Note on spellings and transliterations

There is no single agreed system for transliterating into the Western alphabet names, titles and terms from the different cultures and languages represented in this book. Each culture has separate traditions for the most correct way in which words should be transliterated from Arabic and other scripts. However, to avoid any potential confusion to the non-specialist reader, in this volume we have adopted a single system of spellings and have generally used the versions of names and titles that will be most familiar to Western readers.

About the Author

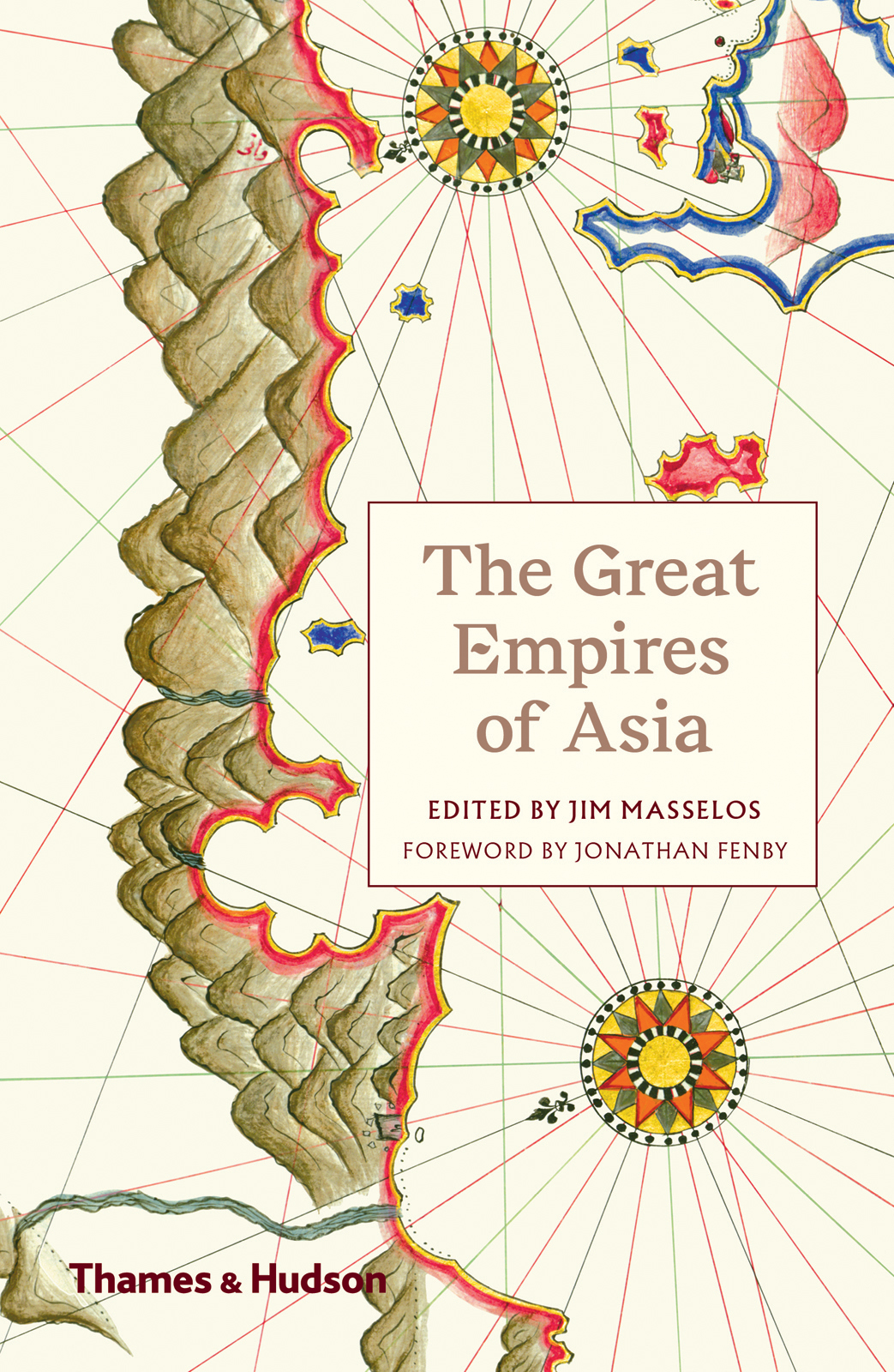

JIM MASSELOS is Honorary Reader in History at the University of Sydney, a fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, and author of several books on Indian history and culture.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Histories of Nations

The Great Cities in History

The Great Empires of the Ancient World

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

JONATHAN FENBY

JIM MASSELOS

TIMOTHY MAY

J. A. G. ROBERTS

HELEN IBBITSON JESSUP

GBOR GOSTON

SUSSAN BABAIE

CATHERINE ASHER

ELISE KURASHIGE TIPTON

JIM MASSELOS

JONATHAN FENBY

T he empires of Asia spanned 5,000 miles from the Pacific to the Balkans, marking the history of the planet for over a thousand years as they established realms that brought together a multiplicity of ethnic groups, cultures and religions. They were founded and led by some of the most extraordinary figures the world has seen: Chinggis Khan, the emperors of China claiming to hold the Mandate of Heaven, the Ottoman Sultans and the great Mughal emperor Akbar. They created capitals with architecture and cultural treasures to underline the awesome nature of their rule: the monuments of the Mughals, the Forbidden City of Beijing, the grandiose Suleimaniye mosque and Topkap Palace in Constantinople/Istanbul, the great edifices of Angkor and the mosques of Isfahan.

