All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

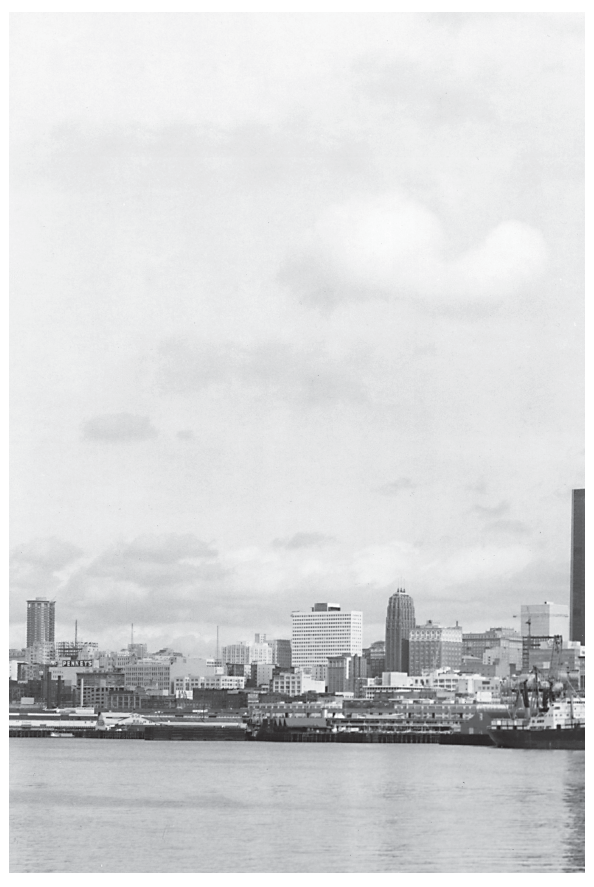

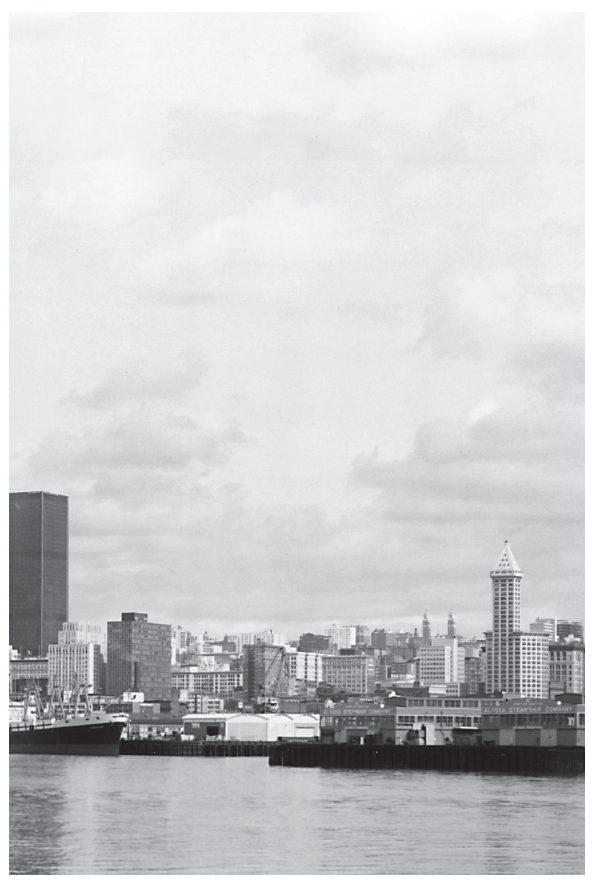

A FIRST-YEAR history grad student sat on the wooden planks in the left field bleachers in the bright May sun. The Mountain, Mount Rainier, was out. The Pilots were playing the Detroit Tigers in what would be one of the most exciting games of the year. The previous winter had seen heavy snow and then record cold in January and February that caused the student, who had moved from Southern California, to wonder about life in the Northwest. But the spring was a Puget Sound spectacular of blooms, long twilights, and gentle warmth. The newcomer was falling in love with Seattle. It was not Dodger Stadium, but the greens and blues of this pastoral scene made an idyllic setting for playing baseball. Seattle was a big city that did not seem to realize itand that was appealing. Traffic seemed light. The acknowledged ills of the city looked quaint: the police vice squad practiced vice. There was a plethora of neighborhoods all worth exploring. Most of the real problems were in abeyance. The economy flew pretty much on a single engine, but Boeing appeared to be going strong. There was racial inequality and consequent tensions, most evident on the University of Washington campus, but viewed through the lens of the Watts riots, race relations were less strained than in other large cities.

