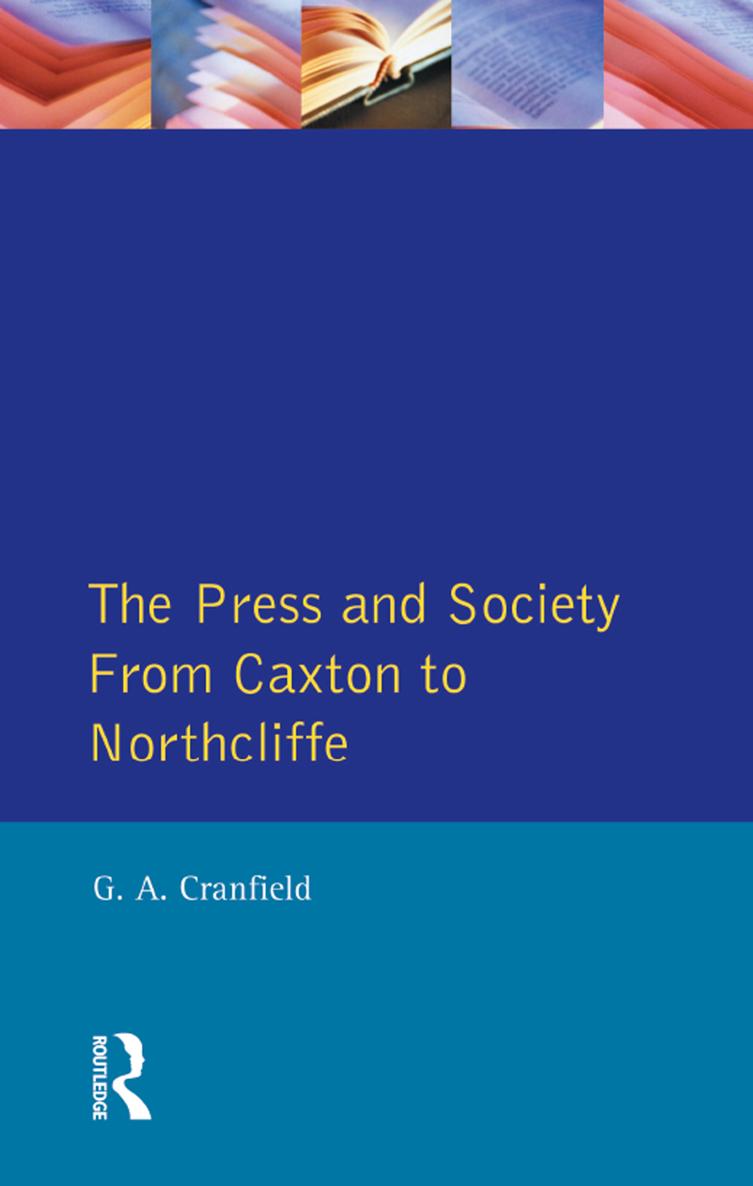

The Press and Society

Themes in British Social History

edited by Dr J. Stevenson

The Englishmans Health: Disease and Nutrition 15001700

Poverty and Society 15001660

Popular Protest and Public Order 17501939

*Religion and Society in Industrial England 17401940

Religion and Society in Tudor England

Sex, Politics and Social Change 18751975

*A Social History of Medicine

Leisure and Society 18301950

The Army and Society 18151914

Social Administration in Industrial Britain 17801850

A History of Education in Britain 15001800

*The Gentry: the Rise and Fall of a Ruling Class

*already published

The Press and Society

From Caxton to Northcliffe

G. A. Cranfield

To my wife

First published 1978 by Longman Group Limited

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1978, Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-48984-4 (pbk)

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Cranfield, Geoffrey Alan.

The press and society.

(Themes in British social history)

Bibliography:

1. PressGreat BritainHistory. 2. JournalismSocial aspectsGreat Britain. 3. Great BritainSocial conditions. I. Title.

PN5124. S6C7 079.41 77-21904

ISBN 0-582-48983-0

ISBN 0-582-48984-9 pbk.

