First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

West Midlands Publications

an imprint of

University of Hertfordshire Press

College Lane

Hatfield

Hertfordshire

AL10 9AB

Mary Nejedly 2021

The right of Mary Nejedly to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-912260-43-0

Design by Arthouse Publishing Solutions

Printed in Great Britain by Charlesworth Press, Wakefield

Contents

List of illustrations

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

1 Introduction

2 Parish apprentices and the old Poor Law

3 Birmingham workhouse children

4 The industrious child worker

5 Child labour and the family economy

6 Education, industrialisation and child labour

7 The health and ill-health of child workers

8 Set adrift: Birminghams child migrants

9 Childhood redefined

10 Conclusion

Appendix

Bibliography

Illustrations

Tables

2.1 Comparison of destinations three Warwickshire parishes, 17501835

2.2 Comparison of destinations three Worcestershire parishes, 17501835

2.3 Comparison of destinations three Staffordshire parishes, 17501835

3.1 Children resident in the Birmingham Asylum for the Infant Poor, 184547

3.2 Children in the Birmingham Asylum for the Infant Poor, 1851

5.1 Average weekly wages in Birmingham, 1842

5.2 Comparison of average national weekly wages with average wages in Birmingham, 184145

5.3 Average weekly wages in Birmingham metal trades, 1866

6.1 National Society and British Society Schools in Birmingham

6.2 Occupations employing the largest number of children and average age of starting work, Birmingham Educational Association Survey, 1857

7.1 Industrial injuries at Birmingham General Hospital, AprilJune 1862

8.1 Reasons for admittance to the Birmingham Emigration Homes, 187879

Figures

5.1 Weekly wages at R. Heaton & Sons, 1 March 1861

Abbreviations

BAH | Birmingham Archives and Heritage |

BPP | British Parliamentary Papers |

SCRO | Staffordshire County Record Office |

TNA | The National Archives |

VCH | Victoria County History |

WALS | Wolverhampton Archives and Local Studies |

WCRO | Warwickshire County Record Office |

WoCRO | Worcestershire County Record Office |

Acknowledgements

My greatest debt is to Dr Malcolm Dick of the University of Birmingham, for his expertise, support, guidance and encouragement. His insightful comments and enthusiasm for this subject have continued to inspire me. My thanks are also due to Professor Carl Chinn and Professor Jonathan Reinarz for their advice and helpful suggestions.

I would also like to thank the staff of the Record Offices of Staffordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire, together with staff at The National Archives, Wolverhampton Archives and Local Studies, and the British Library for their help and assistance with my research. The majority of my research for this study was undertaken at the Wolfson Centre for Archival Research at the Library of Birmingham, and I am particularly grateful to the archives staff for their valuable contributions.

I am grateful to the editor of Family and Community History for publishing an article based on aspects of the research in this book, and to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family for their ongoing support and keen interest in my book, especially Steve, Rob and Kate.

Introduction

My first job came when I was only a little over six years of age; it was turning a wheel for a rope and twine spinner at Robs Rope Walk, Duddeston Mill Road, Vauxhall, Birmingham. I received 2s 6d per week, and worked from six in the morning until six at night.1