At the outset and often well beyond, military prowess was a constant theme as they fought to expand and then defend their vast territories. But rulers also had to develop systems of governance and bureaucracy to buttress their control while strengthening the economy of their domains and fostering trade that provided earnings for their subjects, tax revenue and links with other states. Their impact as they established themselves and then turned their conquered lands into imperial states is laid out in the seven chapters of this book, whose distinguished authors bring out the achievements and failings, similarities and differences, innovations and diversities that left an indelible print on history.

With the exception of Japans expansion after the Meiji Restoration, these empires were notable for their longevity. They lasted for several centuries or, in the case of China, for more than two millennia. The political, economic and cultural legacies they left have shaped lands from the Pacific to the Mediterranean to this day, providing a powerful backdrop to the evolution of the 21st-century world.

Unlike later European colonies separated from the seat of power by thousands of miles of sea, these Asian empires were primarily land-based so there was a direct geographical connection between the central capital and the further frontiers, with a melding of populations, customs and cultures along the route. That is not to say that maritime trade was irrelevant: with territories stretching round the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, the Ottomans had a formidable fleet, while Ming emperor Yongle sent admiral Zheng He on voyages through the seas of Asia and East Africa with a flotilla of huge ships to overawe local rulers and bring back treasure.

But the European model of using sea power for long-range conquest was not the way Asian empires operated. Rather, they followed a pattern in which the creators of empire established a base by defeating rival clans in local wars before expanding either to defend the homeland or in search of fresh territory. For the most far-flung empire of all, the Mongols, this process led from conflict on the steppes of north Asia to the throne of China, undertaking conquests as far west as the Black Sea and Ukraine, and reorganizing the nomad tribes into a nation that could field a million-strong army. At the end of this Asian saga, Japan played out in a relatively short time but on a huge scale the imperial syndrome by which the enlargement of territory or influence was required to confirm the new political order, which then needed to defend new, contested boundaries. This thirst for expansion and the strains it caused often came to spell the end of empires, even if the strength of the edifice constructed in the years of glory could stave off collapse for a long time.

While the empires and their rulers reigned supreme, with structures designed to buttress their authority, there was usually a degree of decentralization in such enormous territories. Conquered lands had to be made into entities that could contribute to the overall strength and prosperity of the empire. Far away in their capitals or out on military campaigns, sovereigns needed to ensure not only stability throughout their realms, but also supplies of food and goods for their troops and subjects. Smooth transport was essential to foster trade within and across imperial frontiers, and to guarantee the flow of tax revenue which commerce yielded. The construction of palaces and religious edifices required the mobilization of large labour forces from conquered lands even more so the Great Wall of China under the Ming or the canals and reservoirs of the Khmer.

So, once they had brought new regions under control, the rulers had every interest in melding coercive rule with a degree of conciliation. Governance systems needed to draw on the best and brightest of their subjects. Commanding territory that stretched from Afghanistan to South India, the Mughal emperor Akbar pursued a policy of incorporating defeated princes into the administrative system while allowing them to remain as active heads of their ancestral lands; he proclaimed peace to all and allowed freedom of worship. His overarching vision led the official historian to depict him as a semi-divine, enlightened father to his subjects.

The Ottoman empire, pre-dating the Mughals but outlasting them, can be seen as a set of concentric circles with core zones close to the centre, more remote frontier provinces and, even further away, loosely attached vassal or client states. The longevity of the emperors in Constantinople/Istanbul from 1281 to 1922 can be attributed, writes Gbor goston, to their flexibility, pragmatism and relative tolerance for centuries over peoples who followed multiple religions and spoke languages as diverse as Turkic, Greek, Kurdish, Slavic, Hungarian, Albanian and Arabic.

Once they had imposed themselves, empires generally offered a system of law and order and a bureaucracy that connected with the subjects, even if corruption and incompetence took hold when central control began to dissolve. It also offered tempting career prospects for ambitious young men if they joined the imperial service either as civil servants or as elite bodyguards and shock troops. For artists, architects and city planners, imperial capitals and courts provided a rich seedbed for achievement and innovation as the different chapters of this book make strikingly evident from the grandeur of the Taj Mahal and the monuments of Angkor to the finesse of Ottoman miniatures, the silk paintings of the Ming and the lines of Japanese prints. Safavid rulers of the sixteenth century presided over an extraordinary fusion of artistic achievement in painting, carpets, manuscripts, textiles, metalwork, book-binding and poetry, using resources from conquered lands to celebrate the greater glory of Persia.

Next page