First published in Great Britain in 2003 by

LEO COOPER

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books

47 Church Street,

Barnsley,

South Yorkshire,

S70 2AS

Copyright by Bernard Ireland 2003

ISBN 0 84415 001 1

ISBN 9781783379705 (epub)

ISBN 9781783379507 (prc)

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Burley-in-Wharfedale, West Yorkshire

Printed in England by CPI UK

Contents

Introduction

During the First World War German submarines destroyed 11.1 million gross registered tons of Allied and neutral merchant shipping. A quarter-century later they returned to sink a further 14.7 million tons. By far the greater proportion of these totals represent British ships, most of them lost in Atlantic waters.

It has been remarked probably far too often that a nation heedless of its history is doomed to repeat it. Nonetheless, if proof were ever needed of the underlying truth of this assertion, the Battle of the Atlantic provides it.

Peacetime democracies, by their very nature, prefer to devote ever-scarce financial resources to the direct benefit of the public rather than to pay the stiff premium demanded by an adequate defence. Like the imprudent householder who neglects necessary insurance, however, that public is very exposed when the roof is blown off.

Governments are notoriously short-termist, rarely looking beyond the next election, but there is, or certainly was in this case, little excuse for the professional armed forces compounding failure through poor strategic planning.

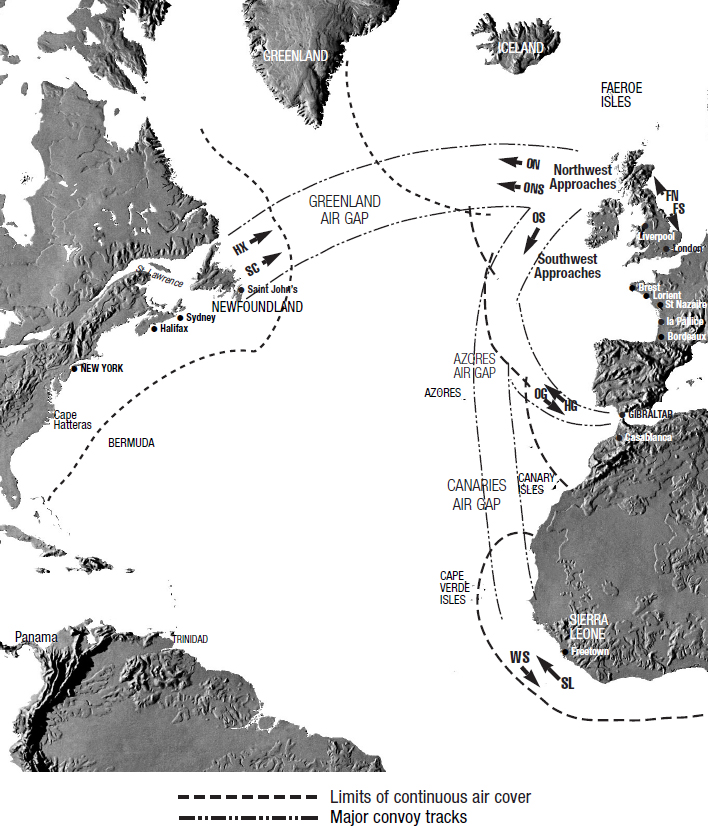

The First World War had already demonstrated the benefit of air cover for convoys yet maritime cooperation, a highly specialized aviation skill, was lumped in with all other aspects of flying as part of the remit for the new unified air force. The results, of naval laissez-faire as much as air force ambition, were inadequate numbers of the wrong aircraft, inadequately trained and deploying inadequate weapons.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, their representatives had found the British Admiralty despairing of its chances of beating the U-boat menace.

The urgent need, they discovered, was not of capital ships, but for huge numbers of flotilla vessels. Yet, came the peace, these same craft were among the first to be discarded. Big guns retained their glamour, offering the surest path to professional success. Between the wars, neither of the major fleets conducted the regular and realistic exercises that would have highlighted the continuing need for adequate numbers of ocean-going, specialist anti-submarine escorts.

