FELIPE FERNANDEZ-ARMESTO

THE

AMERICAS

A Hemispheric History

A MODERN LIBRARY CHRONICLES BOOK

THE MODERN LIBRARY

NEW YORK

CONTENTS

LIST OF MAPS

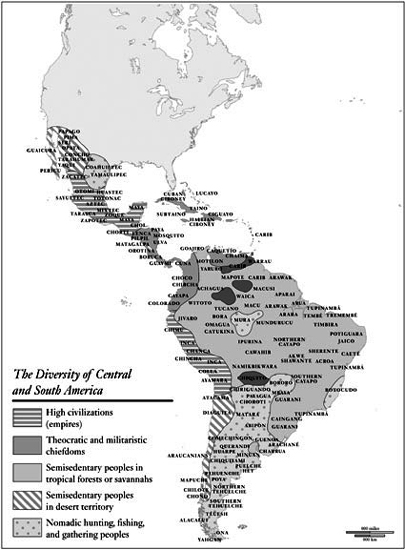

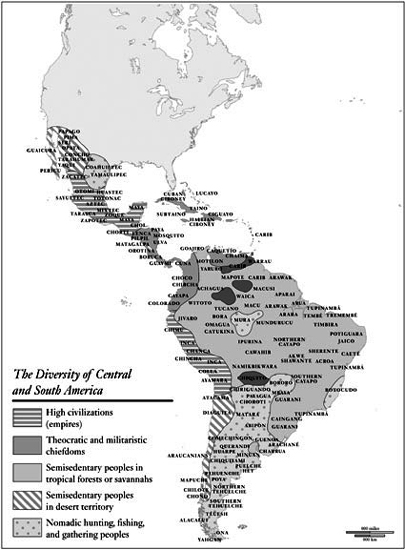

THE DIVERSITY OF CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA

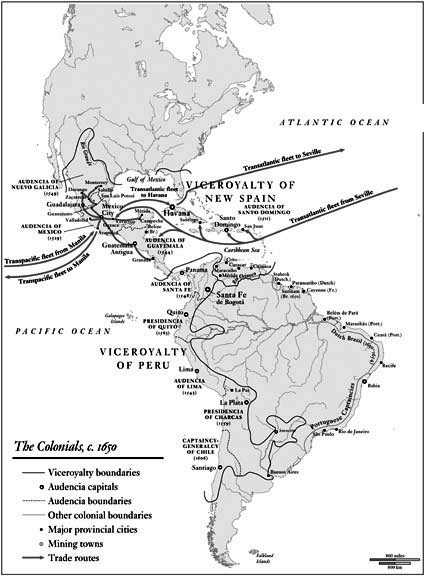

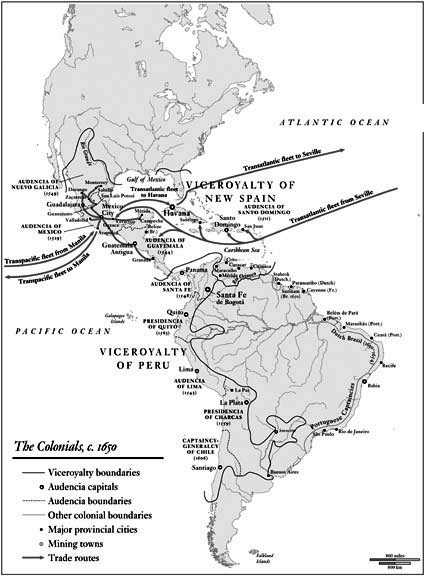

THE COLONIALS, C. 1650

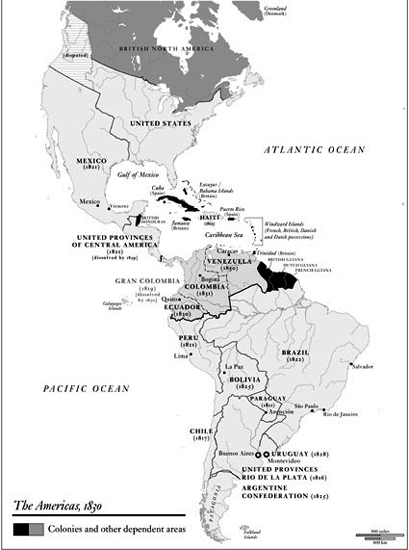

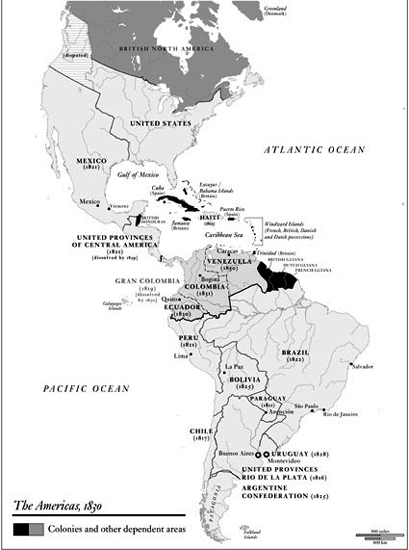

THE AMERICAS, 1830

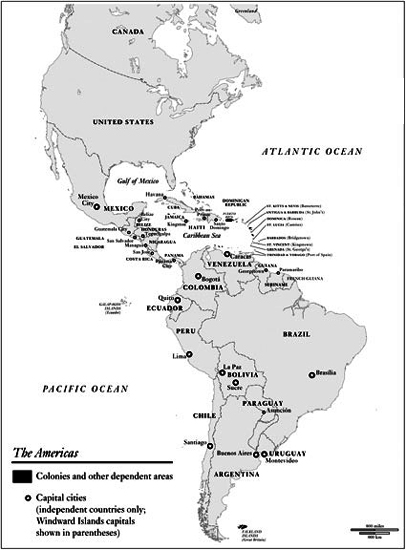

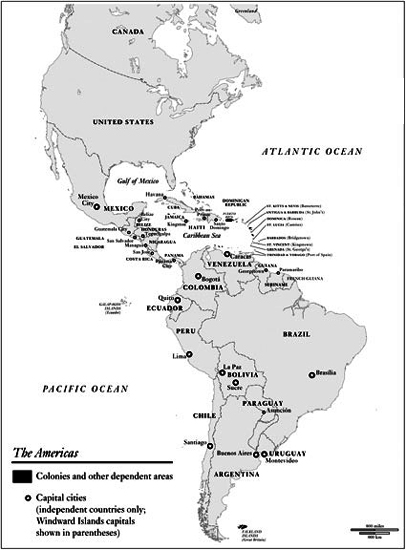

THE AMERICAS

AMERICAS? AMERICA?

Americans bicker over the name of Americans. To the chorus in West Side Story, America is a foreign land, where some of them like to be, a sentiment apparently inaccessible to them in Puerto Rico. Canadians write to newspapers in the United States complaining that the citizens of one country have usurped the appellation of Americans. The Spanish intellectual Amrico Castro was so called because he was born on a boat on the way to Argentina. In much of South America the people of the United States are called norteamericanos, whereas the northernmost Americans are actually Inuit and the United States reaches only the forty-eighth parallel. A character in Barcelona, Whit Stillmans film about U.S. expatriates trying to cope with anti-Americanism, resents the Spanish term estadounidense because it makes him feel despised as dense. Many of the names by which Americans call one anotherAnglos, Afros, indios, Latinos, Caucasianstug at other continents. The privileged names now enjoyed by some minoritiesNative Americans, indgenas, First Nationsimply an imperfect sense of belonging in everyone else. No usage suits everybody.

Yet America was once the New Worldpure and simple. It was possible to imagine it as a single category, a single polity, the home of a huge, embracing identity. Pan-Americanism no longer exists, except as piety or rhetoric. Like Europe, America is a Humpty-Dumpty continent. It has to be painfully reconstructed after the ravages of nationalism, across the fissures and fractures between which rival identities have formed. This book is an attempt at mental reconstruction of the hemisphere; an effort to see it whole and to trace a common history that embraces all the Americas.

