Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE DOMINION OF WAR

Fred Anderson, professor of history at the University of Colorado, Boulder, is the author of A Peoples Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years War and Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, which won the Francis Parkman and Mark Lynton History prizes in 2001.

Andrew Cayton, distinguished professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, has written or edited eight books, including Frontier Indiana, a Choice Outstanding Academic Book, and Ohio: The History of a People.

Praise for The Dominion of War

The very best histories not only elucidate the past but illuminate the present. Far and away the most important contribution to U.S. military history to appear since this nation emerged as the worlds sole superpower, The Dominion of War meets and easily surpasses that demanding standard.

The Washington Post Book World

Anderson and Cayton aim at nothing less than a new grand narrative of American history.... Clearly The Dominion of War is meant to provoke, and it does, along the way vividly retelling the neglected aspects of the American story.

The Wall Street Journal

An incisive, provocative account of the U.S. rise to global preeminence over five centuries.... Anderson and Cayton have provided a well-written and important reinterpretation of our past.

Booklist

History in an ironic key, timely and provocative.

Kirkus Reviews

This sweeping reinterpretation places war and empire where they should benot as exceptions to the American past, but as central to it, and therefore to the United States today.

Michael Sherry, author of In the Shadows of War: The United States Since the 1930s

Fred Anderson and Andrew Cayton have given us the most important book ever written on the connection between war and American expansion. The erroneous overemphasis on American exceptionalism receives, in The Dominion of War, another telling body blow. Their story of American imperialism shows how much we have been like other powerful nations in history. It should be required reading for our political leaders today as they grapple with the consequences of American overstretch.

Don Higginbotham, author of The War of American Independence

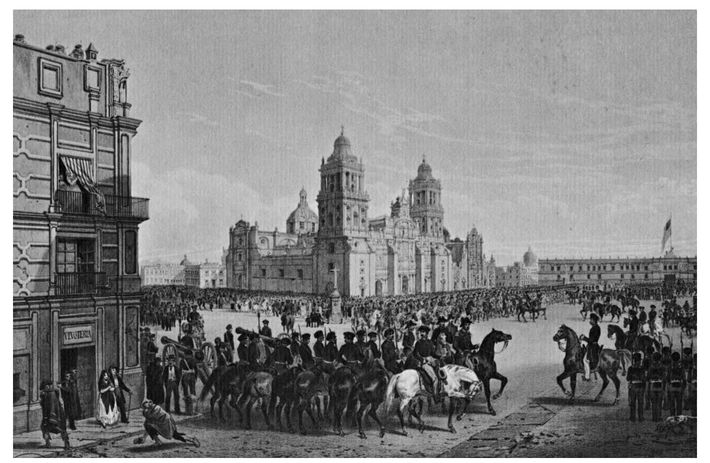

Mexico City, September 14, 1847. The entrance of the U.S. Army under Winfield Scott.

For Samuel DeJohn Anderson, And for Elizabeth Renanne Cayton and Hannah Kupiec Cayton, with love.

The Vietnam War Memorial at sunrise Brian G. Green/National Geographic, ngs0_7802/Getty Images

Introduction

A VIEW IN WINTER

The Mall in Washington, D.C., is a good deal less inviting in January than in April, when the cherry trees around the Tidal Basin burst into bloom and tourists loiter in the sun. But because the ways in which the Mall and its monuments give meaning to the events of American history are clearest in the winterand because the story we have to tell is in many ways a wintry taleit may not be amiss for us to begin on the Mall with the trees bare and the skies gray, walking down the path that leads from the Lincoln Memorial to the Vietnam War Memorial. In spring, the transition between the two would be muted by the trees and plantings of Constitution Gardens. In winter, the contrast is stark and unmistakable.

Behind us, the majesty of the Lincoln Memorial leaves no doubt about the importance of the sixteenth president and the Union that he, more than anyone else, preserved. The steps that visitors must climb to enter the monument prepare them for what they find within: an immense, melancholy statue of the Great Emancipator, bracketed by the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Addressmajestic phrases that explain the meaning of the greatest blood sacrifice in American history. But the Vietnam Memorial makes no such unmistakable statement. We do not climb to meet this monument or even look up; we merely walk along a gradually descending path beside a polished granite wall. The only words inscribed on the stone are the names of 58,000 American women and men who gave their lives between 1959 and 1975, in the longest war the United States has ever fought.

As we walk, the black wall seems to rise beside us, as if thrust from the earth by the columns of names that lengthen on its face. The roll of the dead begins almost imperceptibly at ground level, then rises inexorablywaist height, shoulder height, head height, higheruntil at the monuments center the names of the dead hang over us with an almost unbearable weight of sadness. Here we are left to draw our own conclusions by a monument that does not presume to instruct us on the meaning of the deaths to which it bears witness. And here, at the turning of the path where the twin walls join, we pause, as so many do, to look back.

Because it is winter, the colonnade of Lincolns Greek temple looms white through the screen of trunks and bare branches, and it is suddenly clear that the narrowing V of the wall has been sited precisely to direct our gaze upward to the Memorial and to the hillside crosses of Arlington National Cemetery beyond. Turning again and looking up the path, it also becomes apparent that the oblique angle at which the walls join is not merely the product of Maya Lins superb aesthetic sense: the black arrow of the wall ahead points directly toward the marble shaft of the Washington Monument.

Here, surrounded by wars laid up in stone, the questions press in on us. Why this location, half in seclusion apart from the center of the Mall? Why this orientation, directing our attention toward the two great monuments that define the Malls long axis? Why, for that matter, should the Korean War Memorialless powerful emotionally but still evocative in its depiction of a rifle squad moving out, laden with combat gearhave been located in the counterpart space on the opposite flank of the Lincoln Memorial? And why, finally, do the facing halves of the new World War II monument bestride the Mall at the head of the Reflecting Pool, claiming a place as central as Washingtons obelisk and Lincolns Doric shrine?

Silent though their stones may be, the monuments on the Mall speak unmistakably to Americans about the relationships between, and the relative importance of, five warsthe Revolution, the Civil War, the Korean Conflict, the Vietnam War, and World War II. Even stronger implicit messages can be discerned in the absence of monuments commemorating other conflicts: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, numerous military interventions in the Caribbean and beyond, and three dozen or more Indian wars by which the citizens of the Republic appropriated lands that native peoples had called home for a thousand generations. All these messages are rooted in a commonly accepted grand narrative of American history, a story so familiar that the meanings of the memorials can be deciphered by almost any citizen who has had the benefit of a public school education.