Men and the Emergence of Polite Society, Britain 16601800

First published 2001 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2001, Taylor & Francis.

The right of Philip Carter to be identified as author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-31987-5 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carter, Philip.

Men and the emergence of polite society, Britain 16601800 / Philip Carter.

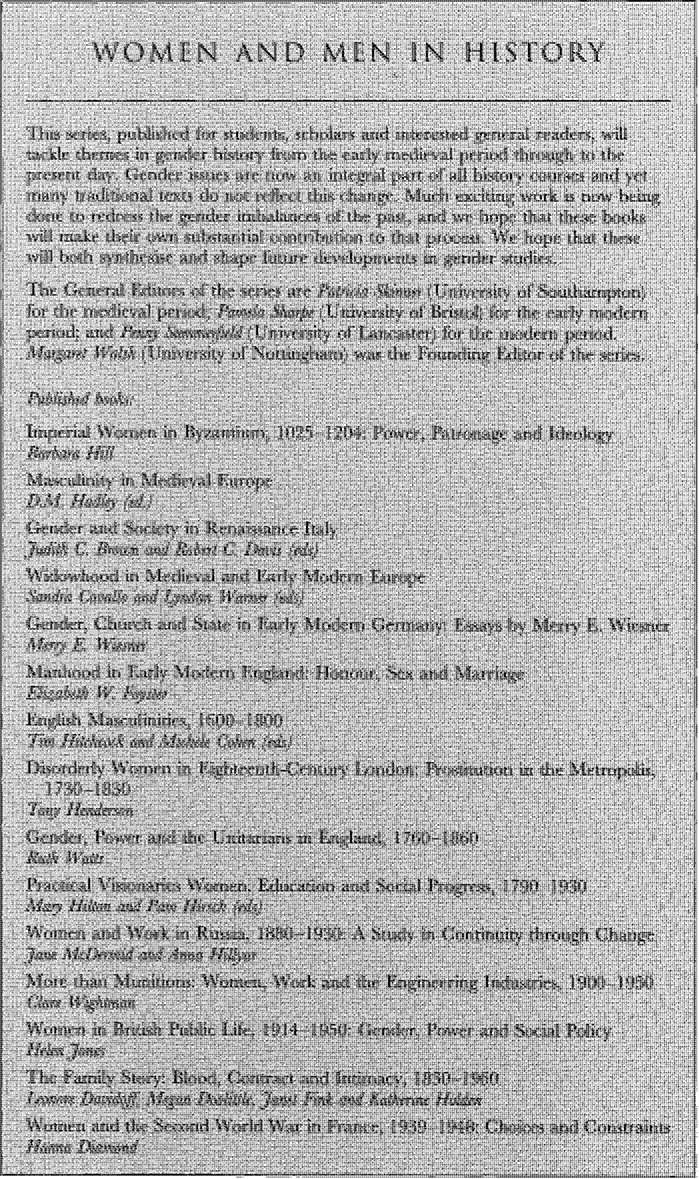

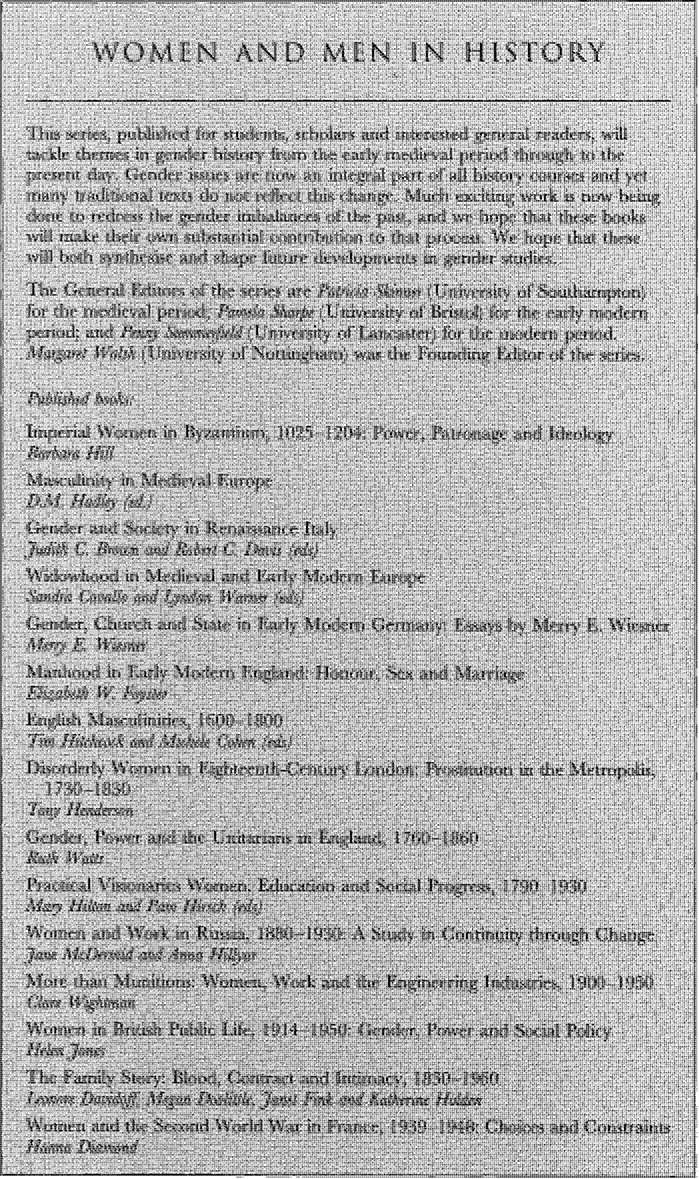

p. cm. (Women and men in history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-582-31986-2 ISBN 0-582-31987-0 (pbk.)

1. MenEuropeHistory. 2. MasculinityEuropeHistory. 3. Courtesy

EuropeHistory. 4. EtiquetteEuropeHistory. 5. EuropeSocial life and

customs. I. Title. II. Series.

HQ1090.7.E85 C37 2000

305.31094dc21

00-041640

Typeset by 35 in 11/13pt Baskerville MT

I have benefited greatly from the comments and support of many people during the writing of this book. My biggest academic debt is to Joanna Innes, who has consistently and generously offered encouragement, guidance and criticism since this projects origin as a D.Phil thesis: it has been a pleasure to study with her over the last decade. I am also grateful to Donna Andrew, Hannah Barker, Laurence Brockliss, Elaine Chalus, Michle Cohen, Elizabeth Foyster, Tim Hitchcock, Martin Ingram, Mary Catherine Moran, Roy Porter, Guy Rowlands, Pamela Sharpe and Alex Shepard for their advice at various stages of research and writing.

Konstantin Dierks, Susan Skedd and David Taylor read earlier drafts of the book and their suggestions have considerably improved what follows. I am especially grateful to Sarah Knott, both for her detailed reading of the manuscript and her stimulating conversation and friendship. I would also like to thank my colleagues at the New DJVB, in particular Michael Bevan, Robert Brown and Annette Peach, for their help and advice. Anne-Pascale Bruneau, Lacy Rumsey and Glenn Timmermans have also been extremely supportive throughout.

Lastly, four people offered reassurance and a sense of perspective when writing made me more blackguard than polite gentleman. This book is for Meg, my brother Tim and my parents Joan and John, with thanks.

We are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce copyright material:

copyright the British Museum; cover: The bow from Franois Nivelon, The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour (1737), by permission of the British Library (British Library Shelfmark 1812.a.28).

Whilst every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material, should we have omitted to locate the copyright holders, we take this opportunity to offer our apologies to any holders whose rights we may have unwittingly infringed.

