Britains Empires

Britains Empires

A History, 16002020

BY James Heartfield

Contents

Part one

The Old Colonial System, 16001760

Part Two

Empire of Free Trade, 17601870

Part Three

Modern Imperialism, 18701947

Part Four

Commonwealth, 194789

Part Five

Empire of Human Rights? 19902020

Britains Empires grew from the moment Norman England began to unite with or colonise its neighbours. Over the centuries, Britain came to dominate the Atlantic seaboard, the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, working inland to dominate Mughal and Maratha India, planting a new Anglosphere in Australasia and in the late nineteenth century vying with European rivals to carve up the African continent. While my grandparents lived in an empire that dominated a quarter of the globe, I grew up in the flickering embers of one, always just visible in the corner of your eye but still shaping much of British public life, as it impacted disproportionately and often destructively on the peoples of the rest of the world.

Looking at the question of Empire there are two different approaches. One looks at the longue dure the more than half a millennium of conquest (14922019) the other looks at imperialism as a specific epoch (18801914), and an era of transition.

Here, we are looking at the longer span but there is a problem with the longue dure. In the heyday of the Empire, it was common for patriotic Britons to laud its history from Francis Drake overcoming the Spanish Armada in 1588 right through to the wonders of the British Raj in 1938 as though it was one great cavalcade of glorious victories.

Today, with a different moral judgement, many critics of European empires see them as 500 years of unrelenting oppression. Those are both judgements that situate you morally in relation to the Empire, the first positive, the second negative. There is a point to both judgements. Institutionally speaking there is indeed a continuity to the British and other European states that made empires across the world. That is what the Royal Family represents, the single line of inherited order. More, the relationship between the mother country, England (later Britain) and its colonies has as a constant feature throughout all those years, an inequality of power, whereby it dominated those other peoples that it succeeded in colonising across the world.

By taking the whole five centuries as a single continuum you can lose sight of the very different forces and motivations at work at different moments in the history of European empires. In the longue dure it is easy to imagine that the end result was pre-ordained in the early beginnings. Broad sweep historians are often tempted to imagine a purpose or plan where there is none, or where the plans people make have little relation to the much later outcome. (The word for such thinking is teleological, meaning end-inspired, and it is generally thought to be a delusion.)

Something like the longue dure idea is at work when critics put the label forever wars on the succession of post-Cold War interventions that the United States and Britain have fought, from the 199091 Gulf War through to the air attacks on Syria in 2016. Forever wars works as a cynical shorthand that excuses critics from looking hard at the different cases made for intervention, implying that these are mostly post-hoc justifications, not sincere. No doubt there is some point to that. Still, it is better to try to examine each conflict in its own right in the first place before deciding there is an overall pattern.

The belief that the later stages are set by the earlier is a common one, better suited to drama than history. Along with the myth of continuity there is a myth of origins that to understand a thing you have to find its sources. History is not like biology. The later development is not coded in the original seed, like DNA. At most the earlier developments are the foundations on which the succeeding generation make their history. In the writing of history, it would be truer to say that the later development tends to shape our understanding of the earlier period than the other way around. The Empire that developed in the nineteenth century was not pre-determined by the colonial system of the sixteenth century. There is no transhistorical essence that explains the successive British Empires, whether you call that English genius or White Supremacy.

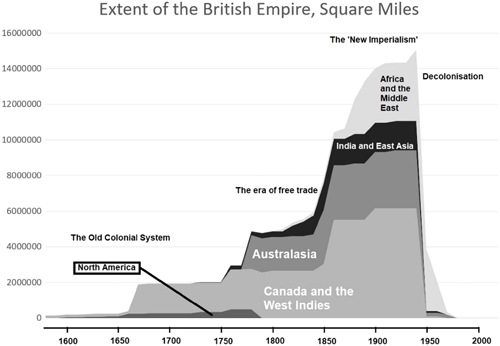

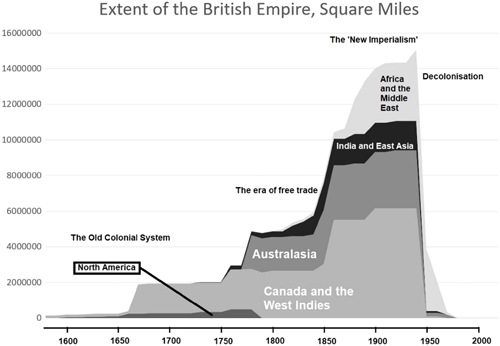

To make sense of the history of Britains successive Empires I have separated them into five successive eras, the Old Empire (16001776), the Empire of Free Trade (17761870), the New Imperialism (18701945), the Commonwealth (194689) and the New World Order (1989 to date)

The first is what, following Eric Williams and others, can be called the mercantile Empire. Royal monopolies like the East India Company, Hudsons Bay Company, the Merchant Adventurers and the Royal African Company dominated world trade mostly in luxury goods from 1600 to 1776. The importance of overseas trade was a marker of the underdevelopment of British commercial life. Dominated by customary relations, the countrys domestic realm did not readily yield to commercialisation. Instead, trade took off at the margins, in the port towns and with other countries. In time those monopoly companies began to be seen as a brake on further progress and were more openly criticised for their piratical excesses. In Part One we look at the role of the merchants and the monopoly companies, as well as the importance of the dynastic struggles and Renaissance characters in the transformation of British and European relations to the rest of the world. We look, too, at the importance of the early planters in the Caribbean and North America, and their spur to the slave trade.

Part Two looks at Britains reinvention as the workshop of the world as Disraeli called it following the repatriation of capital funds from overseas to make an industrial revolution at home. Britains early start in commercial society, its relative openness to scientific thinking and parliamentary democracy were admired across Europe. But when it was challenged by rival modernities in the revolutions in the United States and France, and also in Ireland and Haiti, Britains ruling class put the brakes on social change to impose a narrowly defined Empire of Free Trade. Commercial domination made the less developed world subordinate to British influence from the southern cotton fields of America to the cotton weavers of India. After the American revolution the British appetite for outright colonisation was abated. It would be wrong to say, though, that the era of free trade put an end to imperialism. That might seem a persuasive argument if you were to look at the Atlantic. In the Pacific Ocean, though, a new era of colonisation was underway, starting with the unlikely impetus of transportation, as English convicts, no longer expelled to the American colonies, were sent instead to Australia. Free settlement followed in Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and elsewhere in the Pacific, as it did in Canada and South Africa. The settlers were different from the planters and outpost traders. Many hoped to farm for themselves like English yeomen more than to lord it over grand plantations. Many left to escape Britain and they were in the first half of the nineteenth century, much disliked in the mother country.

Next page