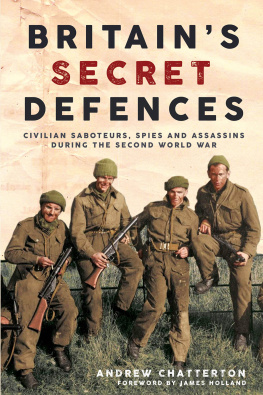

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2022 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

and

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

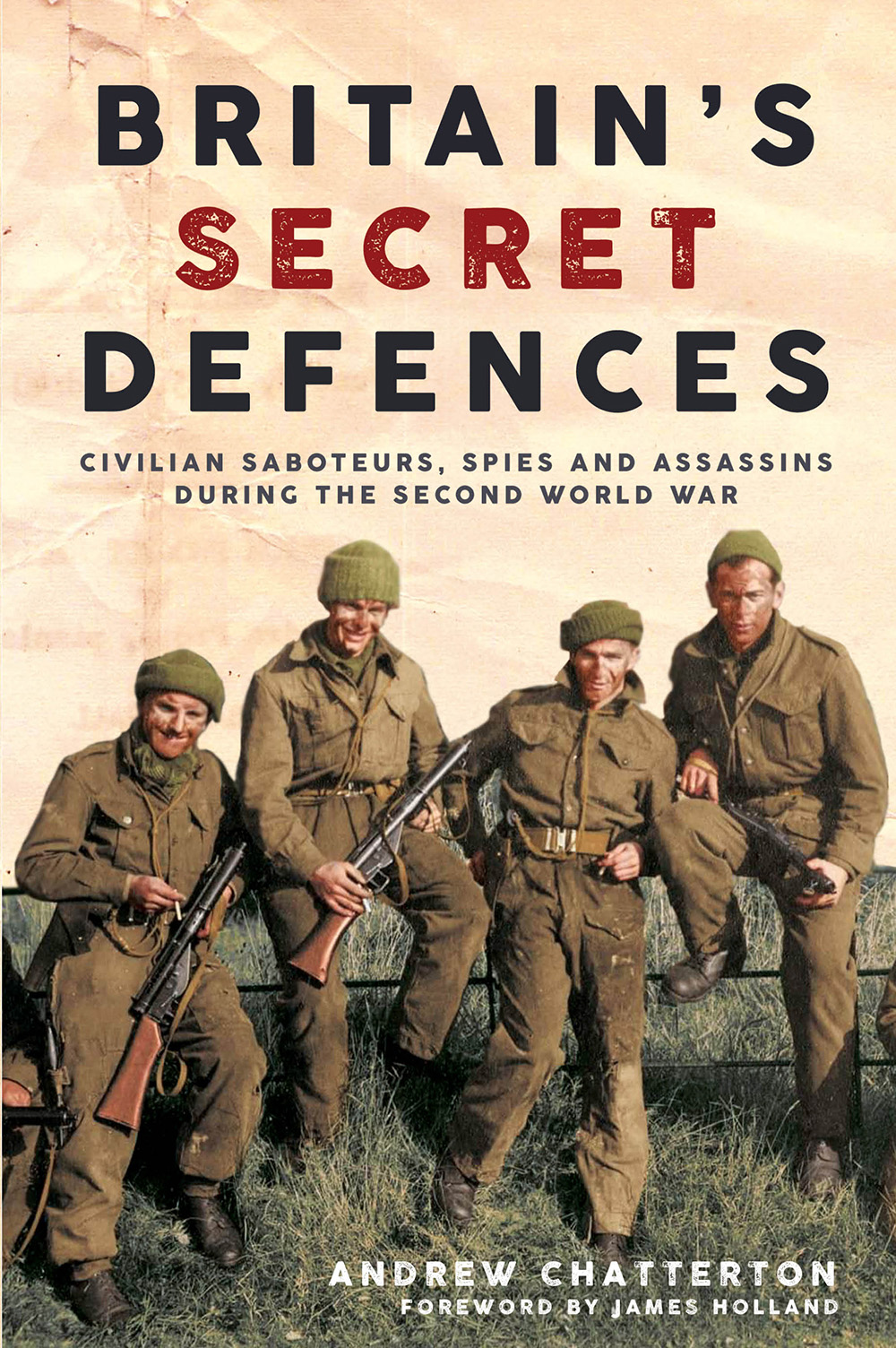

Copyright 2022 Andrew Chatterton

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-100-5

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-101-2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ Books

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

Contents

Foreword

Its really quite remarkable to think that Britain was the only country in the Second World War to prepare a secret guerrilla and resistance movement before any enemy invasion had actually taken place. Nor did the enemy ever attempt to cross the English Channel. But in the summer of 1940 there were plenty of people who were convinced the threat of a German invasion was a very real one. Take Norman Field, for example, a young officer in the Royal Fusiliers, who had been wounded in the hand in France in May 1940 and was subsequently evacuated from Dunkirk. Despite his wound, he was itching to get back into action. God almighty! he told me. To think those bloody Germans were going to come here! So, I asked him, you really thought they were going to invade? Yes, he replied, and so did everyone else.

