Introduction

Run Dont walk from the Blob!

It crawls! It creeps! It eats you alive!

Trailer for The Blob, 1958

On a clear spring day, I make my way to the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. Its located in a part of the university campus which has a whiff of Hogwarts about it, with a maze of courtyards, the entrance hiding somewhere within. The Hunterian is the oldest public museum in Scotland, more cabinet of curiosities than modern scientific institution. Roman artefacts, feathered Maori cloaks and fossils sit side by side in this museum, which reminds me of a church with its pointy gable and simple rosette glass window, the high ceiling worked in the same dark wood as the carved balustrades. But its neither the neo-Gothic charm nor the wonderful collections that brought me to the Hunterian. I am here to see a glass bottle, about as big as a hand, fitted with a fat stopper and two gilded labels, handwritten. Im here to see an old phial filled with slime.

Some forms of matter seem to unite the properties of solids and liquids. For example, cats: which category do they fall into? The answer should be an easy one, physically speaking: solids retain their shape, while liquids fill their container. Cats seem unequivocally to be solids, until they demonstrate their aptitude for easily slipping into the smallest of gaps, almost flowing into them. The French physicist Marc-Antoine Fardin researched, tongue-in-cheek, the physical classification of cats between solid and liquid, touching on his specialist area of rheology, the study of the flow of matter. In 2017 he was awarded the Ig Nobel Prize, a not altogether serious award for suitably original research.