Contents

This book attempts to survey the history of the Press as a whole in relation to the development of society beginning with the introduction of the art of printing into England in 1476. Sheer pressure has meant that the survey ends with the arrival on the scene of Alfred Harmsworth, later Lord Northcliffe and the so-called Northcliffe Revolution is touched on only very briefly. To the authors mind, the history of the Press after this is a subject in its own right. Even so, the author has had to rely heavily upon secondary sources. The problem is particularly acute in the nineteenth century, when to read every issue of The Times would be a Herculean task in itself. When one considers that there were many other newspapers in existence, together with a vast mass of periodicals and magazines, the task becomes impossible. But the problem is by no means confined to the nineteenth century. The author has read as many of the newspapers and periodicals as possible. Of necessity, he has been forced to draw heavily on those writers who have had the great advantage of being able to concentrate on particular newspapers, particular fields, and particular periods. The references (positioned at the end of the text) indicate this heavy dependence. But he has tried to avoid excessive referencing, and apologises in advance to any writer whose work he has pirated without due acknowledgement.

Finally, he would like to express his sincere thanks to Dr Stevenson, the general editor of the series, for his unfailing encouragement and constructive criticism, and to the staff of Longman for their efficiency, helpful comments and patience in dealing with what must have been a dirty script. Their task was not made easier by the fact that the author was 12,000 miles away.

G. A. Cranfield

The University of Newcastle,

New South Wales,

Australia

The introduction of the art of printing did not effect a social or political revolution overnight: few people could read, and the printing press was regarded as a harmless novelty. But as the trade in printed books increased, printers began to show a distinct tendency to stray from the innocuous field of letters into the more exciting fields of religious and political controversy. Such a tendency no authoritarian government could permit particularly one which, like Henry VIIIs, was already grappling with problems of unprecedented size and complexity. In religion, changes were in the air which were eventually to bring about a revolution rather than a mere reformation; in politics, what has, perhaps extravagantly, been called the Tudor revolution in government was under way; and, in the background, there was the slow but sometimes painful adaptation to new social and economic conditions as the feudally organised society disintegrated, to be replaced by a society in which capitalism was to be the increasingly dominant force. The period was, in fact, one of unusual strain and tension, in which the development of the printing press as a critical and possibly subversive force could not be tolerated: and from the time of Henry VIII onwards, Authority sought to control this new threat.

The process was a lengthy one. The problem, like so many of those facing the Tudor monarchy, was entirely new. The first list of prohibited books appeared in 1529, and the following year saw the establishment of the first licensing system. This system was to be operated by ecclesiastics and applied only to books concernynge holy scripture, but it was extended by royal proclamation in 1538 to cover all types of printing, and the clerics were made responsible not only for suppressing theological errors but also for expellinge and avoydinge the occasion of erroneous and seditious opinions. In that age, in fact, religion was politics and politics religion. Gradually the system of control was improved. Mary Tudor brought the Stationers Company into it in 1557, when she granted the Company its charter and gave it wide powers over the craft, and it was completed by Elizabeths great Star Chamber decree of 1586 which set the pattern of regulation for the next hundred years. All books were to be licensed, the Companys powers of search and seizure were confirmed, and the number of master printers, apprentices and printing presses severely limited.

Such was the Tudor system of control. But perhaps too much attention has been paid in the past to its purely negative aspects by historians whose judgement has been clouded by the modern doctrine of the freedom of the Press. Certainly, the Tudors worked on the principle that the peace of the realm demanded the suppression of all dissenting opinion: and in their efforts to stamp out what were called lewd and naughty matters they were remarkably successful. But it has to be remembered that this was a period of uncertainty and insecurity of religious upheavals, economic crises, dynastic doubts, plots and rebellions, of constant fears of foreign invasion. Under such conditions, the government naturally did its utmost to suppress criticism. However, the system was by no means as severe as it may seem on paper and permitted the publication of a surprisingly extensive and varied amount of printed matter, including news.