranaki (186061), Waikato (186364) and Tauranga (1864). These are the conflicts examined in this book. The British imperial regiments and the Royal Navy continued to campaign but by the end of 1866 most had left. The last to depart New Zealand shores was the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot in 1870.

New Zealand embarked on a self-reliant defence policy in 1867 and it was the Armed Constabulary, the countrys first national army, that, along with Mori allies, fought guerrilla-style campaigns against the Hauhau (Pai Mrire) movement, a religion which sprang up in 1864 against the confiscation of Mori land, and the charismatic leaders Ttokowaru and Te Kooti between 1865 and 1872. Once the tribes had been defeated, or at least subdued, the government confiscated vast tracts of land and began the process of settling new immigrant farmers onto it. The New Zealand landscape still tells the story of these conflicts. Many of the sites have been ploughed and grazed into oblivion but there are remnants of p and redoubts, trenches and blockhouses, and graveyards and memorials that dot the countryside that speak of the nations painful past.

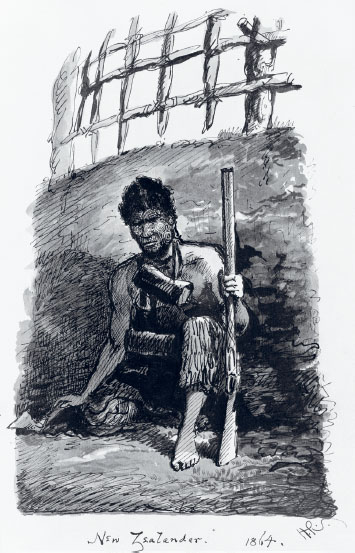

The British Army and Royal Navy were among the best in the world at the time and were large, modern, well-organised, professional forces of the European model. By contrast, the Mori warriors who opposed them were part-time fighters of a still largely subsistence society. The conflict between these two groups took on a range of guises, at times bloody and intense and at times interludes of armed vigilance. The battles ranged from set-piece assaults against well-constructed fortifications to insurgent campaigns in dense and trackless bush.