PREFACE

This is a new sort of course book for students and teachers interested in understanding the origins of the modern West. It is new because until very recently both scholars and the broader public have assumed that the West and modernity were phenomena that grew directly out of the cultures and societies of western Europe, and in particular, Britain, France, Germany, and the north of Italy. These were seen as the epicenters of the developments that gave shape to the modern West: first of all, the Hellenized Roman Empire, and then after the long parenthesis of the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, the Reformation, the emergence of the nation-state, and eventually representative, constitutional democracy and the free-market economy. The past was imagined as a progression, whether guided by God or some imprecise Providence, out of primitivism and barbarity toward some ever-more perfect future. This is not so surprising, perhaps, when one considers that until recently our world has been dominated by these countries and their colonial heirs in the Anglo-American world, and that both the scholars who created this narrative, and the students who assimilated it, were natives of these nation-states, and identified in an intuitive and largely uncritical way with their values. It is a narrative that in retrospect could easily seem to be obviously true and was immensely appealing and self-validating. It was a narrative ground in presumptions, both historical and moral.

However, both society and scholarship have changed. The Anglo-European world can no longer presume to represent the end of history, and, in any case, that same Anglo-European world is now made up of persons of diverse origins, genders, cultural backgrounds, and religious orientations, all of whom play crucially important roles in society and history. Indeed, this has long been the case; however, history was generally studied from the narrow perspective of upper-class white Christian men (and to a lesser extent, women), and the role of other groups was downplayed or dismisseda historical exercise now dismissed as one focusing on Dead White Men. But such a bias is not surprising, given that until the twentieth century power and prestige within both the academy and society as a whole lay largely in the hands of a narrow, privileged group of economically advantaged Christian European males. But, today, both the academy and society have been transformed, as men and women of diverse cultural, social, and ethnic backgrounds have become full participants in the scholarly enterprisea fact reflected in the new demographic diversity of both scholars and students. Consequently, over the last half century or so, the way we do history has changed. Historical populations previously thought of as irrelevant to the grand narrative of Western civilizationpeasants, the poor, women, Jews, and Muslims, to name a fewhave become recognized as legitimate and important objects of study, whose role in the development of the modern world must be understood. This alone should be enough to provoke a reconsideration of how we conceive of and teach the development of Western society and culture, but there are other reasons, no less compelling, to do so. First among these, perhaps, is the realization that the paradigm of the nation-state is simply not an appropriate framework for the study of the premodern period. European nationalism did not coalesce as a mode of identity until the nineteenth century, and it only emerged as an apparently valid historical category when scholars whether deliberately or unconsciouslysuppressed aspects of the past that appeared not to validate it and imposed anachronistic perspectives on the evidence they chose to use. Whereas previously, historians focused primarily on the writings and artistic expressions of the elite, they now also explore other sourcestax records, court and inquisition transcripts, objects of daily use, irrigation systems, folk literature and traditions, and so onthat were previously ignored or neglected because they did not seem likely to yield information relating to the history of great men and the national values these were believed to embody. New data, new technology, and new perspectives employed by historians and scholars of art, literature, and philosophy have led to serious reconsiderations of what constitutes the building blocks of our history, and in particular the value of the paradigm of the nation-state, for the period prior to the nineteenth century.