On 25 October 1773 Samuel Johnson and James Boswell visited Inveraray Castle in Scotland as the guests of the duke and duchess of Argyll. When I went into Dr Johnsons room, wrote Boswell two days later, I observed to him how wonderfully courteous he had been at Inveraray, and said, You were quite a fine gentleman, when with the duchess. He answered, in good humour, Sir I look upon myself as a very polite man: and he was right, in a proper manly sense of the word.

This book examines conceptions of, and the interaction between, Johnsons twin attributes politeness and manliness over the course of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It argues that the period saw the emergence of an explicitly innovative concept of social refinement politeness practised by and within polite society, by which is meant the personnel who sought politeness and the locations, broadly defined as the nation or the city, or as specific venues including coffee-houses, public gardens and the home, where refined conduct was expected and encouraged. My focus here is on the impact of polite society for eighteenth-century definitions of the refined gentleman, and also, given polite societys broad application and appeal, its implication for definitions of manliness, here understood as desirable and emulative male behaviour. To its proponents, the emergence of polite society was a consequence of significant, and welcome, late-seventeenth-century social and economic change, consolidated and further stimulated by the political settlement following the Glorious Revolution (16889). Through these events the nation was, it was argued, becoming more powerful, prosperous, tolerant and civilised. To these writers, politeness was the means to acquire a suitably refined, yet virtuous, personality that proved superior to many existing forms of manly virtue which, on account of their association with elitism, violence or boorishness, were judged detrimental to truly polite sociability.

The precise nature of this improvement in gentlemanly conduct provoked debate among writers advocating a reform of male manners. Of these debates, the most significant was that between polite theorists and mid- to late-eighteenth-century proponents of an alternative discourse of refinement: sensibility. Sponsors of this latter culture claimed that existing forms of polite conduct had lost their moral integrity and had become a source of duplicity and snobbery, not sociability. In its place, sentimental writers encouraged more spontaneous, and hence more genuine, displays of social interaction. This debate over modes of refinement also had consequences for mid- to late-eighteenth-century discussions of gentlemanly conduct, as well as the meaning of manliness in an age now seemingly given over to a degree of emotion traditionally associated with women.