William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

Macken House, 39/40 Mayor Street Upper

Dublin 1, D01 C9W8, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2023

Copyright Christopher Hadley 2023

Cover illustration Joe McLaren

Christopher Hadley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008356699

Ebook Edition January 2023 ISBN: 9780008356705

Version: 2022-12-10

For Rebecca

Alder was a mender. He could rejoin. He could make whole. A broken tool, a knife blade or an axle snapped, a pottery bowl shattered: he could bring the fragments back together without joint or seam or weakness It was a joy to me Working out the spells and finding sometimes how to use one of the True Words in the work to put back together a barrel thats dried, the staves all fallen in from the hoops thats a real pleasure, seeing it build up again, and swell out in the right curve, and stand there on its bottom ready for the wine.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Other Wind

There has never been a better time for lovers of Roman roads those seeking, and seeking to understand, the indelible but elusive lines tattooed onto the face of Britain by the Roman occupiers long ago. Thanks to new technologies and the recent labours of archaeologists and the Roman Roads Research Association, we can track and map thousands of miles of road more accurately than ever before and explain the extraordinary role that they played in the military, social and economic life of Roman Britain, as well as during the centuries that followed. As I write, our understanding of the roads is changing constantly, with the map being redrawn weekly, not only because previously lost roads are being rediscovered, but also because we are learning that even those well known and long known didnt go where we thought they did. Such knowledge changes our ideas about trade and industry and communications, about where forts were built, and about why and how the Roman invasion and occupation progressed. It changes the maps we have in our minds when we think about the past.

