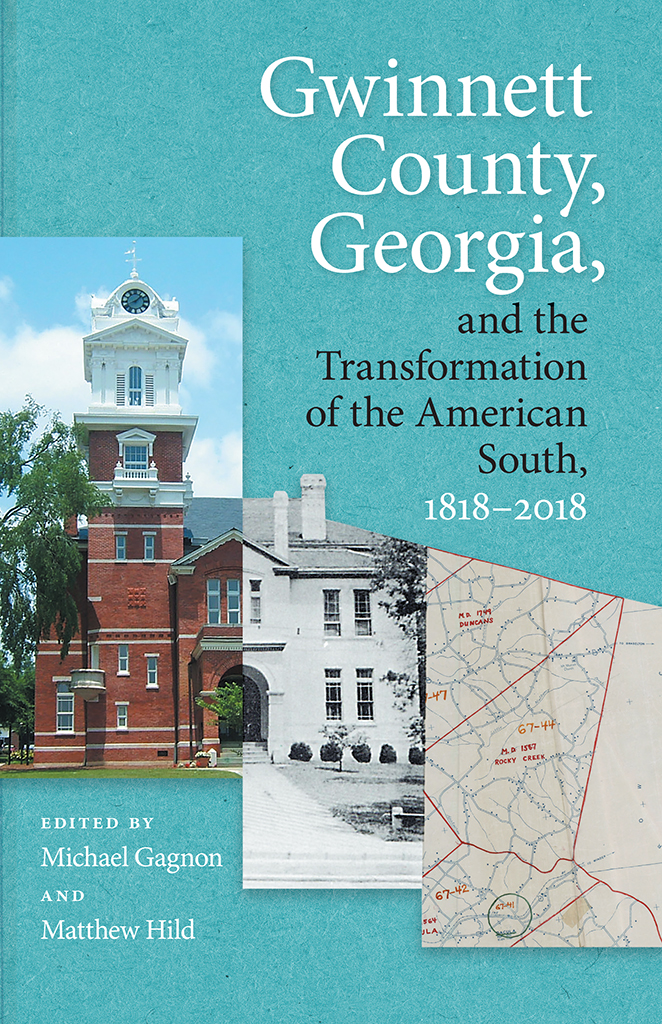

Gwinnett County, Georgia, and the Transformation of the American South, 18182018

Gwinnett County, Georgia, and the Transformation of the American South, 18182018

MICHAEL GAGNON & MATTHEW HILD, EDITORS

THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS

ATHENS

2022 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Set in 10.25/13 by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed digitally

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021922994

ISBN: 9780820362106 (hardback)

ISBN: 9780820362090 (paperback)

ISBN: 9780820362083 (ebook)

CONTENTS

| BRADLEY R. RICE |

| RICHARD A. COOK JR. |

| LISA L. CRUTCHFIELD |

| MICHAEL GAGNON |

| KEITH S. HBERT |

| MICHAEL GAGNON AND MATTHEW HILD |

| R. SCOTT HUFFARD JR. |

| DAVID B. PARKER |

| MATTHEW HILD |

| DAVID L. MASON |

| WILLIAM D. BRYAN |

| CAREY OLMSTEAD SHELLMAN |

| ERICA METCALFE |

| KATHERYN L. NIKOLICH |

| EDWARD HATFIELD |

| MARKO MAUNULA |

| JULIA BROCK |

Gwinnett County, Georgia, and the Transformation of the American South, 18182018

BRADLEY R. RICE

In 1818 Georgia created three new counties and named them for the states signers of the Declaration of Independence: George Walton, Lyman Hall, and Button Gwinnett, the signer who died in a 1777 duel with Lachlan McIntosh, the Revolutionary War general who acquired his county namesake twenty-five years sooner than his victim. Walton and Hall Counties lie to the south and north of Gwinnett, respectively. The Chattahoochee River forms almost the entirety of the northwest border of Gwinnett County. On the opposite side of the river the Cherokee Nation struggled to maintain its autonomy for another seventeen years before it faced final removal to Indian Territory.

