This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1998 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

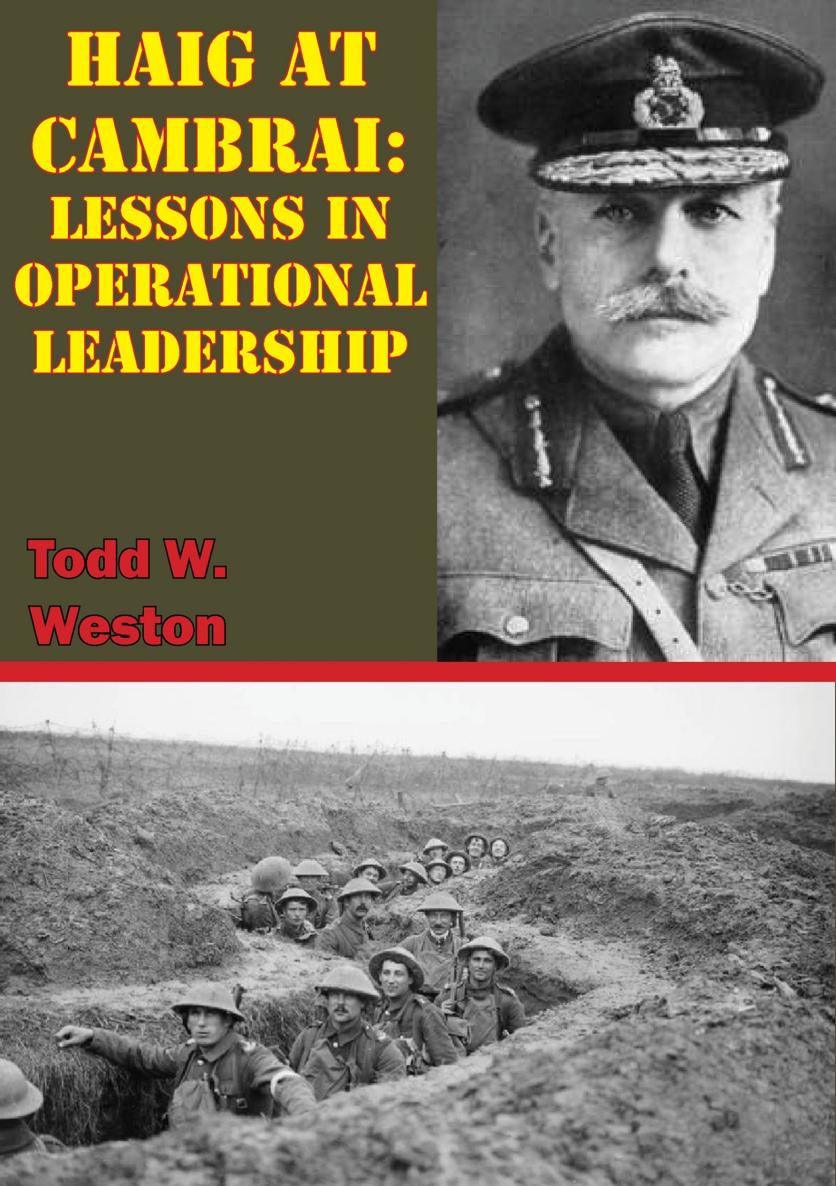

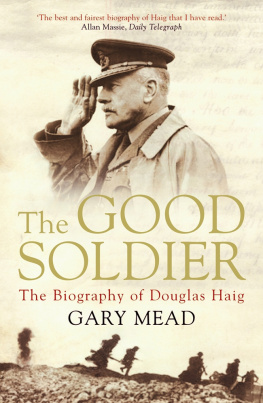

Haig at Cambrai: Lessons in Operational Leadership

By

Mr. Todd W. Weston Department of State

Haig at Cambrai: Lessons in Operational Leadership

The Battle of Cambrai can, in terms of warfare, be seen as the bridge between the 19 th and 20th Centuries. For the first time, new technologies in the form of tanks, aircraft and artillery came together in a single operation and in a form which would influence their use for the remainder of the century. Blitzkrieg, combined arms and AirLand Battle can all trace their modem roots directly to this brief operation overseen by the British Commander in Chief (CINC) on the Western Front, Sir Douglas Haig and conducted by the British Third Army in November 1917. As the American military prepares to face the challenges of warfare in the next century, it seems appropriate to return to this relatively obscure, though watershed, operation in search of lessons which may prove useful for future operational commanders.

