Preface

Do books write themselves? I ask my students every time we begin a discussion of a new monograph. The purpose of this question, now repeated over thirty years of teaching, is to have students explore the personal and professional baggage authors bring to their writing, but the truth of the matter is that every piece of scholarship is a collective, collaborative enterprise. The single author of a monograph is at best a principal investigator who may take both responsibility and credit for the work and certain decisions associated with it, but would never have been in a position to do so without the assistance of many others, including those who have paved the historiographical highway.

The idea for this book was conceived some ten years ago as a much-needed update to the only existing social history of Warsaw during the First World War, Krzysztof Dunin-Wsowiczs Warszawa w czasie pierwszej wojny wiatowej (1974), which contained valuable data but otherwise lacked any kind of comparative perspective, ignored issues of gender and ethnicity, and was based solely on Polish sources. The original plan was for this studys publication to coincide with the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War. Unfortunately, books do not write themselves, and a series of unplanned yet eventful circumstances led to one postponement after another. When I began my research, literature on the social history of the Eastern Front of the First World War was still in its infancy, less than a decade old, though emerging in cutting-edge fashion through the work of Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius on the German-occupied Ober Ost (2000), Peter Gatrell on refugees and the socio-economic history of the war in imperial Russia (1999, 2005), and Eric Lohr on the Russian Empires enemy aliens (2003). The same could be said for a new focus on the social and cultural history of the war in major urban centers, particularly for Berlin by Belinda Davis (2000), Vienna by Maureen Healy (2004), Freiburg by Roger Chickering (2008), perhaps inspiredas I wasby the Capital Cities at War volumes on London, Paris, and Berlin edited by Jay Winter and Jean-Louis Robert (1997, 2007). Since then, Christoph Micks book on the experience of war in Lww (2010), Joshua Sanborns Imperial Apocalypse (2014) on the wartime decolonization of the Russian Empire, Jesse Kauffmans Elusive Alliance (2015) on the German occupation regime headquartered in Warsaw, and Katarzyna Sierakowskas book on Polands Great War in personal documents (2015) have appeared, each with direct bearing on my own, despite differing perspectives and frameworks of analysis. They have recently been joined by Marta Polsakiewiczs published dissertation devoted to the policies of the German occupation regime in Warsaw itself.

