First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 selection and editorial matter, Rhoads Murphey; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of Rhoads Murphey to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-4094-6678-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-58796-7 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

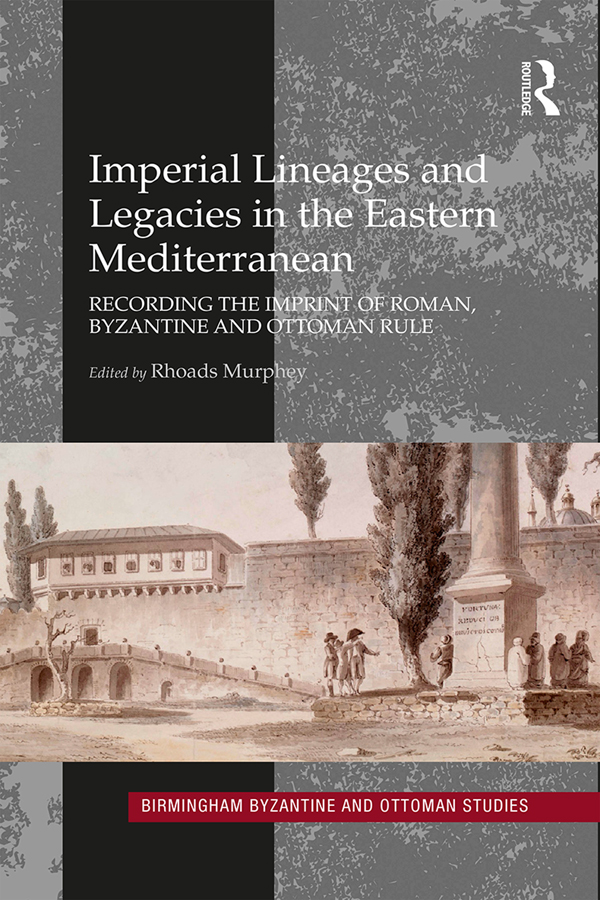

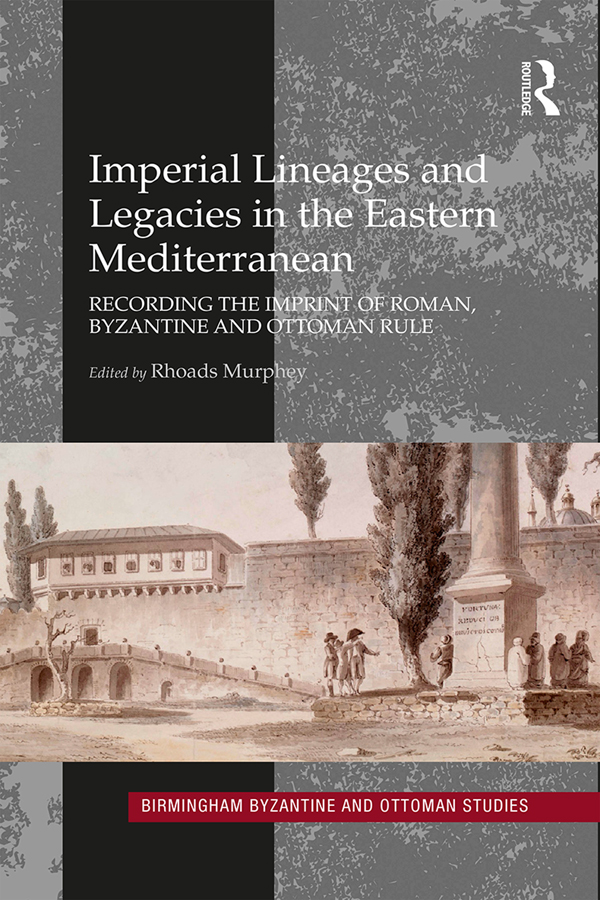

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies Volume 18

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies

General Editors

Leslie Brubaker

A.A.M. Bryer

Rhoads Murphey

John Haldon

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies is devoted to the history, culture and archaeology of the Byzantine and Ottoman worlds of the East Mediterranean region from the fifth to the twentieth century. It provides a forum for the publication of research completed by scholars from the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies at the University of Birmingham, and those with similar research interests.

