Stuyvesant Bound

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Copyright 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Merwick, Donna.

Stuyvesant bound : an essay on loss across time / Donna

Merwick.1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4503-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Stuyvesant, Peter, 15921672. 2. New NetherlandHistory. 3. New NetherlandHistoriography. 4. New York (State) HistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 5. DutchNew York (State)History17th century. I. Title. II. Series: Early American Studies.

F122.1.S78M47 2013

974.7'02092dc23 2012038311

To

Virginia

PREFACE

The Outcast

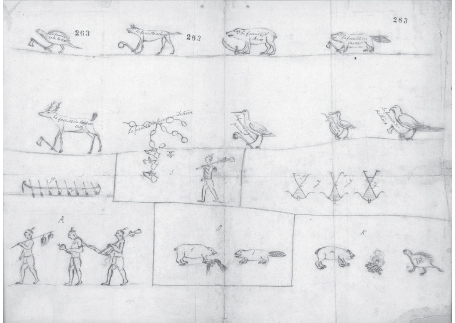

A haunting representation of Peter Stuyvesant rests among the documents relating to New Netherland. Stylistically it is similar to a line drawing. Spare, sensuous, and provocative, it is like a simple piece of graffiti. It is only fortynine words.

Stuyvesant is described as a captive. He is a lone figure being driven across the land with his hands bound behind his back. Nothing indicates the cause of his enforced journeying. Whatever his past in the country from which he is being driven, it is over. His future is commented on. His journey could end in one of three outcomes. He might simply be banished. Or, should his captors become impatient and see no value in him, he might be killed. But if, wherever he finishes up, he lives quietly, that would be allowed. He could remain in his own house and on his land, like any other man.

The tethered figure would have been known to local natives, some of whom were present to hear the description (Figure 1). He has a wooden leg. Whether this had previously inspired a sense of awe in them or aroused an uneasy awareness of something specially chosen about this figurea strange version of a manis hard to tell. They did notice it. And often other natives took the opportunity to refer to it. For seventeen years, the defeated and humiliated outcast had been the director general of Dutch New Netherland. The storymakers preferred to call him just Stuyvesant.

The image of rejection and loss is an accurate one. It was constructed on January 1, 1664, just eight months before an English fleet entered the harbor of New Amsterdam and forced the surrender of the city and province. A number of Englishmen had gathered at the Long Island village of Vlissingen (Flushing) in order to convince nearby natives to sell them tracts of land previously sold to the Dutch. They warned that many Englishmen were soon coming from overseas in three ships. The Dutch would be made to leave. The lands would become English: best now to be on the winning side.

Figure 1. Indian Warriors Returning with a Captive. Copy of Iroquois (probably Seneca) pictograph, circa 1666. Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

At that point, the Englishmen personified the loss of New Netherland in the figure of Stuyvesant. If Stuyvesant tried to do anything, the men told the natives, they would bind his hands on his back and send him out of the country or kill him, but if he kept quiet, it would be well and he might remain in his own house and on his land, like any other man.

They knew the image would evoke scorn. It would resemble the visual impersonations occasionally drawn by the natives themselves (Figure 2). The powerlessness of the man is easily read. His body wears three markers of defeat and loss. Each is within the possible experience of mid-seventeenth-century North Americans. He is chained or bound with ropes. He is forced to be on the move. He is subjected to captors who will finalize his fate but are presently enjoying his suffering and in no hurry to do so.

Figure 2. Indian Deed for Staten Island, July 10, 1657. Berthold Fernow, ed., Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York, vol. 14. Albany, N.Y.: Weed, Parsons, 1883.

The final months of Stuyvesants administration had been a series of losses. Councilors and subordinate officials had lost confidence in his ability to administer the province and guarantee its security against the neighboring English and natives. In Hartford, Connecticut, officials were refusing him the right to the title of governor. And why not? They were already dismissively declaring that they knew no New Netherland. By the early 1660s, it was clear that he had lost the loyalty of English Long Islanders. In 1664, he showed himself unable to maintain his authority over outlying Dutch settlements. This was especially evident when he most needed such towns as Beverwijck (Albany) and Wiltwijck (Kingston). In the desperate days preceding the English attack, his efforts to draw together an assembly of representatives of the towns had failed. His military position was close to impossible. He had repeatedly failed to convince the West India Company that the garrison on Manhattan Island was in serious need of reinforcements should an English attack occur.

When the English fleet finally arrived in late August, Stuyvesants efforts to mount defenses around New Amsterdam failed miserably. Diplomatic overtures to the fleets leaders were equally useless. They were flung back in his face. His surrender of the province was a reluctant but inevitable acquiescence to too few resources, too little loyalty, and a loss of confidence in his leadership. In its own way, the Englishmens bit of graffiti simplified all the history that has been made of the capitulation and subsequent transformation of New Netherland to English rule.

In 1667, he was found guilty of negligence and dismissed. His superiors conceded, however, that if he lived quietly, he could, wherever he chose to reside, remain in his own house on his land, like any other man.