After forty years and a career as a historian spent away from Seattle, and then retirement to the Northwest, writing about that time, that city, and that team seemed like a worthy project. The warm glow of personal experience in the late 1960s and early 1970s is still evident at many points in this book. But the process of reading through the newspapers again, looking at the evidence, thinking about the leadership that put the Pilots in place and lost the team to Milwaukee, and then built the Kingdome,yields a story of greater complexity. Civic virtue is mixed with apathy and some selfishness. The inadequacy of those planks in the bleachers are as much a part of the story as the ballplayers on the greensward in the sunshine. Circumstances surrounding the loss of a team after one year might explain why the fifteenth largest market did not feel like a big city.

So this is a story of remembrance, but it is also a historical record woven out of research, thought, and analysis. Inevitably, such a work is not the product of a single writer. Plenty of colleagues, friends, editors, librarians, and archivists have lent a hand. Dona Bubelis of the Seattle Central Library spent considerable time working up a packet of research suggestions. At Seattle Municipal Archives, Anne Frantilla supplied valuable sources on the Pilots and Sicks' Stadium, while Julie Kerssen provided guidance in locating sources in the reorganized files. Janette Gomes led the way expertly through finding aids and retrieved scrapbooks and boxfuls of materials at the King County Archives, and Rebecca Pixler brought out an array of King County photos. James Copher at the Northwest Regional Branch of the Washington State Archives retrieved the records, more than once, of the lengthy trial that brought the Mariners to Seattle, and Philippa Stairs expanded my scope of research and retrieval at the Puget Sound Regional Branch. Carolyn Marr at the Museum of History and Industry and Nicolette Bromberg at the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections dug into their troves of images to help find illustrations for the book. Patrice Hamiter of the Cleveland Library made it much easier to find photos of William Daley. Tim Jenkins was enthusiastic and generous in sharing his knowledge and extensive collection of Pilots memorabilia.

I express thanks to those who were willing to talk with me, sometimes for hours. Bill Sears, Rod Belcher, Jim Kittlesby, Lew Matlin, and Eddie O'Brien of the Pilots provided context and much to consider in telling the team's story. James Ellis represented the perspective of civic leaders with grace. John Owen added his memories to his insightful Seattle Post-Intelligencer columns. John O'Brien, Slade Gorton, and John Spellman were willing to share information and perceptions that went well beyond the written records. I express my appreciation, as well, to Mike Fuller, the proprietor of the extensive website honoring the Seattle Pilots, where he shares interviews of those who have passed away.

Because a number of people have read through parts or all of themanuscript at various stages, the book is more streamlined, a better read, and burdened by fewer errors, and as any author should, I bear the responsibility for any errors that still exist. Kent Anderson read the first draft, caught some crucial mistakes, and suggested ways of condensing the narrative. John Findlay, who has been an encouragement from the outset, read several of the first chapters early on and proffered helpful advice on characterizing midcentury Seattle. Karen Anderson read the entire book and made helpful suggestions on enlivening the narrative. David Eskenazi, who probably knows more Seattle baseball history than anyone, has read much of the text, made corrections, supplied a raft of Pilots documents, shared his collection of photos, and given his moral support throughout the project. His assistance has been essential. Marianne Keddington-Lang has gone beyond the duties of an acquisitions editor, offering her vision and her counsel on how to bring this book to fruition. Laura Iwasaki, as copy editor, worked with remarkable diligence, precision, and empathy for the project. My daughter Julie Mullins was a willing in-house (literally) professional editor who did as much as anyone to make this a more tightly written, more readable work. My deepest thanks are to her for supplying her talents and her time.

Finally, it is not just those who have an impact on a book directly by assisting with research or lending their expertise and a keen eye that make such a project possible. Friends and, especially, family provide an atmosphere of encouragement that keeps an author going or furnish support that gives an author time to gather materials, write, and rewrite. And so it is with this work. Thanks to those who asked after the project over its years of gestation. Thanks to Julie and son, Michael, who knew the importance of completing the job. And I thank my wife, Edith, who has been with me from shortly after that first spring in Seattle, who loves the Northwest just as much or more than I do, whose patience is enduring and encouragement sustaining, and to whom I dedicate this book.

![Baseball Info Solutions. - The Bill James handbook 2014: [the complete up-to-date statistics on every major league player, team and manager through last season]](/uploads/posts/book/187296/thumbs/baseball-info-solutions-the-bill-james-handbook.jpg)