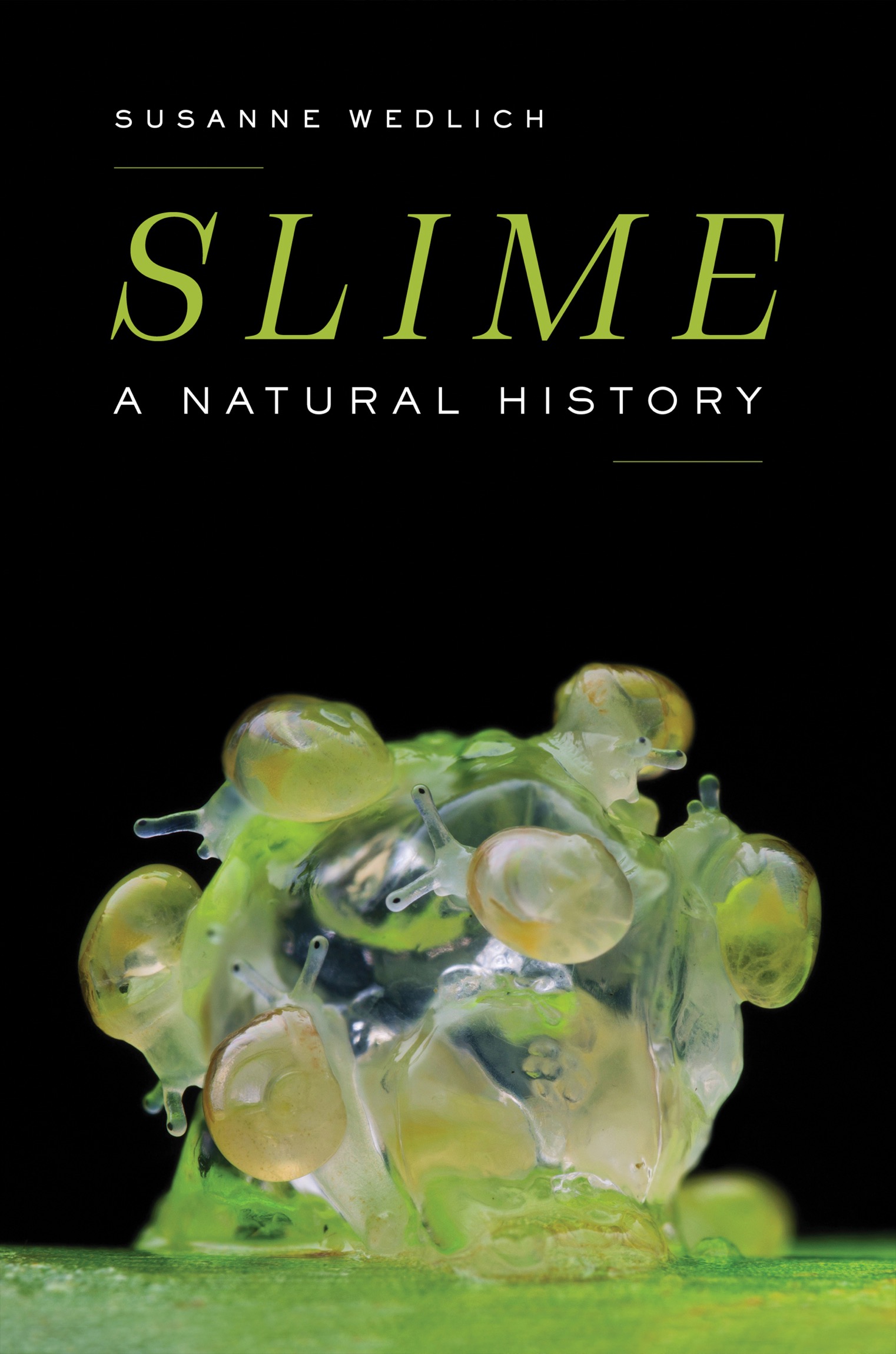

Matter which exists somewhere between solid and liquid is not restricted to cats, though, and slime is its most important embodiment in nature. It is protean in its behaviour; it is the material of interfaces and has a unique place in our imaginations. We are all creatures of slime, but some of us are more creative than others: there is a menagerie of oozing organisms to be found in all the worlds habitats, frequently changing these environments to suit their needs by leaving their glistening marks. It may also be a surprise to discover that microbes were not only the dominant, but also the only form of life on Earth for billions of years, with slime, as the minence gluante, propping up their power and setting in motion processes across the globe which still shape it today.

The long reign of slime concerns the supposedly boring stages of evolution which preceded the emergence of the first animals. Popular portrayals often neglect this seemingly endless span of time, but slime was paving the way for life on Earth then, particularly for higher organisms like us. It may even have facilitated our very existence. It is a legacy we humans prefer to ignore. Here, we benefit from slimes hidden nature, with its visible manifestations banished inside our bodies. Better not to think about slime, which seems to carry the scent of our baser instincts, of sex and weakness, of sickness and death. We regard it as an object of universal disgust, only admitting it at least in industrialized societies into our hyper-hygienic worlds in controlled doses, as an entertaining expression of the depths of the human psyche.

Modern monsters can rarely do without slime and slobber, be it on screen in movies like Alien or in stories like the ones H.P. Lovecraft wrote. In a sense, slime makes humans biological creatures, yet becomes the line of demarcation between us and the Other. Is this because slime as a phenomenon is slippery to grasp but nonetheless elicits strong emotions? Physically speaking, it can be defined and therefore contained. Slime is an extremely aqueous and viscously fluid hydrogel, which also bears the properties of a solid under certain conditions. Biological slimes are so flexible that they can easily adapt as required. Scientists are trying to copy or emulate these sophisticated structures for applications like soft robots, smart wound dressings or tailor-made glues, but often come unstuck when attempting to unravel their biological complexity.

Yet the first steps have been taken and, in the future, it may be possible to imitate even more specialized slimes, which serve as the adhesives, lubricants and selective barriers vital to microbes, animals and plants. There is probably no single living creature that does not depend on slime in some way. Most organisms use slime for a number of functions, be it as a structural material, as jellyfish do; for propagation, as plants do; to catch prey, as frogs do; for defence, like the hagfish; or for movement, like snails. The ubiquity of slime is little recognized, because many biological hydrogels hide behind pseudonyms like mucilage, mesoglea, marine snow and, of course, mucus, which barely give an inkling of their true and common nature.

Since many of these biological hydrogels are secreted outwards, they work beyond the single organism. Even in the natural environment they are invisible cement, holding different ecosystems together, from desert to coastline to marine habitats, primarily at the interfaces where water, land and air meet. Slime is a central cog in the world we live in and even slight changes could have global effects. The looming reality of climate change and other environmental crises like the loss of ecosystems and biodiversity threatens hydrogel-based relationships and processes. However, a new equilibrium in a warmer world might also favour slime in some habitats, allowing it to return to dominance. It would be a step back into an early era of evolution, a new era of slime.

The importance of slime is similarly far-reaching inside the human organism, equipped as it is with four different gel-like systems to fortify it with living walls, gates, armour and moats. Most pathogens founder at these defences, while welcome microbes find refuge as tenants and mercenaries. Like materials science and climate research, biomedicine has been waking up to its own slime blindness; defective hydrogel barriers have an important part to play in infections, chronic intestinal inflammations, cystic fibrosis, cancer, heart attacks and a series of other ailments.

Without slime we would be overrun by pathogens: hydrogels are sticky traps for microbial invaders which actually produce slime as well. Keeping our distance from unknown hydrogels is expedient and our aversion to all things slimy well-founded, as the science of disgust shows. But does even the word slime have to elicit gagging histrionics? Our all-too-often highly emotional response to viscous materials can lead to ignorance as we forget that slime is the very foundation of our biology, an essential for our health and our environment. And that kind of ignorance is a very modern idea.