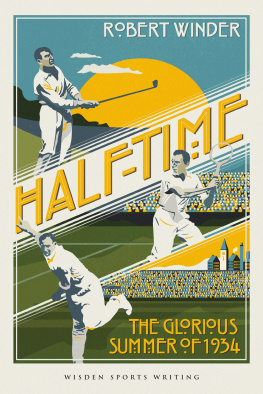

Half-Time

The Little Wonder: The Remarkable History of Wisden

Hell for Leather: A Modern Cricket Journey

Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain

Half-Time

The Glorious Summer of 1934

Robert Winder

John Wisden & Co Ltd

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

London | New York |

WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

www.wisden.com

www.wisdenrecords.com

Follow Wisden on Twitter @WisdenAlmanack

and on Facebook at Wisden Sports

WISDEN and the wood-engraving device are trademarks of John Wisden & Company Ltd, a subsidiary of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

Robert Winder 2015

Robert Winder has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organisation acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4729-0892-6

ePub: 978-1-4729-0893-3

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.wisden.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

For Mary and Jim Winder

Contents

There was a moment, when Lee Westwood stood on the seventh tee at Muirfield, near Edinburgh, on 21 July 2013, when it seemed as though a sporting miracle might be at hand. It was a roasting hot afternoon and, as the Englishman waited for Tiger Woods and Adam Scott to clear the green up ahead, he tried to gauge the strength of the wind. He was a third of the way through the final round of the Open; the thermometer was touching 30 degrees; and a birdie at the previous hole had given him a heart-stopping three-shot lead. His first major win could be just a few smooth swings away.

The salty grass, stiffened by spray from the North Sea, was wispy and scorched, the humps and hillocks were dry as hay, and the atmosphere shook with expectation. The sun-drenched gallery sported shorts and dark glasses in place of the usual waterproofs and umbrellas, and the main thing the spectators had to worry about, as they tilted their heads to watch white balls arching into blue sky, was the sunburn on their necks.

Most British sports fans, barring the odd Scot dismayed by the prospect of an English success story, had to pinch themselves, because a Westwood win was only one of three momentous possibilities jostling for headline space that day. Down in north London, Englands cricketers (boosted by an innings of 178 by a young Yorkshireman, Joe Root) were crushing Australia at Lords, a feat they had managed only once once in the entire 20th century. And further south Chris Froome was sipping iced bubbly as he pedalled his way up the Champs-Elyses to give Britain its second straight winner of the Tour de France. There was a carnival spirit shimmering in the freakishly hot air.

It was only a year since the bright, champagne-cork summer of 2012, when Bradley Wigginss victory in the Tour de France (the first by a Briton) and the gold rush of the London Olympics had put a smile on Britains sometimes grumpy face. Now, in the bewildering space of a single day, it was happening all over again. A few weeks earlier Justin Rose had become the first Englishman to win the US Open since Tony Jacklin in 1970; and the British and Irish Lions had roused themselves to beat Australia. And in early July an even bigger giant had been slain when Andy Murray ended Britains 77-year wait for a male Wimbledon champion by beating the seemingly indestructible Novak Djokovic. The following morning he posed for photographs at the feet of Fred Perry, whose statue stands in the grounds of the All England Club, marking the last occasion, seven and a half decades earlier, when a home champion had lifted the trophy.

It didnt matter that Murray had won 1.6 million, whereas Perry won nothing apart from a silver cup. Nor did we care that h e w as Scottish, that three English cricketers (Pietersen, Prior and Trott) were from the southern hemisphere, or that Froome was hailing his Tour de France victory as a great day for Africa. Such was modern sport, and modern migratory life. If Westwood held his nerve it would surely brush gilt on one of the more remarkable clean sweeps ever seen in sport.

It wasnt to be. In front of his 12-year-old son, who was in the gallery, Westwood fidgeted over his club selection before making a bizarre (and in retrospect rash) attempt to fly a nine-iron 200 yards. Perhaps he was fired by the memories of the very same afternoon four years earlier, when he bogeyed three of the last four holes in the 2009 Open at Turnberry to miss out on a playoff by one stroke. Either way, it was risky.

It doesnt sound plausible that a whole life can change while a golf ball hangs in the air, suspended above a sea of upturned faces. But something like that happened when Westwood, with that distinctively bowed front arm of his, thumped down through his tee shot, firing the ball high into the blue haze. Convention demanded that, a few brief seconds later, it would thud down into the green, drawing a shout of approval from the gallery; but this was not a conventional moment. At the summit of its flight it seemed to stall and lose momentum; then it plummeted like a spent firework into the bunker that guarded the front. Westwoods Open dream crashed into the sand with it. Phil Mickelson was halfway through one of the great rounds of his life, and two hours later the famous silver claret jug had once more been dashed from the Englishmans lips.

But this was only a blip it could hardly dampen the burst of euphoric flag-waving inspired by this astonishing weekend. Up and down the land, channel-hopping couch potatoes watched the pageant unfold and became punch-drunk, even confused, by all this success. Was that Froome grimacing at his tricky lie in the sand? Was that Luke Donald clinging on to a catch in the gully? Was that Stuart Broad juddering up the Champs-Elyses in a buttercup jersey? When it emerged that the Royal and Ancient was blaming the relatively modest crowd at Muirfield on the improbably hot weather, it added a further dimension of unreality to the weekends events everyone knew that the Open was supposed to be played under grey skies, and in gale-force drizzle.

It seemed no less than the occasion demanded that Prince George, the royal baby-in-waiting who had been keeping the worlds media camped outside a London hospital for a week or more, should choose this golden moment the day after Super-Sunday to come into the world. It added royal glamour to the national rejoicing, and the papers led the cheers. A tour de force for British sport, cried the Independent . How weve become a nation of winners, trumpeted the Daily Mail . Even the Financial Times gave a nod of approval: Britain misses the treble, it observed. But not a bad afternoon.