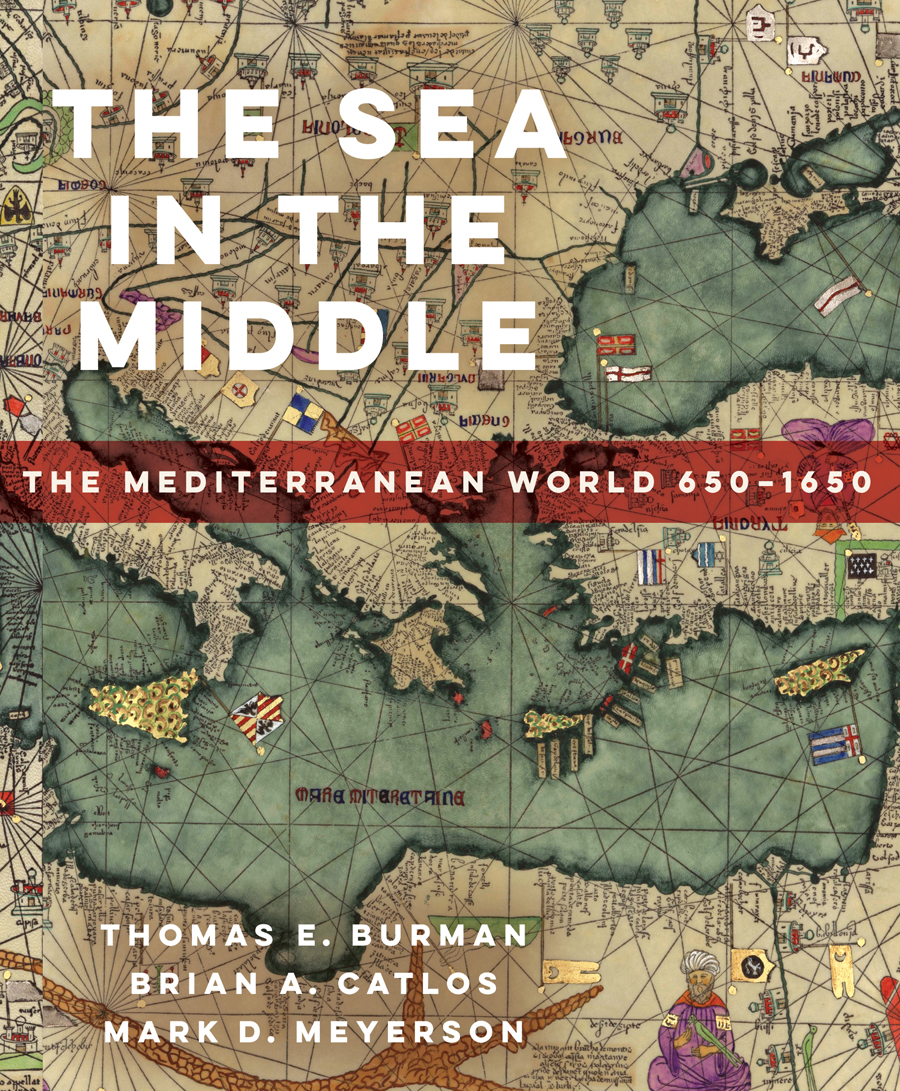

Other categorical distinctions that have been long presumed to be fundamental and undeniableEurope versus Africa and Asia, the Occident versus the Orient, Christian culture as opposed to Jewish and Islamic cultures, North versus Southhave now been revealed to be if not ephemeral, at the very least, contextual, subjective, and relative in nature. Indeed, the very notion of the West has evolved, and for the purposes of this book, it will refer in broadest terms to the cultures and societies stretching west from the Indus to the Atlantic and from sub-Saharan Africa to the Balticthose shaped by what might be referred to as Persian-Abrahamic religion. And this brings us to the Mediterranean.

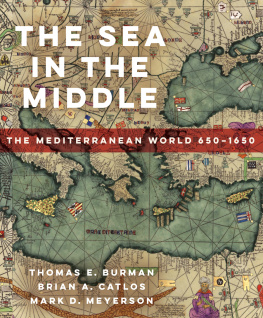

Mediterranean Studies and Studying the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean is, of course, where Africa, Asia, and Europe meet, the sea around which the Roman Empire was once arrayed, and the region in which the Christian, Jewish, and Islamic worlds intersected and overlapped. Until the last few decades, this is how most scholars of history saw it. In the mid-twentieth century, however, a few historians, notably Shlomo Goitein, the pioneer of geniza studies, and Fernand Braudel, an early environmental historian, began to study the region in its own right. Braudels work was immediately influential in the development of Atlantic studies, a field that built upon the notion that a body of water, rather than a body of land, can frame a broad and meaningful historical analysis. For us, the authors of this book, the Mediterranean is not merely the sea, nor the islands and coast that surround it. It is a region , and like any regionit is an area bound by common features and characteristics, rather than a formally constituted and clearly defined zone. It has no borders that demarcate it. Rather than end at a definite point, the Mediterranean world fades, as it were, the farther one gets from its center. In any case, the precise way in which Mediterranean is defined in any scholarly exercise depends on the context one is considering, and the characteristics one is focusing on. For Braudel it may have been region of the vine and the olive, but it was much more. Thus, as the reader will see, our Mediterranean can include both the Middle East and Portugal, the Black and Red Seas, and trails off into central Africa, northern Europe, and Central Asia. In other words, the Mediterranean for us is not a thing, not a unity. Rather, it represents a whole spectrum of overlapping modes of identity, action, and expression in history, and of perspectives for understanding the history of the medieval world.