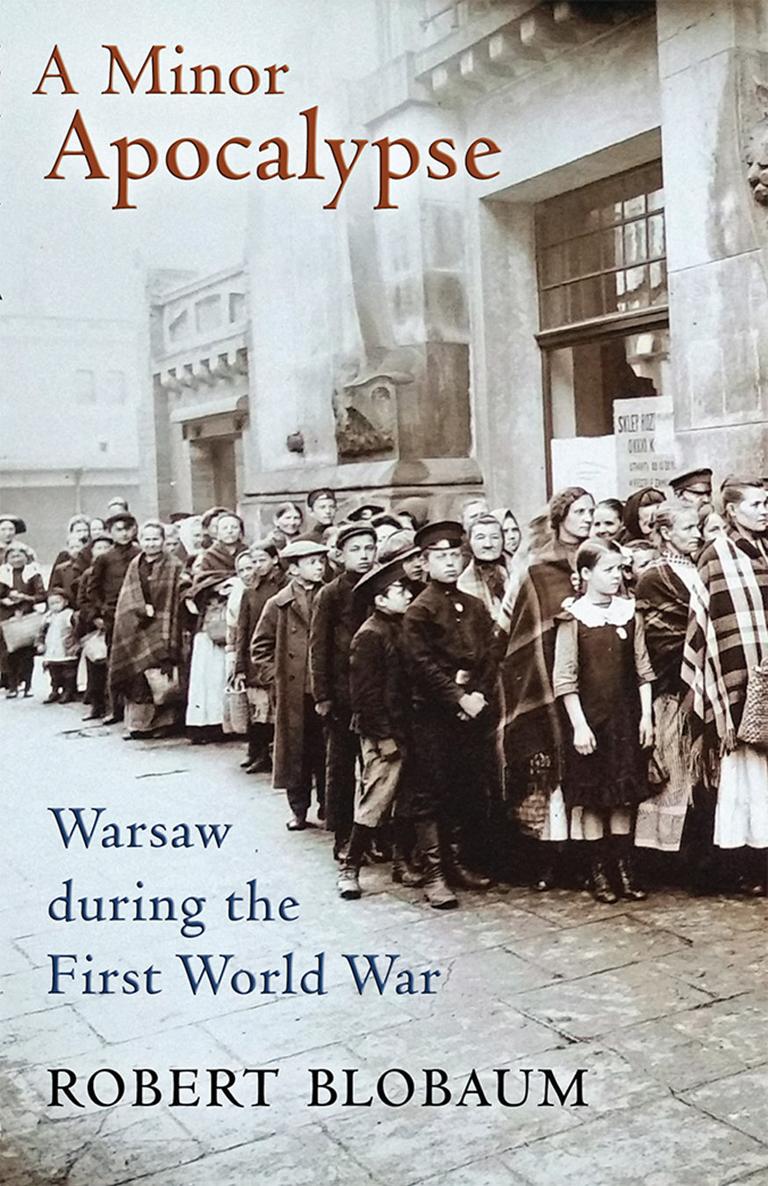

This and other scholarship on the Great War in the east, not to mention the valuable comments of the two anonymous peer reviewers of the prepublication version of this book for Cornell University Press, have compelled me to link my analysis of everyday life in Warsaw to larger issues. As I have argued in these pages and elsewhere, public if not private memory of the lived experience of the Great War in Warsaw was initially obscured and displaced by its end-point, the achievement of Polish independence in 1918, and then buried under the surfeit of memory connected to the terror, violence, genocide, and physical destruction of the city during the Second World War. My goal to recover and interpret this otherwise diminished suffering of Varsovians from 1914 to 1918 led to the adoption of the ironic title of Tadeusz Konwickis 1979 psychological novel about the intended self-immolation of a dissident writer in communist Poland, Maa apokalypsa ( A Minor Apocalypse ), as the most appropriate one for this book.

It soon became clear, however, that in order to justify this study, it was simply not enough to claim that in many respects measures of human suffering in Warsaw during the two wars were broadly comparable. I have had to actually juxtapose the two historical moments according to those areas in which everyday experience was similar, supported by the best available data, and to be clear about where it was not. In turn, comparison of living conditions during the two wars inevitably invited some level of comparison of the two German occupations and my entry into the broader and heated debate about Germanys twentieth-century wars and their relationship to each other. When viewed from the perspective of Warsaw, do Imperial German policies and practices in the occupied east during the first war, as well as interactions with their diverse populations, tell us anything about those of the Nazi occupation regime in the second war? And what about the German relationship to Ostjuden , the religious, Yiddish-speaking, unassimilated majority of Warsaws Jews? Does the road to Auschwitz somehow lead through Warsaw during the Great War in the perceptions and attitudes of the German occupiers toward the metropoles Jewish community?

Even as these concerns became increasingly central, they joined others with which I began my study. Why did so many Varsovians support the Russian cause at the beginning of the war, and what does this say about historians privileging of nationalism in the conventional understanding of Polish history? How politically and socially destabilizing were the mass migrations in and out of Warsaw during the war years? What were the social and political effects of the inequality of suffering brought on by the collapse of living standards? What institutions emerged to attempt to manage the crisis, and why did they fail to do so? How did the impact of the war contribute to the downward spiral of relations between Poles and Jews? What role did the war play in womens acquisition of political rights despite no appreciable feminization of Warsaws labor force? And what can be said about cultural expressions and their sites in wartime Warsaw? Did Warsaw follow European cultural patterns of tacking toward the traditional and the modern simultaneously?

I hope that the attempted answers to these and other questions can begin to fill a yawning historiographical gap, inspire new studies of other cities in central Europe and on the wars Eastern Front, and appeal to both specialist and nonspecialist enthusiasts of the First World War. Some may question the November 1918 end date for this book, since Warsaw remained a city at war beyond the armistice that formally closed the Great War, as the Polish-Soviet conflict came to its northeastern approaches in the summer of 1920, and basic food and other shortages remained prevalent until 1921. Warsaws experience was not unique in this regard; the same could be said of other urban centers in the multiple conflicts of postcolonial Central and Eastern Europe. However, the end of the total war between the European Great Powers and the change in state actors had important effects on the kinds, sources, and levels of assistance to Warsaws stillif slightly lessdistressed Polish and Jewish communities. Regime change in the now internationally recognized Polish capital, the end of the British blockade, and the subsequent arrival of food and other aid from the United States were all important factors in this regard, and if they did not fulfill the promise of significant relief from the ongoing ravages of war, then at least they held out greater hope for human endurance. There were continuities from the years of the Great War, of course, which go forward into and beyond 1919 and which deserve our attention. Nonetheless, the discontinuities, not only political but also social, economic, and cultural, are sufficient in number and substance to require years of additional archival research in new locations and are best left to a future study.