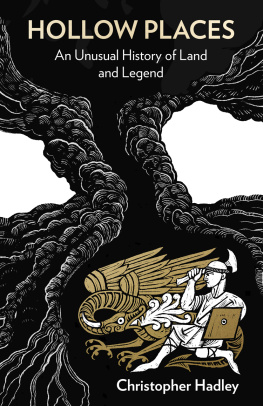

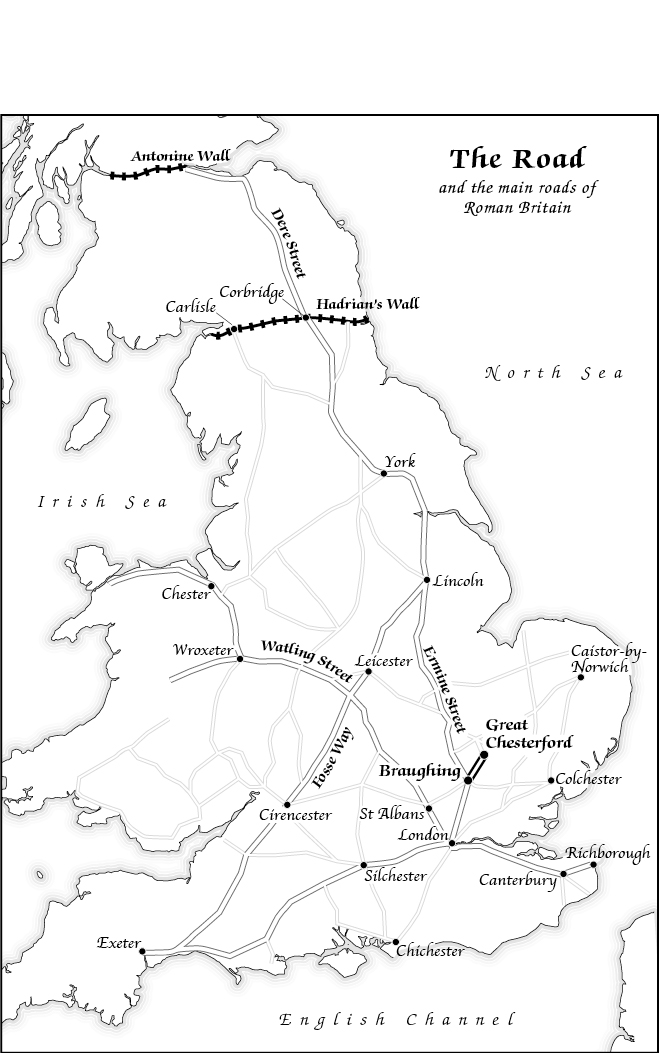

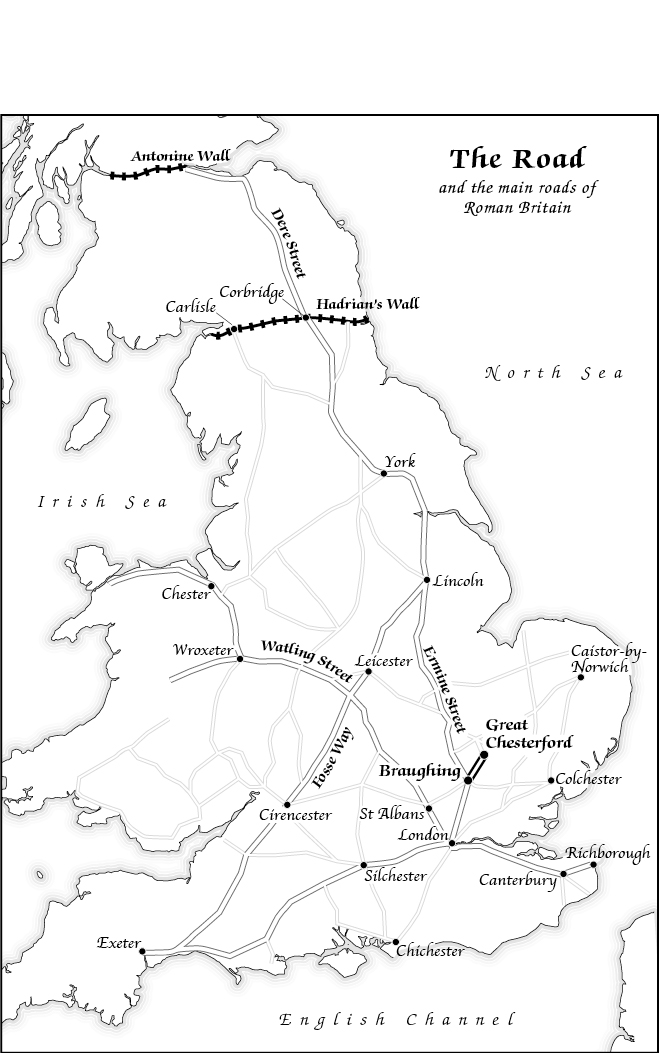

Roman road hunting is a well-established if not always venerable tradition in the historiography of Roman Britain. Confirming a route is called proving the line. It is the province of antiquaries, poets and local enthusiasts, as well as academic historians and archaeologists. I am interested in all these perspectives. This book, like my last, Hollow Places, is about a personal hunt across time. I go in search of one road in particular and in doing so hope to tell the wider story of Britains Roman roads. I could have trekked one of the great ways or iconic roads Ermine Street, say, between Lincoln and the Humber, the Ackling Dyke from Old Sarum to Badbury Rings, or the Stanegate in the shadow of Hadrians Wall instead I follow one of the lesser ways. Not an insignificant way. Oliver Rackham, the great historian of the English countryside, wrote about those Roman roads that survive only in bits and pieces between places that stopped being important long ago, calling them more eloquent than any that became modern roads. He singled out one in particular. But what of the road between Braughing and Great Chesterford? he wrote. There were still people in these Essex-Hertfordshire backwoods for whom bits of it were of use as local roads. Every few years, through the darkest of the Dark Ages, there has been somebody to take a billhook to the blackthorn on two short stretches of Roman road, which stand out by their straightness amid the maze of lanes.

This is the road we shall follow. An eloquent road, so it will speak to us if we are prepared to listen. Eloquent suggests fluent, forcible, powerfully expressive, lyrical. It can be all these things. Lets have a conversation with this road. It will tell us stories.

While this book celebrates the new precision, the latest findings and the determination to set Roman road research on sound academic footings, I am determined not to turn my back on the amateurs, the romantics and even the dilettantes, nor to shun those qualities of a Roman road that give them their greatest allure. We mustnt reduce these magical relics to three-letter acronyms, to GIS and to CAM, or to GPS. Here youll find that the imagination is just as essential a tool for getting at the roads as are aerial photography and LiDAR. The hunt for a roads essence and why it fascinates us is as important as the hunt for its physical remains, which is why I widen the customary evidence base for a road to poems, church walls and hag stones; oxlips, killing places and Rebecca West; hauntings and immortals and things buried too deep for archaeology. After two thousand years, the road I am hunting is now made of these things as much as it is of gravel and sand. It is important to remember at the outset that many of us who love Roman roads love them not because they are roads, but for what they have become over centuries of use and misuse.

There have already been many excellent histories and technical treatises on the roads the Romans built during their occupation of Britain. I havent set out to write another, although you will find some road history and a bit of technical stuff here. Nor is this book a general history of the Roman province of Britannia, but inevitably there are quite a few stories from those times in these pages. They are irresistible.

This book is not one of those poetic encounters with nature: a walk to exalt in the countryside and the act of walking, while exorcising demons or mulling over some personal tragedy, and yet it bears a passing resemblance to such writing from time to time.

It is a hunt through time and space for a physical road but mostly for its quiddity and for its charms too though even that often seems like a proxy for searching for something else. I think that something else might be the power to time travel. I have discovered various ways to accomplish that. I began by pretending to walk in the footsteps of the legions but I want to get beyond that clich; to get at what it is to encounter something concealed in the landscape that transports us into the past, or transports the past to us in the present. A Roman road is uncanny, singular in its capacity to reflect both continuity and change over such a long period of time; it can manipulate time and space and open up no end of ways to the past: historical, archaeological, anthropological, technological and poetic. It makes a fine time machine.

Many accounts of walking in someones footsteps are about the famous writers or artists, soldiers, explorers, the great and the (not always) good. Their journey is reconstructed from written accounts, histories and letters and diaries and such like. There is nothing so grand or definitive here to guide my steps, only the merest trace of the road written in the landscape in a strange alphabet that can be read only with a remarkable array of tools and strategies. Many of them are technical, some are literary and artistic, but chief among them is a restless curiosity and a romanticism. A Roman road is surprisingly good at feeding that.