For my parents,

Beilin Woo Zia and Yee Chen Zia,

And for the next generation:

Henry Dewey, Jr., Jennifer Camille, Frank Alexander, Emily Shizue, Beilin Elizabeth, Rory Hajime, Grayson Alan, Marshall Teckyi, Madelaine Zia, Mitchell Teck-zhang, and Devon Zia. Also Jarrin Kainoa, Erin Joy, Maya Jialin, Kazumi Okahara, Masami Okahara, Alexander Tadashi, Maya Anne Sachie, Nicholas Akai, and Peter Wen

I n the early 1980s, a song entitled Turning Japanese jumped to the top of the charts and instantly thrust an otherwise obscure British group, The Vapors, into the limelight. New Wavers rocked to the musings of a singer who thinks he might be turning Japanese. Though many dancers added the quaint touch of pulling their eyelids taut as they pogoed to the beat, the song had nothing to do with becoming Japanese or Asian.

As an Asian American, I was intrigued by the notion that you could turn into or adopt another culture so vastly different from your own, and that you would be conscious of this transformation as it took place. When Turning Japanese was at the height of popularity, America was in the midst of a crushing depression that began with the collapse of the auto industry. Intense Japan-bashing characterized the times, and Asian Americans, too, came under fire. The song prompted me to ask, What about Turning American?

It was the same question that many of the 10 million Asian Americans have been asking with increasing frequency in the last years of the twentieth century, an era marked by significant challenges and progress for us. But one question hadnt changed. Asian Americans were still wondering out loud, among ourselves and in public discourse, What does it take to become American?

The spirit of the question is not about the mechanics of becoming American, a process with which we are familiar: involving ourselves in our communities, gaining citizenship, participating in the political process by getting the vote out, running for office, and, yes, donating to campaigns. Nor is it about getting acculturatedmost of us have been Americans plenty long enough to walk the talk and traverse the nuances of the rhyme, rhythm, and soul of this culture.

What weve really been wanting to know is how to become accepted as Americans. For if baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and Chevrolet were enough for us to gain acceptance as Americans,then there would be no periodic refrain about alien Asian spies, no persistent bewilderment toward us as strange and exotic characters, no cries of foul play by Asian Americans, and no need for this book.

Instead, Asian Americans have been caught in a time warp that, every decade or so, propels us back to the nineteenth century, when congressional hearings debated whether we were too corrupt, too untrustworthy, too uncouth to be Americans. Only in the late 1990s the discussion was about campaign donations and alleged espionage.

Missing from the tons of newsprint and miles of videotape in this most recent round were the heartwarming stories of my universe, the tales of valiant women and men of Asian ancestry who struggled and sacrificed to make contributions to their country, the United States of America, and who wished to be seen as full Americans. Ive been struck time and again by how little is really known about us and the America we are part of; how the rich textures of who we are, why we are here, and what we bring to America remain so absent from the picture.

But a community as large, diverse, and dynamic as the Asian American and Pacific Islander peoples cannot stay on the edge of obscurity, frustrated by images that have rendered us invisible and voiceless, while other American communities watch us and wonder why we are at the center of key issues of the day. This book was written with the hope of changing this condition. Its personal essays and broader chronicles reflect conversations and stories that Asian Americans tell one another, about the challenges weve met, the people weve encountered, and the lessons weve drawn. Its about the numerous and disparate Asian ethnicities that have come together in this land, evolving into an American people.

It is time for Asian Americans to open up our universe, to reveal our limitless energy and unbounded dreams, our hopes as well as our fears: to show what it means, at the dawn of a new century, for a people to be Turning American.

BEYOND OUR SHADOWS

From Nothing, a Consciousness

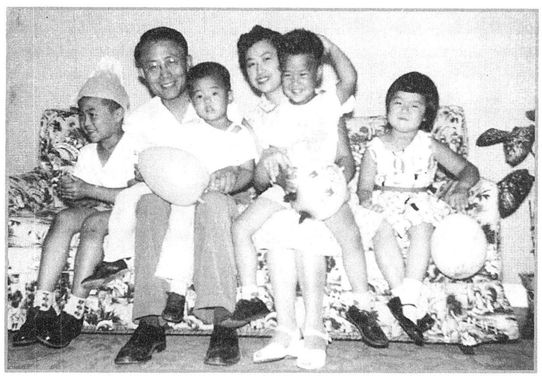

The Zia family in 1957: Dad and Mom with (left to right) Henry, Hugo, Hoyt, and the author

Little China doll, whats your name?

This question always made me feel awkward. I knew there was something unwholesome in being seen as a doll, and a fragile china one at that. But, taught to respect my elders at all times, I would answer dutifully, mumbling my name.

Zia, they would cluck and nod. It means aunt in Italian, you know?

To me, growing up in New Jersey, along the New York-Philadelphia axis, it seemed almost everyone was a little Italian, or at least had an Italian aunt.

One day in the early 1980s, the routine changed unexpectedly. I was introduced to a colleague, a newspaper editor. Making small talk, he said, Your name is very interesting I noted his Euro-Anglo heritage and braced myself for yet another Italian lesson.

Zia, hmm, he said. Are you Pakistani?

I nearly choked. For many people, Pakistan is not familiar geography. Inthose days it was inconceivable that a stranger might connect this South Asian, Pakistani name with my East Asian, Chinese face.

Through the unscientific process of converting Asian names into an alphabetic form, my romanized Chinese last name became identical to a common romanized Pakistani name. In fact, it was homonymous with a much despised ruler of Pakistan. Newspaper headlines about him read: President Zia Hated by Masses and Pakistanis Cry, Zia Must Go. Id clip out the headlines and send them to my siblings in jest. When President Zias plane mysteriously crashed, I grew wary. After years of being mistaken for Japanese and nearly every other East Asian ethnicity, I added Pakistani to my list.

I soon discovered this would be the first of many such incidents. Zia Maria began to give way to Mohammad Zia ul-Haq. A new awareness of Asian Americans was emerging.

T he abrupt change in my name ritual signaled my personal awakening to a modern-day American revolution in progress. In 1965, an immigration policy that had given racial preferences to Europeans for nearly two hundred years officially came to an end. Millions of new immigrants to America were no longer the standard vanilla but Hispanic, African, Caribbean, andmost dramatically for meAsian. Though I was intellectually aware of the explosive growth in my community, I hadnt yet adjusted my own sense of self, or the way I imagined other Americans viewed me.

Up until then, I was someone living in the shadows of American society, struggling to find some way into a portrait that was firmly etched in white and, occasionally, black. And there were plenty of reminders that I wasnt relevant. Like the voices of my 1960s high school friends Rose and Julie. Rose was black, and Julie was white. One day we stood in the school yard, talking about the civil rights movement swirling around us, about cities engulfed in flames and the dreams for justice and equality that burned in each of us.