A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF SPORT

VOLUME 2

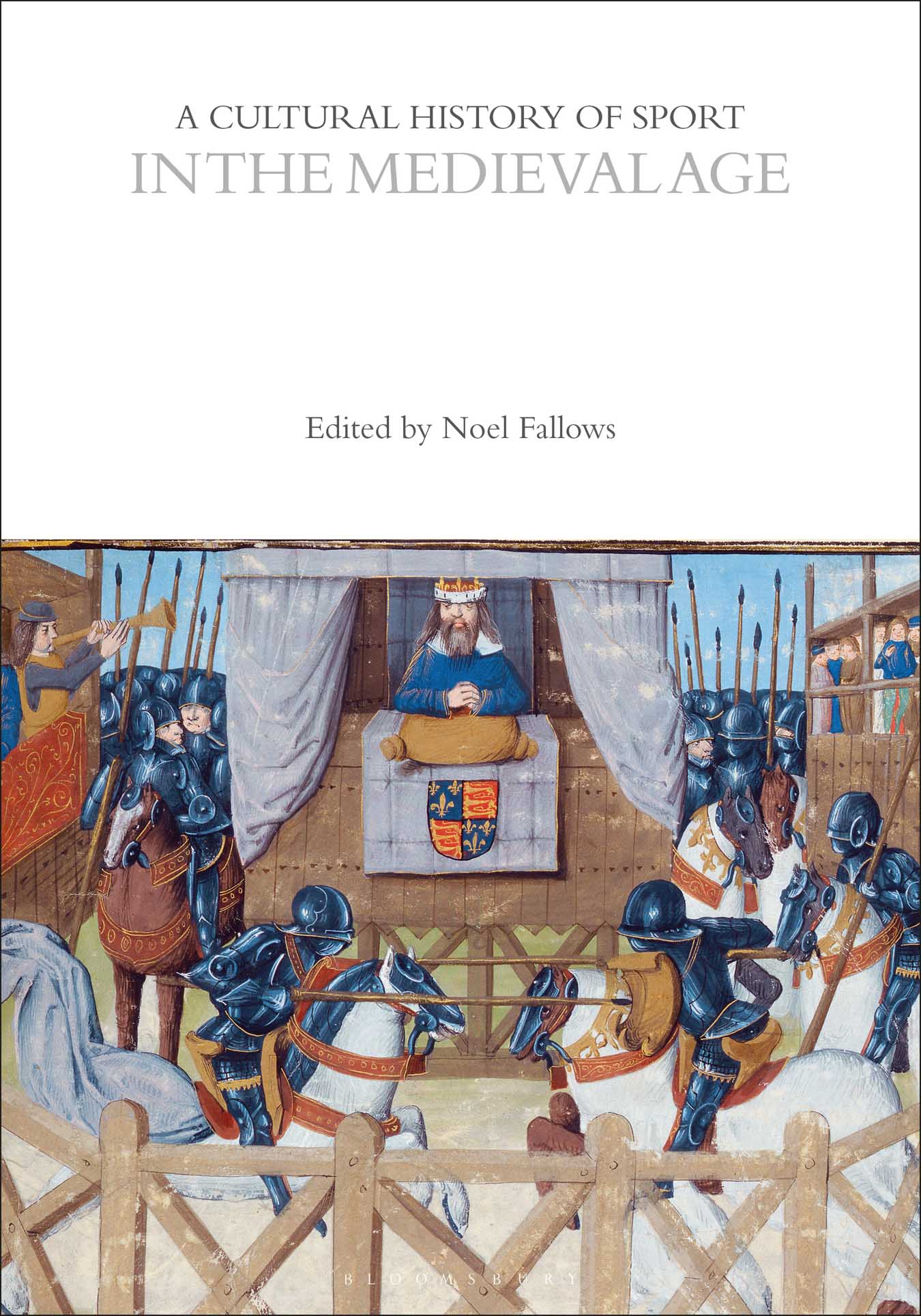

A Cultural History of Sport

General Editors: Wray Vamplew, John McClelland, and Mark Dyreson

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Sport in Antiquity

Edited by Paul Christesen and Charles Stocking

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Sport in the Medieval Age

Edited by Noel Fallows

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Sport in the Renaissance

Edited by Alessandro Arcangeli

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Sport in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Rebekka von Mallinckrodt

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Sport in the Age of Industry

Edited by Mike Huggins

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Sport in the Modern Age

Edited by Steven Riess

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

A Cultural History of Sport is a six-volume series reviewing the evolution of both the internal practices of sport from remote Antiquity to the present and the ways and degrees to which sport has reflectedand been integrated intocontemporary cultural criteria. All of the volumes are constructed in the same pattern, with an initial chapter outlining the purposes of sport during the time frame to which the volume is devoted. Seven chapters, each written by a specialist of the period, then deal in turn with time and space, equipment and technology, rules and order, conflict and accommodation, inclusion and segregation, athletes and identities, and representation. The reader therefore has the choice between synchronic and diachronic approaches, between concentrating on the diverse facets of sport in a single historical period, and exploring one or more of those facets as they evolved over time and became concretized in the practices and relations of the twenty-first century.

