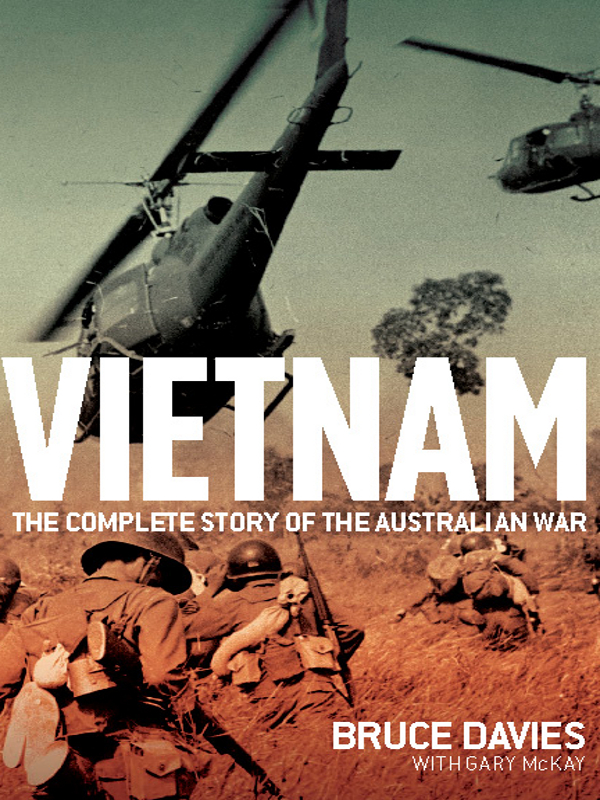

VIETNAM

VIETNAM

THE COMPLETE STORY OF THE AUSTRALIAN WAR

BRUCE DAVIES

WITH GARY McKAY

First published in 2012

Copyright Bruce Davies and Gary McKay 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 028 7

Internal design by Lisa White

Set in 11/16 pt Minion by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Vietnamese hate the Americans.

The Americans hate the Vietnamese.

The Americans hate the Americans.

The local Chinese are hated by the Vietnamese and the Americans.

The Australians hate everybody.

Lynn Ludlow

San Francisco Examiner

9 April 1968

CONTENTS

As well as costing the lives of nearly 500 Australians, 3000 physically wounded and many more with psychological injuries, the Vietnam War defined the adult lives of tens of thousands of Australians.

Younger Australians see Vietnam not so much as a war but as a destination for tourists or as a conference venue. The war for these touring Australians consists only of the titillation of visiting the Cu Chi tunnels on a day trip from Saigon. They are fed the line by young tourist guides, many of whom are the children of ex-South Vietnamese soldiers, that The American War was fought by the Vietnamese people against foreign aggression, forgetting the sacrifice of millions of South Vietnamese people, perhaps even the bravery of their fathers and uncles. It is always healthy to remember that the tanks which knocked down the gates of the Independence Palace on 30 April 1975 were part of a war of northern aggression. Each generation must see history from its own perspective and that applies as equally to young Australians as it does to todays Vietnamese living in what was once South Vietnam.

It is said that the victor writes the history but Bruce Davies assisted by Gary McKay MC, both veterans of this war, prove once again that we, the defeated, can and should have a voice. Indeed, Australian voices have been heard many times since our troops left Vietnam. Australians have written on battles and on operations, and most recently, the last volume of the official history has been published.

Bruce Davies is eminently qualified to add to the voices on Vietnam, having seen extensive combat in South Vietnam and been recognised for his gallantry and his service. He has written before on Vietnam, in the form of a history of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam, which almost spans the entire conflict, and the brilliantly told story of a small but vicious battle on a hill known as Ngok Tavak, where the North Vietnamese fought and defeated an Australian-led company of Nungs and a US Marine artillery detachment.

In this book, Vietnam: The complete story of the Australian war, Davies applies the forensic approach to history that he demonstrated in his previous books, but in a style which, while being both readable and academic, does not disguise his own, somewhat cynical view of the big political issues that shaped the war, and particularly the wars ignominious end.

I joined the Australian Army at the height of Australias involvement in this war, but finished my training too late to fight there. I read voraciously about the war from 1968 to 1971 as I prepared, but then only on and off over the next few decades. Vietnam was someone elses war. In the early seventies I served in Australia with Bruce Davies, at a time when his achievements and those of his comrades from Vietnam had still not become general knowledge.

As I served in units that had battle honours from Vietnam, I was exposed to our Veterans as they and I grew older. I still stand in awe of the type of tactical military operations that they conducted, and Davies book reminds us of these achievements. Regardless of who won or lost in Vietnam, it is fair to say that the Australian soldier, regular and conscript, fought well. The Australian soldier has never lost any war in which we have been involved. Wars are lost by civilian and military generals. Despite this, Davies has a balanced and realistic view of exactly how well our soldiers fought and our generals commanded, and is not overcome by the inevitable myths and legends that all wars produce.

As time went on after Australias withdrawal, Australia, its military and its government focused on other conflicts. Vietnam might have been for later generations someone elses war, but it still holds many critical lessons relevant to todays conflicts. I worked for a US general in Baghdad whose father, the commanding general of a US division, was killed in Vietnam. General George Casey took over in Iraq as the war deteriorated severely around us, and for the initial few months in the US Embassy in the Green Zone in Baghdad, the word on our lips was: This will not be another Tet.

The way that the US fought the war in Iraq, another militarily successful war with dubious strategic outcomes, was strongly and beneficially influenced by the US realisation that they had been soundly defeated in Vietnam. US generalship, the courage and professionalism of the US soldier and the ethics of how they prosecuted that war, benefitted immensely from the acceptance of failure in Vietnam. It was a shame that US political leadership did not learn as much as the military.

Over forty years of military service, I gained the impression that my army and certainly successive Australian governments and influential bureaucrats, did not learn the lessons of Vietnam. Our approach was coloured by the view that it was all the USs faultthey had lost the war. The popular lesson from Vietnam has now become, erroneously, that such wars were unwinnable, we should never again become involved in them, therefore there is no need to maintain a modern independent military in Australia.

But Australias involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan shows that, regardless of what popular critics might think of involvement in foreign wars as an ally of the US, Australian governments continue to see value in doing so. If Australian governments are going to remain aggressive and their soldiers continue to pay in blood, then we had better learn which are the right wars in which to become involved, and how to win them once involved. The real benefit of this book is not just as a well-written and researched history offered in a more concentrated form than the official histories, but as an object lesson in how to win and lose wars, especially from the point of view of a small ally in a big war. This book is a superb vehicle for learning the lessons.

Next page