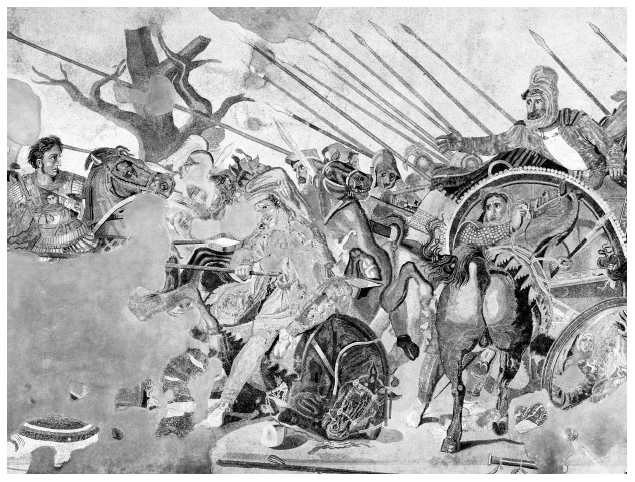

Facing title page: The Alexander Mosaic, House of Faun, Pompeii, c. 100 BCE (detail). (Berthold Werner)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

INTRODUCTION

The Lifespan of Empires

Empire is a dirty word in politics. Few today would call their nation an empire and mean it as a compliment or perhaps a bit of historic nostalgia. Also, in name at least, there are no empires left. There is still one remaining emperor in the world today, the emperor of Japan, and even that is based on a clumsy Western translation of the name for a uniquely Japanese position. True, part of the disappearance of de jure empires and emperors is the dramatic decline of monarchy as the preferred form of government on a global scale in favor of national republics, but it is also obvious that after the twentieth century, with its worldwide wave of decolonizing and liberation movements, the very word empire has come to conjure images of slavery, war, repression, and colonialism.

There are, of course, still dissenters. Popular British historian Niall Ferguson in particular has been an unashamed apologist of empire. Did Senegal ultimately benefit from French rule? Niall asks himself in an interview with The Guardian. His answer cuts clean. Yes, its clear.

Such defenses of empire, of course, alwaysand, to be blunt, have torefuse to even acknowledge the humanitarian ugliness. After all, empires are inevitably built through the hardship and displacement of entire peoples or at the very least economic exploitation of entire societies. Further, only the most callous would fail to be moved if they really meditated on how many lost cultures there are, absorbed and digested into nothing except a memory by expanding empires. Thanks to the Roman Empire, there is much that will never be known about the Etruscans, the Gauls, the Carthaginians, and the Dacians, while the wholesale destruction of Mayan codices and artifacts by seventeenth-century Spanish zealots erased a precious record of their religion, culture, history, and writing system.

Even the cool, rationalist praises of economic stability and growth under imperialism cannot be taken for granted. John A. Hobson, who lived at the time the British Empire was at its apex and still remains one of the great critics of empire, had a simple but devastating diagnosis for the seemingly prosperous British Empire of his day: Although the new Imperialism has been bad business for the nation, it has been good business for certain classes and certain trades within the nation. Whatever one gets out of this debatewhich no matter where one stands can only bring to mind the Jewish rebel leader in The Life of Brian who has to grudgingly admit that the Romans at least brought roads, aqueducts, sanitation, medicine, education, law and order, and wineit is hard to deny that the word empire, in our fiction as well as our politics, has become tainted. Even to some of those inclined to agree with him, Niall Fergusons rough claim that Africans were better off under European rule would strike many as obscenely heartless at worst or willfully contrarian at best, especially if thoughts of the atrocities committed in the Congo under Belgian rule come to mind.

None of this is to say that empires are confined to the past, and that entities that are empires by at least some reasonable definitions dont exist today. The countless articles and books speaking at least briefly of the decline of the American Empire, or comparing the United States history to that of Rome or the British Empire, say as much, as do the independence movements from Basque Country to Tibet that would without a doubt not hesitate to deploy the adjective imperial to help describe their plights. But it is hard to imagine even the most hawkish United States senator speaking candidly of Americasimperial interests in the Middle East or just using the word empire in open discussions of the nations future the same way British politicians did in the last century.

As with so many things, definitions are a conundrum. Most would agree, however, that empires dont have to fit the classical Roman mold, with thousands of soldiers marching in to occupy foreign climes. There are multiple species of empire and varieties of imperialism, such as cultural imperialism and economic imperialism. There are even empires that are paradoxically based on a promise of liberation, like the Enlightenment-spawned empire of Napoleon Bonaparte. Even in the face of so many variations, one may think, like Alexander J. Motyl, of empire as a system relying on separate parts working in balance, keeping one society in a dominant spot with two or more societies stranded in a subordinate position. What is important to wrestle out of the jumble of semantics is that empires can be subtle things, and that even countries that appear at a glance to be autonomous can be argued to be, at least in part, imperial subjects.

Whatever quibbles one might have in how to define empires, there are interesting consistencies across time and cultures. Empires are always almost organic things, born out of conflict, enjoying a healthy youth, navigating through times of crisis and recovery, enduring a debilitating old age, and finally facing a definite end. An army officer, Sir John Glubb, saw the British Empire at work firsthand in the Middle East and was inspired to write an essay titled The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival. Although admittedly only looking at empires from the history of Europe and the Middle East, Glubb theorized that empires usually have, at most, lifespans with an average of 250 years. However, Glubb at least concedes that the ways empires die vary, plagued by a plethora of outside pressures and internal illnesses.

Admittedly, as fascinating as the question of what causes empires to collapse and whether or not they have common factors that breach the barriers of time and geography, this book is no attempt to assess Sir John Glubbs hypothesis. Instead it is an exploration into the drama of imperial collapse through a series of vignettes. While I do not dare even try to fashion a universal theory of imperial decline, through this series of episodes of collapse I hope to at least delve into the many recurring ways an empire can falter: military hubris (Athens and Britain), destruction of a capital (Persia), alienating its subjects through oppression (Qin China and the Russian Empire), being dismantledby a rising power (Carthage), corruption in its heart (Han China), dynastic squabbles (the Carolingians), political disintegration followed by a sudden invasion (the Abbasid Caliphate), the marriage of sectarian conflict with cynical power politics (Byzantium), ecological catastrophe (Khmer), colonial exploitation (the Aztecs), the failure to achieve unity (Rome and the Mughals), and nationalist awakenings (the Ottomans and the Soviet Union).