The six volumes cover the topic as follows:

Volume 1: A Cultural History of Sport in Antiquity (600 BCE 500 CE )

Volume 2: A Cultural History of Sport in the Middle Ages (5001450)

Volume 3: A Cultural History of Sport in the Early Modern Period (14501650)

Volume 4: A Cultural History of Sport in the Age of Enlightenment (16501800)

Volume 5: A Cultural History of Sport in the Age of Industry (18001920)

Volume 6: A Cultural History of Sport in the Modern Age (1920present)

General Editors:

Wray Vamplew, Emeritus Professor of Sports History, University of Stirling, UK, and Global Professorial Fellow, University of Edinburgh, UK

John McClelland, Professor Emeritus of French Literature and Sport History, University of Toronto, Canada.

Mark Dyreson, Professor of Kinesiology, Affiliate Professor of History, and Director of Research and Educational Programs for the Center for the Study of Sports and Society, Pennsylvania State University, USA

CRITICAL APPROACHES TO SPORT IN THE MEDIEVAL AGE

According to an anonymous Latin proverb: Spoken words fly away, written words remain (Verba volant, scripta manent). Looking back to the medieval age through the prism of the twenty-first century it is difficult to comment on physical activities such as sporting events, which happen in the moment in both time and space, without actually being able to see or hear them. However, the examination of concrete written, pictorial, and archaeological relics in a holistic way inevitably leads to the conclusion that there were indeed medieval sports. The main issue with many of the single-authored scholarly monographs on the subject is that the authors are almost forced into the position of using an inductive approach to the subject, a strategy that can be traced to the Dutch historian Johan Huizingas germinal book Homo Ludens (1938; trans. 1955). Huizingas theory can be distilled in the apothegm that play is the antithesis of work. Published during the same year as the peaceful occupation of Czechoslovakia and the annexation of Austria by the Germans, and just a year before the outbreak of a world war and the imminent invasion and occupation of Holland and most of Europe, Huizinga even includes warfare as a type of play, perhaps infusing the book with a subtle political statement not about the history of play, but the seemingly malicious joy taken by the Nazi regime in aggressive conquest and annexation.

Huizinga was one of the greatest scholars of his generation and his theories about play remained essentially unchallenged for several decades. In the late 1950s Roger Caillois (1958; trans. 2001) criticized Huizingas omissions, such as descriptions and classifications of games, and took issue with his definition of play. In Caillois opinion Huizinga overemphasizes the notion of the secret or mysterious element of play, when in fact, as Caillois correctly points out, play is almost always spectacular or ostentatious and tends to remove the very nature of the mysterious (Caillois 2001: 4). Caillois sets the precedent among scholarly monographs on sports of enumerating a list of formal characteristics that define the nature of play. For him, play is: free; separate; uncertain; unproductive; regulated, or governed by rules; and fictive, or make-believe (Caillois 2001: 910, 43). His focus is primarily on sociological constructs of modern rather than medieval sports.

Like Caillois before him, Allen Guttmann (2004: 16; 1st ed. 1978) also takes issue with some of Huizingas ideas in his introductory remarks in a book about modern sports, but he, too, uses an inductive method and defines sports according to his own list of modern criteria and standards, as follows: secularism; equality of opportunity to compete and in the conditions of competition; specialization of roles; rationalization; bureaucratic organization; quantification; and the quest for records. This list of essential ingredients excludes medieval activities and practices because they do not fit neatly into his theoretical framework. Insofar as sportsmen and sports records are concerned, Guttmann (2004: 512) also coins the term marvelous abstraction, as follows: What is a record in our modern sense? It is the marvelous abstraction that permits competition not only among those gathered together on the field of sport but also among them and others distant in time and space. The concept of the marvelous abstraction refers to deeds not only preserved for posterity in a written record, but also reproduced without interruption to the present day. This concept, Guttmann argues, informs and defines modern sports, and is neither apparent nor evident in the Middle Ages. His depressing conclusion with regard to medieval sports is that: The Middle Ages had their acrobats and tumblers and jongleurs, but they were not a period of athletic specialization (Guttmann 2004: 38). His opinions on the matter are shared by Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning (1986) and Georges Vigarello (2000). Guttmanns comment, however, once again inadvertently points to the very difficulties faced by a single author when analyzing medieval European sports, as it is impossible for one scholar alone to master all of the languages of medieval Europe, let alone pursue such extensive archival and archaeological study as to unearth the entire sporting past of the continent. In consequence much of the single-authored scholarship on the subject, while undoubtedly valuable, also tends necessarily to be uneven in chronological, geographic, and material coverage.

Next page