In 1939, therefore, history repeated itself as the slaughter of helpless shipping began again. In 1914 there had been some excuse, for the success of the U-boat as commerce destroyer had proved as much a surprise to the Germans as it had to the British. Twenty-five years later there could be no such excuse. Ships protect, protocols do not.

Until mid-1943 the Admiralty again radiated an overwhelming sense of crisis, that again the nation might go under for loss of its merchant marine. Statistics show, however, that the Royal Navy's, little ships were performing so effectively that by Admiral Dnitz' own yardstick tonnage sunk per U-boat per day his force's success was already in decline by the latter half of 1941, its rate of sinking inadequate to destroy British-controlled shipping within his prescribed timescale.

That this trend was brutally reversed during 1942, after the United States became a belligerent, only served to illuminate similar deficiencies on the other side of the pond.

The sense of crisis long persisted, yet building rates for replacement Allied shipping quite quickly outstripped losses, and by an ever-increasing margin. Doubtless the still-lengthening toll of merchantmen engendered a degree of genuine pessimism in Britain, but the statistics suggest that there was also a degree of politicking involved, to impress upon the United States the need to bolster the British war effort. It is hoped that this narrative gives a balanced view.

Bernard Ireland

Fareham 2002

Chapter One

The Background

As, in the late sixteenth century, Spanish adventurers opened up Central and South America to conquest and colonization, their nation was locked in dispute with England. Religious differences were responsible for a continuous state of quasi-war, hostilities financed and sustained through the wealth that flowed back in the holds of the periodic flota and the individual great ships coming up from the Isthmus.

Elizabeth I of England was resourceful, but presided over an impoverished Treasury. To prey on Spanish trade offered the chance of both striking at Spain's ability to fight and the prospect of national (and personal) enrichment.

Of the fighting ships with which the Queen faced the enemy, less than twenty per cent were the property of the Crown. The remainder were owned and equipped by merchant adventurers, patriotic but with an eye to profitable return. Their inducement was the Letter of Marque, issued by the Crown to its captains to legitimize their activities. As they sailed private ships, they became known as privateers.

Letters of Marque were no new device, having been issued as far back as 1243 for the annoyance of the King's enemies. Ships taken by privateers had, by international law, to be taken to the nearest port at which they could be condemned by a Prize Court, valued and sold off. The income would be split in agreed proportion between Crown and privateer captain, the welfare of crew and passengers of the prize having been observed.

In reality, unfortunately, it was risky and time-consuming to bring a prize to port. Far simpler for her to disappear with all hands. In short, there was always incentive for privateering to degenerate into something akin to common piracy, being frequently rewarded accordingly and summarily at the end of a convenient yardarm.

Usually profitable, occasionally hugely so, privateering was exceedingly widespread. Even as Elizabeth issued her own licences, for instance, others of her honest seafarers were being persecuted in the near seas by men of like persuasion from the provinces of Holland and Zeeland, under the pretext that English merchants were assisting Dunkerque, Spain and Antwerp.

As west-European maritime powers founded and extended their empires, trade increased and, with it, rivalries that led often to war. To the detriment of recruitment to the regular services English, French or Dutch the best and most enterprising seamen were immediately drawn by the undoubted glamour and potential of privateering.

By the eighteenth century, the Royal Navy operated scores of minor warships in an effort to counter the activities of privateers. Sloops, brigs, cutters and, later, schooners, they offered superb experience for their commanders and lieutenants-in-command. While many enjoyed individual success however, their overall activities were not well directed.

In the course of the unnecessary War of 1812 British trade endured some very enterprising American privateering. Over five hundred American Letters of Marque were authorized, these taking some 1,300 British merchantmen. This effort would not, of itself, have won a war against a major maritime power, but each capture aided the enemy and racked up insurance rates a further notch.

The so-called Crimean War was terminated by plenipotentiaries who, gathering in Paris in 1856, also made a declaration outlawing the practice of privateering. Powers including Great Britain, France, Russia, Austria and Prussia, later joined by others, agreed the following fundamental points:

Next page