For a full list of titles in this series, please visit https://www.routledge.com/series/BBOS

Sylvester Syropoulos on Politics and Culture in the Fifteenth-Century Mediterranean

Themes and problems in the memoirs, section IV

Vera Andriopoulou, Mary B. Cunningham Edited by Fotini Kondyli

The Emperor Theophilos and the East, 829842

Court and frontier in Byzantium during the last phase of iconoclasm

Juan Signes Codoer

Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest

Islamic architecture in the lands of rum, 12401330

Patricia Blessing

Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean

Recording the imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman rule

Edited by Rhoads Murphey

Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies University of Birmingham

Contents

JOHN HALDON AND RHOADS MURPHEY

ROSEMARY MORRIS

RHOADS MURPHEY

AGLAIA KASDAGLI

BEAT BRENK

LESLIE BRUBAKER

NATHALIE CLAYER

JOHANN STRAUSS

FREDERICK ANSCOMBE

JOHN BINTLIFF

ATHANASIOS K. VIONIS

11 Legacies in the landscape: the Vostizza district,

c. 14601715

MALCOLM WAGSTAFF

The unifying concept that links the eleven chapters presented in this volume has its origins in a conference convened under the joint auspices of the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies (University of Birmingham, UK) and the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (Ko University, Turkey). Thanks are due first and foremost to the Philip D. Whitting fund administered by the University of Birmingham, whose generous support covered the travel and accommodation costs of the twenty scholars who were brought together to take part in the International Conference on Imperial Legacies in a Cross-Cultural Context held in Istanbul in September 2011. Special thanks are due to Scott Redford, then director of the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations for securing financial support from his universitys rectorate and for arranging meals and hospitality, not to mention the free use of his institutes handsome and well-appointed premises, during the full extent of our tightly scheduled two-day meeting. As convenor of the conference as well as a participant in its proceedings, speaking both for myself and on behalf of the nineteen other participants, we would like to express our heartfelt thanks for his collegiality and support. I would also like to acknowledge the offer of financial support from the College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham, whose support from the Research and Knowledge Transfer Fund made possible a more generous quota for illustrations than was originally envisaged.

Although the papers presented at the conference were of a uniformly high calibre, during the process of revision and finalisation for inclusion in the present volume, the authors, myself included, benefitted from suggestions on the final chapter drafts that were made by a group of volunteers from among the doctoral students in Byzantine and Ottoman studies working under the supervision of John Haldon, a former colleague at the University of Birmingham and currently Shelby Cullom Davis 30 Professor of History at Princeton University. Professor Haldon also kindly agreed to offer some incisive remarks on the state of the field in the comparative study of empires for the introduction to the volume. As for his postgraduate students, with their agreement I am pleased to acknowledge their contributions individually and by name in alphabetical order: Merle Eisenberg, Vicky Hioureas, Rebecca Johnson, Sarah Matherly, Arianna Myers, Robyn Radway, Emily Riley, Morgan Robinson, David Walsh and Genie Yoo.

Finally, and certainly not least, I would like to express my personal thanks to John Smedley of Ashgate (now Routledge) publishing house for his unstinting help and support during the process of preparing the book for the press.

Rhoads Murphey

University of Birmingham,

Birmingham, UK, 19922014

Ipek University, Ankara, Turkey, 2014

Part I

Law and empire

Part III

Individual, group and corporate identity in an imperial context

7

Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire

Johann Strauss

Introduction: language and power in multi-ethnic empires

Language and power are closely connected, and there is a correlation between political and linguistic dominance. Whether classical nation states would impose one single language seems to have been a crucial, even vital question. France has been quite successful in this respect, as have modern Greece and Turkey. As far as empires are concerned, they used to meet with fierce resistance as soon as they attempted to apply the politics of the nation state and to impose a national language. There are the dominant languages: in such cases the need to become bilingual is only felt by the dominated language groups, who have to learn the dominant language, whereas the dominant speakers can use their language in all domains. However, a dominant language may lose this status. In that case, the decline of a language may also reflect a decline of political power.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the number of linguistic communities increased steadily in these empires, mainly due to conquests and annexations of new territories: in the Habsburg Empire after the annexation of parts of Poland, the Bukovina, Dalmatia and Northern Italy, which were added to already incorporated groups like Czechs or Hungarians. Equally conspicuous was the expansion of the Russian state: the Crimea, territories of Poland, Finland, the Caucasus and Central Asia all added new linguistic communities to the already existing Ukrainians, Germans, Tatars and others. In the Ottoman Empire an increase of languages appeared due to the mass immigration of Caucasian peoples (Circassians, Ubykhs, Chechens etc.), especially after 1864. We do not have censuses indicating the mother tongues of that period, but it can be safely assumed that the Turkish-speaking population of the Ottoman Empire did not form the majority. There were, the same as in the other empires, large territories (e.g., the Arab provinces) where the language of the ruling element was not spoken at all.