A new epoch in artillery tactics had dawned, and the crux of the art of war-surprise -had come into its own despite the assembly of nearly 500 tanks. The battle seemed lifted out of the context of the Western Front; its time pressures, thrusts and parries, its fluidity, its chances and disappointments, were comparable with some of the great battles of the Second World War; and the seeds of Hitler's Gotterdammerung were sown here. {1}

The dynamic nature of the operation, combined with the use of new technology and tactics heralded the return to maneuver warfare and a chance for the rebirth of operational art. Unfortunately, Douglas Haig was unable to convert surprise, a successful penetration maneuver and a technological edge into a decisive victory. Why that happened is precisely the question that must be asked in order to understand the lessons Cambrai holds for todays operational leaders. In simplest terms, Haig's lack of success at Cambria can be traced directly to his inability to define and communicate his operational intentionsthereby pointing out a timeless truth for the operational commanderthat a CINC's first responsibility is to accurately define and clearly communicate his intent for any given operation.

Also contributing to the reversals at Cambria was Haig's penchant for involving himself in tactical decisions and thereby neglecting his proper role as the link between the strategic and operational levels of war. In this sense, Haig failed to understand the optimal balance between centralized and decentralized command and control which is so crucial to todays operational level commanders {2}

Although operating under the constraints of economy of force, much as will future U.S. CINCs, Haigs actions at Cambrai added a final characteristic that has relevance to the modern commander. A CINC must, then as now, understand the overall context of his activities and be willing to resist pressure (especially self-imposed as in Haig's case) to commit forces for anything other than the most compelling reason. At Cambrai, even though he was aware that he did not have sufficient forces to exploit success, Haig chose to proceed with an operation largely to salvage positive results from a disastrous year, relieve pressure on another front, and possibly in an effort to save his own job. After the unprecedented gains of the first day at Cambrai, the church bells rang in England for the first time since 1914. Two weeks later, after a successful German counter-attack the British Government was demanding a board of inquiry into Haig's conduct at Cambrai.

While the U.S. military places great emphasis on ensuring a commander's intent is accurately conveyed to subordinate commanders, events as recent as Vietnam and the 1991 Gulf the art communications, may not find root in his subordinate commanders. In The General's War , War aptly demonstrate that a CINC's vision, even after extensive coordination and with state of the authors make note of the fact that to this day Schwartzkopf blames Franks for being too slow and letting too many Iraqis escape before the cease-fire. {3}

Haig as a Commander :

Since the end of the First World War, Sir Douglas Haig, perhaps more than any other commander in the conflict, has become a symbol of the senseless carnage of the Western Front. From his arrival in France in 1914 as a corps commander for the British Expeditionary Force until the Armistice of 1918, Haig has served as a symbol to many of all that was wrong with both the British military and armed forces in general. He was ultimately portrayed by many in Britain as the executioner of the lost generation or, at best, as an insensitive leader who was far too casual with the lives of the soldiers entrusted to him.

Today, Haig is remembered only for his campaign on the Western Front, which looks, from a contemporary perspective, as a monument to tragic ineptness. It was Haig after all, in his first major operation as the British Commander in Chief on the Western Front, who opted to continue the Somme offensive for three months after suffering 60,000 casualties on the first day of the operation. He followed this in early 1917 with a two-month battle at Arras where he accepted an average of some 4,000 casualties a day to follow up on a minimal gain. {4}

The next offensive was a similar story. Originally known as Third Ypres, it developed into a battle at Passchendaele during three horrific months of attrition warfare. What his detractors have forgotten, however, is that Haig's position was not nearly as simple as one would believe. At both the Somme and Arras, Haig was essentially forced to act, at locations not of his own choosing, based on the need to relieve pressure on the French Army which had been bled white by German pressure at Verdun and was on the verge of mutiny. Later, Ypres and Cambrai can be seen, in fact, as being part of Haigs belief that the French would no longer aggressively pursue the war. These and later operations were also an attempt to realize Haig's vision that, ''his Army would be the weapon for the achievement of victory in 1918 and that its methods must be adapted to changed conditions. {5}