Of course, we now know what happened: that the RAF kept the Luftwaffe at bay, that the Royal Navy would have seen off any attempted German invasion in any case, that Germany then turned to the Soviet Union before it was ready and that the democracies, with their global reach, access to the worlds resources and industrial muscle, were, along with the USSR, able to gradually grind down the Germans and defeat them five long years later. But men like Norman Field had no crystal ball and despite Britains many advantages, both in terms of geography and material wealth, the strategic earthquake of the fall of France and the defeat of the British Expeditionary Force was such that an invasion of Britain by Nazi Germany really did seem both a very real threat and a highly probable one too. After all, France was, in modern terminology, a superpower with a vast army and yet it had fallen in just six weeks. Britain had the worlds largest navy and merchant navy, a huge empire and immense global reach, but its army was small and had been defeated and humiliated, its weapons and equipment left on the sands of Dunkirk. This island nation, for all its assets, felt weakened, exposed and extremely vulnerable.

It was because of the dramatic events on the continent and the defeat of France had seemed inevitable after just a few days of the German attack that Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, announced the immediate formation of the voluntary Local Defence Volunteers on 14 May 1940; if ever a decision demonstrated the profound shock and concern of the new Churchill government at events across the Channel, it was this: the raising of a volunteer army to defend Britains shores in the event of an enemy invasion.

A few weeks later, after his return to England and having been discharged from hospital, Norman Field was recuperating at his mother and step-fathers house in Ilminster, Somerset when he was visited by Peter Wilkinson, a friend and fellow officer in the Royal Fusiliers. Field had always suspected that Wilkinson was also working for the Secret Intelligence Service in some capacity; before the German attack had been launched on 10 May 1940, his friend had on occasion mysteriously absented himself from the battalion on various courses and assignments. Neither Field nor his fellow officers had ever pressed Wilkinson about what he was up to one simply didnt but with defeat on the continent and Nazi Germany seemingly unstoppable, Field wanted to get an active post quickly and thought Wilkinson might be able to help.

Peter, he said to him, I dont know what youre doing and Im not going to ask, but whatever it is, if there might be any opportunities for me, please do bear me in mind. Wilkinson said nothing there wasnt even a flicker of a response in his eye but two days later, a telegram arrived asking Field to report to a place called Coleshill in Berkshire for an interview.

He duly reported as bidden and after waiting in a vast servants hall, a small middle-aged man with a trim moustache appeared, introduced himself as Colonel Colin Gubbins, and told Field he had been given the job of setting up a top-secret underground operation in Britain to help deal with an invasion if and when it happened. The Auxiliary Units, as they were deliberately vaguely called, were a further organisation set up in the wake of the French defeat and threat of invasion. Not the Home Guard, but, as Andrew Chatterton describes it, a highly trained, ruthless, secret sabotage and guerrilla force. Was Field prepared to join this organisation, Gubbins asked him? Yes, he replied, without hesitation, although had to admit he had still to be declared medically fit. This, Gubbins, assured him, was no impediment. Sure enough, within a couple of days, Field was sent for a special medical and immediately declared fit.

Even better, he was told he was skipping two ranks and being made a captain in the Auxiliary Units, a top-secret organisation. A few days later, he was sent to The Garth in Kent, where he was to become the intelligence officer for a key operational area and taking over command from Peter Fleming, brother of the Bond novelist Ian Fleming. In fact, it was Peter who was the better known at the time. A Guards officer and a highly renowned explorer, adventurer and author, he had been one of the brains behind the Auxiliary Units. It needed people with flair, drive, intelligence and imagination, characteristics Fleming had in abundance.

The Garth was a secluded farmhouse in the quiet village of Bilting, Kent. It was, perhaps, only natural that Kent should be one of the first places to recruit Auxiliary Units as it was the county closest to occupied France. Requisitioned by the army, it became the first regional training centre under Fleming. The growth of the Auxiliary Units meant Fleming was needed elsewhere and so Field was to shadow him for a fortnight and then take over.

What followed over Fields time at The Garth was the further growth of this extraordinary organisation, one in which secrecy and ingenuity were key watchwords. Everyone who joined had to sign the Official Secrets Act; they could not even tell their wives or closest family they were members. It was, and remained, an entirely deniable organisation, and until the end of the war and beyond, no one, other than those involved, knew of its existence. Recruits were warned that should the invasion come, it would more than likely become a suicide mission. Cyanide pills were to be swallowed if capture looked certain. Ingenuity was key. Teams of eight men would operate together and, should an invasion occur, would base themselves in a hidden underground bunker equipped with supplies of food, weapons and ammunition to last a fortnight. How to hide the entrances to these bunkers prompted even greater imagination and ingenuity; Field devised an entranceway, for example, that was disguised as a sheep trough. Others were accessed through an outside privy.

Next page