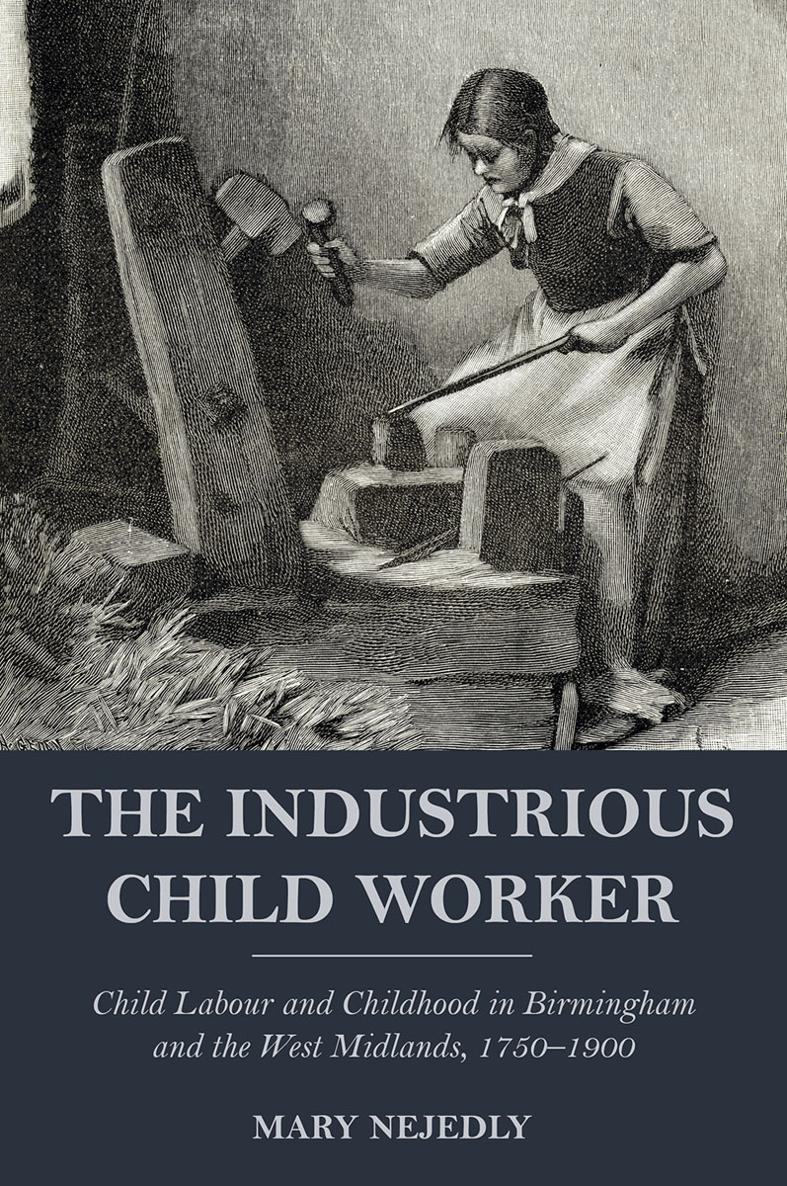

Will Thorne was very young when he began work in 1863, joining thousands of young child workers in Birminghams factories and workshops. If he had arrived at the gates of a cotton mill in search of work, six-year-old Thorne would have been refused employment because he was too young, but legal restrictions on child labour in 1863 did not apply to all sectors of the economy. Government legislation aimed at regulating and restricting the employment of children was first introduced with the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802, followed by a series of Factory Acts during the nineteenth century. However, it was only in 1867 that employment of children below the age of eight was prohibited in all factories and workshops, despite the large numbers of children who worked in manufacturing industries other than textiles.2 Studies of child labour have examined the experiences of child workers in agriculture, mining and textile mills, yet surprisingly little research has been concentrated on child labour in industrial towns that had quite different patterns of economic activity and organisation.3 This book explores child labour in Birmingham and the West Midlands from the mid-eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century, focusing on the economic contributions of child workers under the age of 14 and their experiences of a childhood dominated by work. It offers insights into the relationship between child workers and their families, highlighting the extent to which childrens education and health could be damaged for the economic benefit of families as well as employers. Furthermore, it enhances our current knowledge of childhood and child labour by illuminating this previously unexamined aspect of the Birmingham and West Midlands economy, arguing that child labour was not a short-lived stage of the early Industrial Revolution but an integral part of industry in the region until towards the end of the nineteenth century.

The literature on child labour has expanded over the last three decades to include the significance of child workers contribution to industrialisation and the relative importance of childrens earnings to the family economy.4 More recently, attention has turned towards the themes of child workers health, diversity of employment and agency among child workers.5 These studies have informed the arguments developed in this book, which examines the nature and extent of child labour in Birmingham and the West Midlands and the changes that took place in the levels of child labour between 1750 and 1900; the importance of childrens earnings to the family economy; changes in the intensity of childrens work and the impact of early work on childrens education, health and life chances; and changes in attitudes to child labour and childhood over time, as well as evidence of childrens agency as participants in historical change.