Dr Stienie Dikderm was born in Bethlehem, in a manger, because there was no room at the Holiday Inn in Welkom. Educated at Dominee Sweepklap se Skool vir Gereformeerde Meisiekinders, she completed her PhD in Historical History, with a thesis entitled Barefoot over the Drakensberg: Toe Jam and Bunions as Cultural Artefacts. She currently teaches Media-Relevant Historical Factoids in the Department of Media and Stuff and Whatever at the Technical University of the South-East, Umhlanga Rocks campus.

Professor Herodotus Hlope is a veteran of the Struggle To Get Published, having first stormed the barricades of publishing in the 1980s with a short novel about being young and misunderstood, entitled Being Young and Misunderstood. However, Academia beckoned (she was the manicurist who lived next door) and he married her in 1988. They have two children, Number One and Number Two (Prof. Hlope admits he is not good with names). Professor Hlope currently lectures in the Department of Relevance and Vibrancy at the University College of Technical Excellence, Boksburg Campus.

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.zebrapress.co.za

First published 2013

Publication Zebra Press 2013

Text Dr Stienie Dikderm and Prof. Herodotus Hlope 2013

Illustrations: Gretchen van der Byl

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: Marlene Fryer

MANGING EDITOR: Robert Plummer

EDITOR: Louis Greenberg

PROOFREADER: Bronwen Leak

COVER DESIGNER: Gretchen van der Byl

ISBN 978 1 77022 5947 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 5954 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77022 5961 (PDF)

We Fall Out of the Tree

I T WAS A WARM SUMMER night about three million years ago in southern Africa when our earliest human ancestor first came down out of the trees, by accident. He had been dreaming that he had to write a maths exam and was running out of time, and he lost his perch on his familys branch and fell out of the tree. What he saw was endless grassland, promising abundant life. What he did not see was the leopard behind him, promising instant death. He was bitten in half like a cocktail sausage and both bits of him were dragged into a neighbouring tree to be eaten later. It would be another 500 000 years until the next apeman came out of the trees, when Og the Flatulent was pushed off his branch by his family.

What did these early pre-humans look like? Fossil evidence reveals that they were muscular, hairy, covered in ticks and filth, and dragged their knuckles on the ground. In other words, they looked almost exactly like teenage boys. Like teenagers, they also spoke in short, aggressive grunts, and when confronted by older and wiser apemen, would storm back to their caves while screaming, That is so unfair! You are such a fascist! I wish Id never been born!

