This electronic edition published 2013

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire

GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Bernard OConnor 2009, 2013

ISBN 9781445611549 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445611785 (e-BOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

Foreword

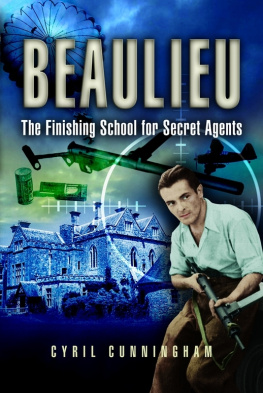

I had never heard of Brickendonbury until I moved to Everton, a small village about halfway between Cambridge and Bedford. When I discovered that there was a Second World War airfield at the bottom of the hill (66 m) where I used to take my dog for walks, I asked about it in the Thornton Arms, the local pub. I was told that there was a gentleman in the village who had worked there during the war. Calling to see him, I asked if he could tell me anything about what went on at the airfield. He refused, arguing that he had signed the Official Secrets Act. Intrigued, I spent the next decade or so researching its history and publishing a number of books, the first being RAF Tempsford: Churchills Most Secret Airfield. Two Special Duties squadrons were based there, flying off during the nights on either side of the full moon to drop tens of thousands of tons of supplies to resistance groups in countries across occupied Western Europe, parachuting over 2,000 agents and undertaking landing and pick-up operations in France.

Researching the stories of the women agents who were flown out, I necessarily found out about their training. Newspapers, magazines, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, military histories, websites and recently released documents in the National Archives led me to publish Churchills Angels.

Often being asked to give talks on the subject, I created a number of presentations, one of which was on the buildings requisitioned by the Special Operations Executive, a top-secret intelligence organisation during the war, where agents were trained in various aspects of clandestine warfare. I found evidence that over a thousand British and overseas personnel attended an industrial sabotage course at Brickendonbury Manor, near Hertford, about 20 miles north of London. Sparked by my commissioning editor to write another book, I undertook to research its history and the important role it played during the Second World War.

I need to acknowledge the work already done by Roderick Bailey, John Charrot, Freddie Clark, Igor Cornelissen, Bickham Sweet-Escott, Michael Foot, William Mackenzie, Sam McBride, Ray Mears, Russell Miller, Neil Rees, Jeffery Richelson, David Stafford, Des Turner, Ian Valentine and Hugh Verity, whose academic research has shed light on the events that follow. The National Archives online catalogue allowed me to identify relevant documents and the staff there very kindly provided access to recently released correspondence and mission papers related to personnel in the Special Operations Executive. Kristina Lawson, Head of Market Information and Promotion at Brickendonbury, kindly provided photographs and details of the houses history. Rich Duckett helped locate George Rheams notes on Brickendonbury. The Sandy and Potton library staff was very helpful in locating out-of-county books and articles from academic journals. Bonnie West, Senior Archive/Library Assistant at Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies, helped locate newspaper and journal articles. Hydro Vemork, Rjukan, kindly provided photographs of the heavy water plant; Mrs John Clarke of Nobby Clarke; and Sam McBride of Frederick Peters. Steven Kippax needs special thanks. Not only was he able to locate and copy numerous personnel files, but he and members of the Special Operations Executive user group on yahoo.com have provided answers to my many queries and stimulated further research.

CHAPTER 1

Brickendonbury Manors History until the Start of the Second World War, September 1939

Various books, journals and websites have detailed the history of the house and its gardens but few refer to its role during the Second World War. How long a house has stood on the site is unknown. While prehistoric people may have wandered through the nearby forested countryside, there is no evidence of an occupation site. Ermine Street, the Roman road from London to York, runs along the eastern boundary of the parish about half a mile away. During drainage work on the moat in 1893, 430 Roman coins, dated to about AD 250, were unearthed. Maybe they were hidden by someone worried about an attack, who then failed to return and recover them.

Hertford, an Anglo-Saxon settlement first recorded in 673, lies on the crossing point on the River Lea, about 2 miles to the north. Brickendon is also Anglo-Saxon, thought to mean Bricas hill. It would have been an advantageous site with a 72-metre promontory overlooking the wooded valley of Brickendon Brook to the south and west, the gently rising Hertford Heath to the east and a ridge and valley stretching down to the River Lea in the north.

Although the site is thought to have been occupied continuously since Saxon times, who owned the estate before 1016 is unknown. At that time it belonged to the canons of nearby Waltham Abbey, acknowledged by Edward the Confessor in 1061 and King Harold II shortly before the Norman Conquest. It is thought that, following the tradition of other landowners from northern France, a manor house was erected on the site and a moat constructed. The addition of the suffix -bury indicates a fortified site. A moat was constructed, not for defence, more as a source of fish for Fridays and throughout the forty days of Lent when everyone was expected not to eat meat.

King Henry II, following the murder of Thomas Becket in 1170, granted the Liberty of Brickendon to the abbey as part of his penance. When Henry VIII broke with Rome, Waltham Abbey, like the monasteries, was dissolved; the estate was sold to Thomas Knighton in 1542. After Knighton sold it to Edmond Allen, in 1588 it was purchased by Stephen and his son William Soame or Soames for 1,000.

The present-day mansion dates back to about 1690 following Edward Clarke purchasing the estate in 1682 from the Soames family. Clarke was a Leicestershire merchant who, following the custom of those days, bought himself a large estate in pleasant countryside away from the noisy, dirty and overcrowded City of London. He moved to the capital after the Plague and Great Fire. Knighted in 1689, between 1690 and 1691 he was master of the Merchant Taylors Company, and in 1696 Lord Mayor of London. He paid for a large, imposing mansion to be built on the site of the old manor house and, over successive generations, the house was extended and it was acquired through marriage by the Morgan family in the early eighteenth century. Charles Morgan was the Judge Advocate General and Judge Martial of Queen Annes forces. Little did he know that his estate would be used for military training over 200 years later. His family were responsible for planting the avenue of trees, known as Morgans Walk, which connects the mansion with Hertford.

In the late nineteenth century the estate was leased or let to a series of tenants, among them Russell Ellice, a director of the East India Company and its chairman in 1853. His ownership created the estates first link with South East Asia.