AMERICAN SINGULARITY

How many Americas are there? Once, at least in the eyes of beholders who looked at the hemisphere from outside, there was only one. America possessed unity and integrity of a sort, long before it was well delineated. The term entered our languages in the singular. Amerigo Vespucci (or, at least, a writer using his byline) reported the first lands known as America from the coasts of what are now Venezuela, Guiana, and Brazil. Martin Waldseemller, the cosmographer who coined the name in Amerigos honor on a map and an accompanying treatise in 1507, rapidly regretted it; he realized that the honor of the discoveries he had attributed to Vespucci really belonged to Columbus. In his next map he suppressed the name, but it was too late. America extended, in contemporary imaginations, over the whole of an ill-defined hemisphere, which seemed to grow as successive expeditions explored further, unsuspected parts of it. The unity of the New World was apparent to most early explorers who reconnoitered it and early European cartographers who drew it. Some of them, at first, split it into two with a very narrow strait; others showed the New World as what we think of today as South America, while representing North America as a promontory of Asia. But the convention of showing the whole hemisphere as a single large landmass was well established in the second decade of the sixteenth century.

This is an odder, more intriguing fact than it may at first seem, since it was easier, in the years when the idea of America was first introduced to European minds, to deny the hemisphere altogetherdismissing the claim that it existed as fraud or delusionor to classify it as part of Asia. European geographers in antiquity and the Middle Ages speculated about the existence of an unexplored landmass in the unfrequented recesses of the western ocean. But belief in it was a minority indulgence, derided by skeptics. The idea that something as big and discrete as a new world lurked unseen, waiting to be discovered, seemed implausible to the Old World. Even writers of the medieval equivalent of science fictionromances of seaborne chivalrygenerally preferred to speckle the Atlantic with islands as settings for their heroes adventures. So did the makers of speculative sea charts (though a series survives of fifteenth-century maps that also depict a western continent, named after the daughters of Hesperus from the legend of Hercules, who raided their garden for golden apples).

Most cosmographers reviewing projects for ocean crossings in the fifteenth century dismissed the possibility that exploration would uncover a new continent. They thought they knew all the world there was. Even Columbus, who found a route to America, was disinclined to believe that such a place existed. Though his geographical notions were mercurial, and he was inclined to change his mind according to the fancies and prejudices of his audience, he generally favored the view that the world was too small to accommodate an unknown hemisphere; the new world he claimed to have discovered was, in his own estimation, really just a new part of the old onethe easternmost extremities of Eurasia, the Indies that the ancients had labored to reach.

Nevertheless, in the century or so preceding Columbuss voyages, the idea that something like America might really exist did gain some ground. Partly this was because of the movement we loosely call the Renaissancethe progressive rediscovery in western Europe of texts from classical antiquity. Mainstream geographical tradition in antiquity knew roughly how big the world was. In the third century B.C. the librarian Eratosthenes had measured it with tolerable accuracy. He proposed a value of about twenty-five thousand miles at the equator, in modern terms, using a mixture of trigonometry, which was infallible, and measurement, which was open to quibble. But there was clearly room for another worldthe Antipodes, as it was called by geographers who believed in it.

A number of fifteenth-century humanistspursuers, that is, of the anthropocentric curriculum recommended by classical scholarshipdrew attention to ancient speculations about the Antipodes. In 1423 one of the most suggestive ancient geographical texts arrived in Latin Christendom: Strabos defense, written in Greek in the first century B.C. of a picture of the world traditional since the time of Homer. Strabo placed the supposed unknown continent roughly where Columbus or one of the other Atlantic navigators of the time might have hoped to find it. It may be, he wrote, that in this same temperate zone there are actually two inhabited worlds, or even more, and in particular in the proximity of the parallel through Athens that is drawn across the Atlantic. In the context of Strabos thought as a whole it seems that this observation was intended ironically; but irony is notoriously difficult to detect in texts from an unfamiliar time or culture, and some of Columbuss contemporaries took the passage literally. As soon as Columbus returned from his first Atlantic crossing, humanist geographers began to speculate that he had reached the Antipodes. The more people learned about it, the more the identification solidified. The parts of the American mainland and islandsdespite their vastness and their multitudinous diversityfused into one.

Next page