Gwinnett County lies in Georgias upper Piedmont region astride the Eastern Continental Divide. The northwestern edge of the county along the Chattahoochee drains to the Gulf of Mexico, but the majority of the county falls into the Ocmulgee-Oconee-Altamaha basin, which drains to the main body of the Atlantic Ocean midway along the Georgia coast. The headwaters of the Yellow, Alcovy, and Apalachee Rivers rise near Lawrenceville, but they are little more than creeks until they flow farther south. As a consequence Gwinnett County lacks the sort of rich soil and well-watered bottomland that characterizes the lower Piedmont. For a long while, no significant towns or cities grew up in the county, and it remained a lightly populated farming region from its founding until the late twentieth century, when Atlanta pulled the county into its orbit. Today Gwinnett County approaches a million residents, and its story deserves serious historical attention.

The history of Gwinnett County differs significantly from that of the other counties that hosted the first wave of Atlanta suburbanization. Thanks to direct railroad connection, DeKalb County and its seat of Decatur fell into the Atlanta orbit from the mid-1840s onward. Likewise, Cobb County (Marietta) and Clayton County (Jonesboro) stood astride 1840s rail lines linked to the Atlanta hub. On the other hand, railroads did not reach Gwinnett until 1871, six years after the Civil War. Even then, the first line in the county bypassed the tiny county seat village of Lawrenceville. Unlike many of Georgias counties, Gwinnett lacked a central identity revolving around a dominant county seat town where almost all the economic and political elite resided and interacted. Several small towns in Gwinnett, especially those along the countys two late nineteenth-century railroad lines, served their immediate trading areas but not much more.

World War I brought a large federal installation and surrounding growth to DeKalb County. After the Great War, the Dixie Highway came through Cobb County with great fanfare on its way to Atlanta. Branches of the Dixie Highway extended onward from Atlanta through DeKalb and Clayton Counties on their way toward Florida. Meanwhile, highway maps showed no major routes in Gwinnett for early automobile travelers and cross-country truckers. The county did not even boast its first paved road until 1924. Financial woes brought on by the Great Depression of the 1930s prompted Milton County to the north and Campbell County to the south to merge with Atlantas home county of Fulton. Soon after that World War II brought rapid expansion of military facilities in and near Atlanta. The close-in suburbs benefited with the location of a huge bomber plant in Cobb County, the expansion of the airport facility in DeKalb, and the creation of a sprawling quartermaster depot along the railroad in Clayton. But there was nothing for Gwinnett. By 1950 the county was home to only 32,320 peopleonly two thousand more than in 1920. Thus, Gwinnett continued essentially to be an agricultural county without a cohesive identity well into the second half of the twentieth century.

Finally, in the late 1950s the freeway penetrated Gwinnett County via I-85, but when the construction of I-285 around Atlanta began in the 1960s, Gwinnett remained out of the loopfiguratively and literally. Gwinnett County came late to Atlantas suburbanization party, but its time would come. Some moderate suburban-type growth occurred in Gwinnett in the 1950s and 1960s as residential subdivisions crept across the line from adjacent DeKalb County and development inched up I-85. The U.S. Census Bureau incorporated Gwinnett into the Atlanta metropolitan area for statistical purposes in time for the 1960 count. Still, as late as the end of that decade only 69,000 people lived in the 433-square-mile county northeast of Atlanta. The explosion finally came. Growth from 1969 to 2018 amounted to a staggering 1,243 percent. The county exceeded the half million mark by the 2000 census and will soon reach a million. Gwinnett is now Georgias second most populous countyclose behind Fulton, which contains most of the city of Atlanta. Not Fulton but Gwinnett is Georgias most ethnically diverse county. Among the near million residents there is no majority ethnic group, and that is a new phenomenon for the state.

If suburbanization came late to Gwinnett, serious historical attention has come even later. Scholars, including myself, have long advocated for increased historical attention to suburbanization. Kenneth Jacksons 1987 Crabgrass Frontier is the seminal work in the field, but much remains to be doneespecially for metropolitan Atlanta. Over the eighteen years that I edited the Atlanta Historical Societys quarterly Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South (19822000), we never published an article about Gwinnett County. We carried scholarly work about Macon and Augusta, and several articles that dealt with the state or region as a whole. We published articles set in Clayton, Henry, DeKalb, Cobb, and, of course, Fulton Counties, but I dont recall having any Gwinnett manuscripts submitted. Gwinnett County garnered only slight mention in my own 1983 account of Atlantas role in the rise of the Sunbelt. Kevin Kruse gave passing attention to Gwinnett in his 2005 study White Flight, which discussed how the departure of white people from Atlanta shaped political conservatism. His account drew mainly from the graduate school work of Edward Hatfield, one of this volumes contributors. Urban historian Michael Ebner briefly profiled the county in comparison with other suburbs across the nation in an article in the