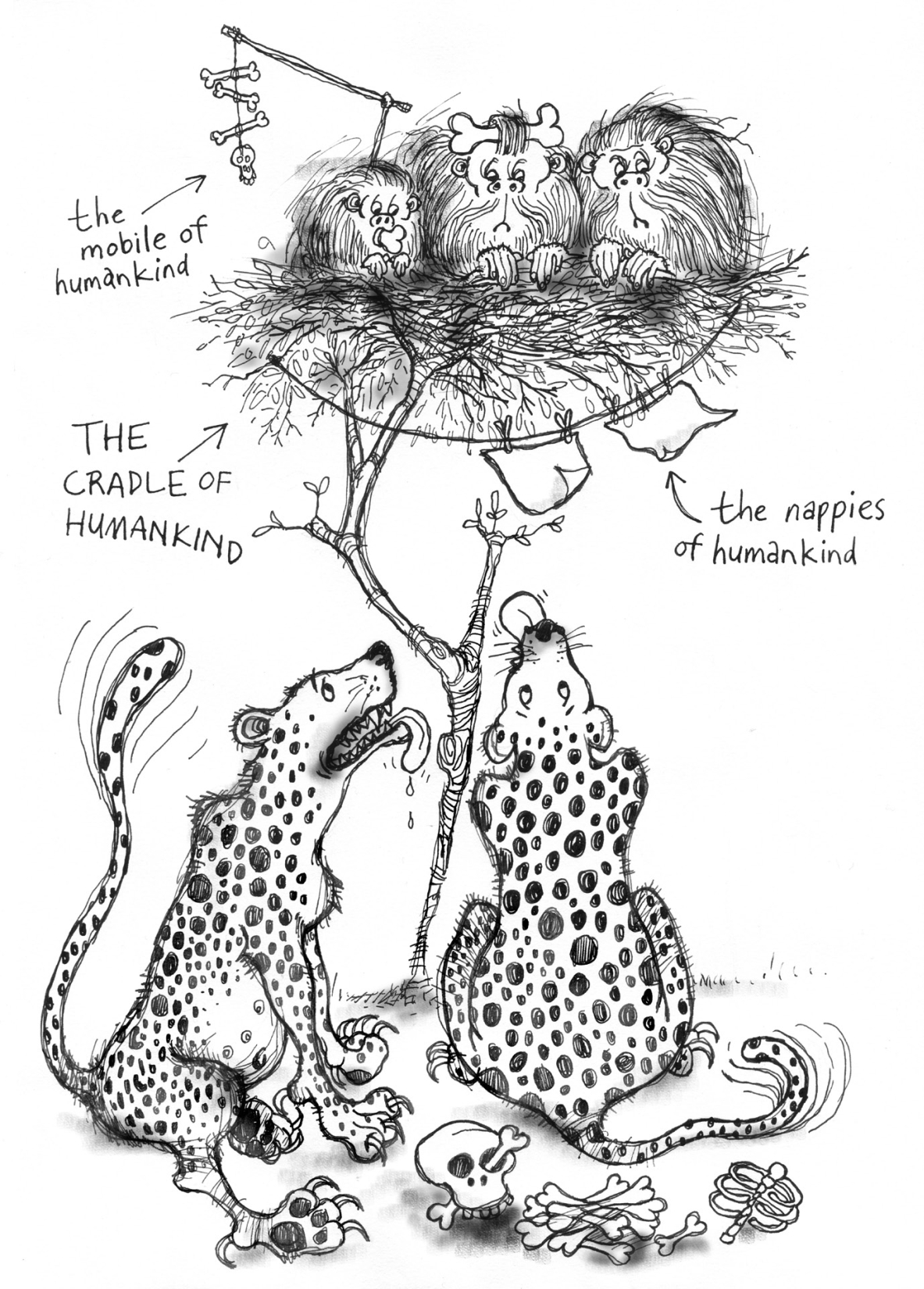

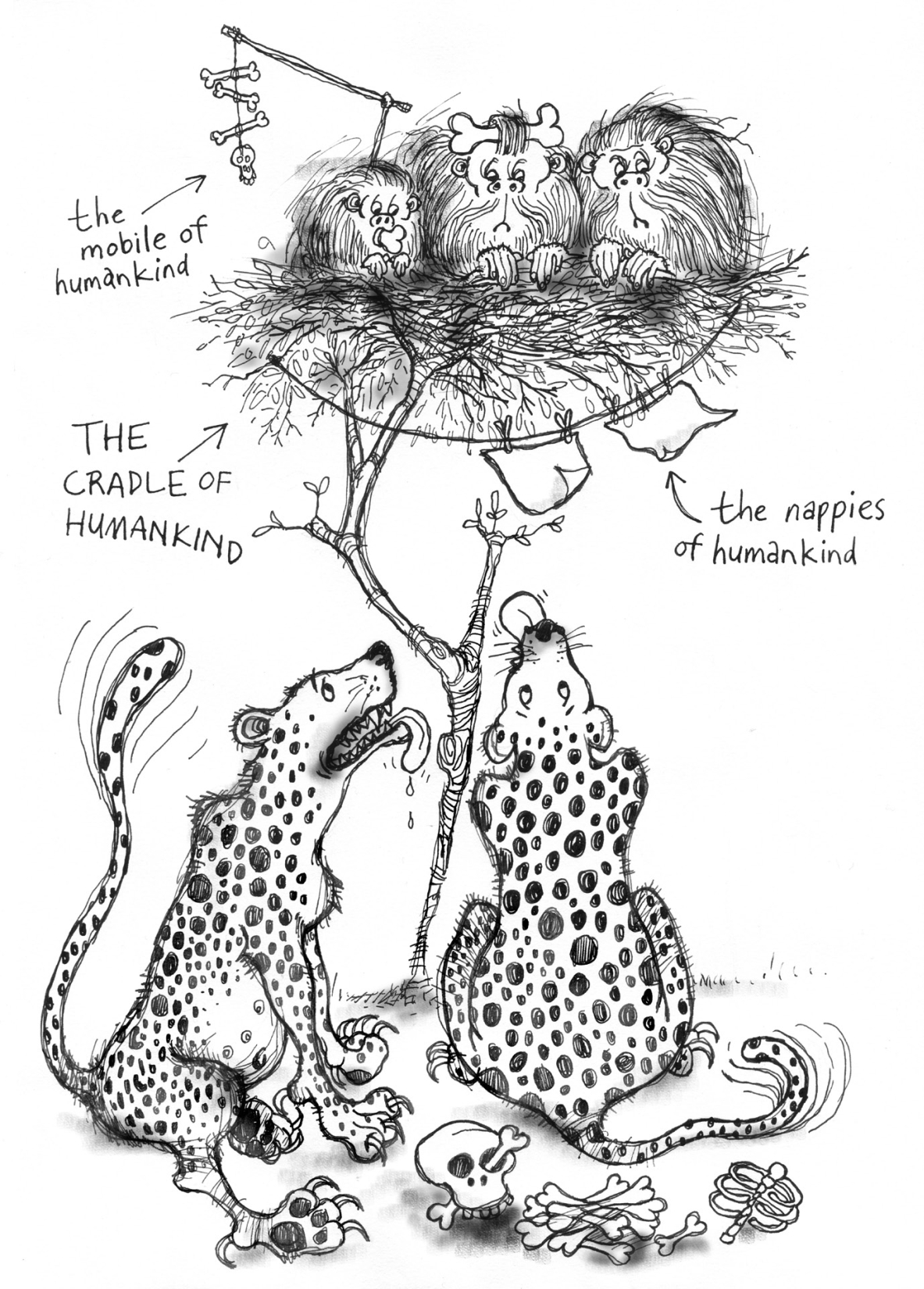

Life was indeed hard for our ancestors. The new world beyond the trees was full of problems, and solving these problems was very difficult with a brain roughly the size of a peanut. The Cradle of Humankind in Gauteng is one of the most famous sites of early human life, but it took millions of years before any ancient human even knew what a cradle was. The first attempt, the Flat Rock of Humankind, was simply a slab of granite and offered almost no lumbar support. Ten centuries later, they had managed to make the Shallow Dent in the Log of Humankind, but the log became infested with termites and was washed away in a flash flood. The next attempt was the Nest of Humankind, a rough collection of twigs and dust bunnies, but it failed to keep the draft out and was prone to catching fire during thunderstorms. A million years after starting work on somewhere to store their babies, ancient pre-humans finally figured out how to make the Cradle of Humankind. Having made this massive technological breakthrough, they could now settle down to more complex intellectual activities, like working out that fire was hot and water was wet.

But bigger brains brought their own problems. As their brains grew, achieving the size and mental capacity of a gemsquash, our ancestors realised that they had spent the last two million years building a Cradle of Humankind, but had entirely forgotten to build a Bedroom of Humankind to put the Cradle in. This also explained why they were still being decimated by leopards: without a Front Door of Humankind, they were sitting ducks.

A mood of pessimism settled over southern Africa, as worried hominids agreed that leopard crime was spiralling out of control. Many tried to boost the security around their caves, using porcupine spikes or carefully hidden snakes, but their gemsquash brains made this highly risky: hundreds perished while testing their home security systems by poking their boomslangs with quills.

