EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Daniel K. Richter and Kathleen M. Brown, Series Editors

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Copyright 2006 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Merwick, Donna.

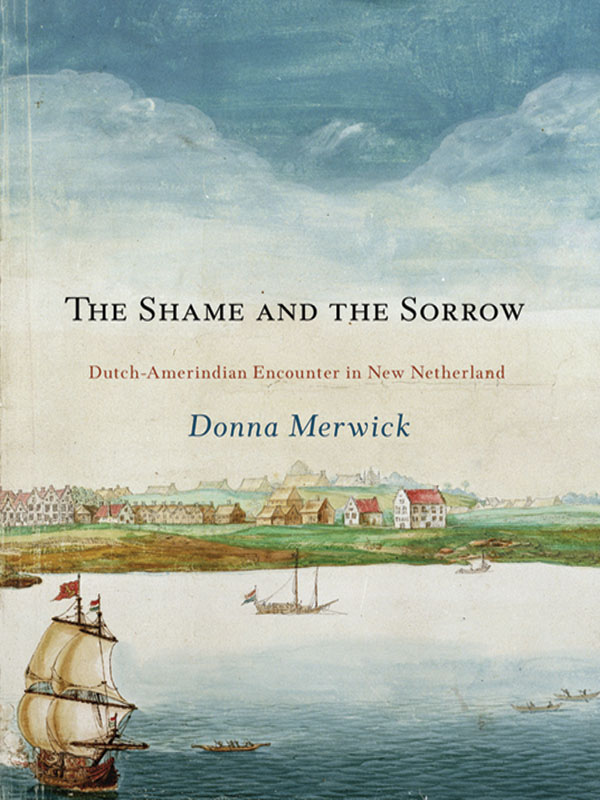

The shame and the sorrow : Dutch-Amerindian encounters in New Netherland / Donna Merwick.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-3928-7

ISBN-10: 0-8122-3928-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. New York (State)HistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 2. New NetherlandHistory. 3. Indians of North AmericaNew NetherlandHistory. 4. Indians of North AmericaWarsNew Netherland. I. Title. II. Series.

F122.1.M53 2006

974.7' 02dc22

2005055043

Soundings

This is the island (

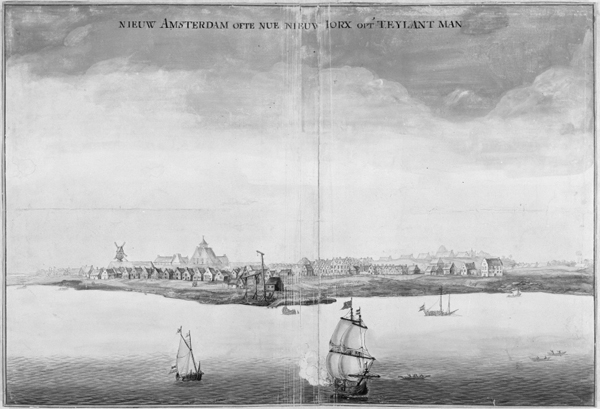

The island hides the land behind it. The continent that we know to be there and to which the island is offshore is given no hint of presence. Perhaps we are to think that enough presence is here, here on the ribbon of land between the wilderness of the sea and that of the continent inshore. Perhaps we are to think that the continent is somehow less valuable than the island. Certainly, the houses have resolutely turned their faces from it. Perhaps alongshore is better than inland.

There is an inland, and it is not as serene as the narcotic beauty of the watercolor would have us think. The town is, after all, not outside time but set in history. We know that the artist sketched it around 1664 to depict the early 1650s. We've come to know something about the houses along the strand, something about the warehouses, the fort, and the windmill. Of this maritime people, we've now written life histories. We can give accounts of their politics and the ways of their daily lives. We know that there were also those whom these alongshore people distinguished from themselves by calling them inlanders, natives. Here, in this scenery, the artist has given them only an incidental presence. A few paddle in open skiffs toward a vessel that is releasing a volley of fire to signal its departure from the harbor. It flies a Dutch flag. Perhaps the inlanders intend to trade. They appear to proceed without fear.

Fear is, in fact, the last thing this seascape wants to convey. There are no signs of conflict, neither in the tranquil present nor left over from earlier years. No rubble of stone or wood, no older foundation stones tell us that this waterfront land was won from another people, those who called this place the island of the hills. Nothing says that there is still violence between the islanders and inlanders. Like the harbor, the marginal lands that encompass it are all but empty. Set to the left and right, they peter out into lowlands and beaches, bleached out and uninhabited for miles and miles, as far as the eye is given to see. No one is shown farming beyond the town, neither the alongshore people nor the natives. No one toils in woodlands. There is a term that these shore people like to use for their settlements in such places: quiet possession. Surely this is as quiet as quiet possession comes.

Yet being set in history, time will not let the dreamlike atmospherics of this place go undisturbed. Being the view of a real alongshore town rather than a make-believe one elicits questions about presences and absences. What strange thing is the artist saying, what interpretation is he offering in declining to give any indication of the continent to which this place is only marginal, to which it is, or seems, only an entrept? Even if he is following an artistic protocol, why is he satisfied to sketch a town that wants only adjacencyadjacency to the sea before it and to the continent beyond?

Of course, before Europeans first sighted it, this place had been interpreted. But now ordinary sailors were making sense of it as they hazarded closer and closer to shore, terrified of death on hidden rock ledges or shifting sandbars. They explored the edge of the New World with what the Dutch called a dieplood and the English a dipsey lead. A sixty- to seventy-pound weight attached to perhaps six hundred feet of line, the dieplood let them test the depth of the waters. But even more. Tallow or soap secured in its concave end allowed them to gather traces of bottom sand or blue shells. Before their feet touched shore and before they erected their shore forts, the dieplood touched the indigenous Americans' ground.

Our artist has denied us of some of the raw materials we might want for interpretation. He has not, for example, included the forests that covered much of this place, Manhattan Island, in the early 1650s. The Europeans and natives both depended on wood for their survival. They sawed or bent it into shape for dwellings; they burned it for fuel. They twisted and turned it into the ribs of boats and rigging.

Once set ablaze, wood was also the cheapest resource Europeans and natives had for killing one another. They themselves told stories about it. In the mid-1630s, about fifteen years before the scene our artist hoped to catch, a group of natives encountered some Englishmen. They met along another waterside, not far from the island and in the Connecticut country, already claimed by both the Dutch and English who were trading there. Agitated by some presentiment of danger, a native cried out, What Englishmen, what cheerewill you cran us? Cran may have been a corruption of the Dutch word kwalm, meaning dense smoke. In English, it referred to an iron arm built for cooking over an open fire. Here, it meant, Will you kill us by setting our village ablaze and burning us alive?

Untold numbers of Algonquian-speaking men, women, and children died when Europeans set their villages on fire. During the same years, countless New Netherlanders died in fires set by natives. First it happened around Manhattan Island and then along nearby coasts. It was not just that fire was more easily available for killing than musket balls. It was so much more destructive. It could consume and destroy wildly: inhabitants and their houses and barns, stores of supplies, boats, animals, and sometimes all the crops standing in a field. For powerful bands of menMohawks over Esopus, Dutch over Raritansthe power to torch a village was an extortioner's tool. Before it leaped from brands and torches, fire fueled their protection rackets: show yourselves to be on our side; otherwise, we cannot ensure your safety against burning, not at the hands of your enemies or our own. The Europeans had learned these war techniques in their homelands. So had the Mohawks in theirs.