For others, emigration was the only option. And so the first great migration out of Africa began, as gatvol apemen walked, swam, walked some more, and finally crawled to London and Perth. Those who ended in Europe evolved into Neanderthals. Those who ended in Australia evolved into Shane Warne.

Those who remained behind in Africa evolved quickly, splitting into subspecies like Drivus insanus taxidermens (literally, Drive in this taxi and you will end up stuffed), a people with brains incapable of telling right from wrong or left from right. In certain parts of the interior, around the Cradle of Humankind, a small and rare community of Platoformus takkies sokkiensis evolved with its own unique behaviours, such as migrating to the Hartebeespoort Dam every December to listen to very primitive techno-sokkie played on tortoise shells and reed flutes.

About 200 000 years ago, those living in the Cradle of Humankind had stopped evolving, mainly because they had been overwhelmed by the Nappies of Humankind, two million years worth of soiled diapers that had accumulated in the Cradle and made it almost impossible for them to live normally. Instead, it was in the southern Cape, near Port Elizabeth, where modern humans first fully emerged. (Since then, Port Elizabeth has failed to evolve any further.)

These first modern humans looked exactly like us, except with slightly more leopard-tooth punctures. Academics agree that if a child born eighty thousand years ago was raised by modern parents, we would not be able to see any difference between it and modern children. However, this is debatable: a child born eighty thousand years ago would be hideously wrinkly today. This might alert keen-eyed babysitters, especially if the eighty-thousand-year-old infant tried to stab the babysitter with a mammoth-tusk dagger.