OTHER BOOKS BY D UDLEY P OPE

PUBLISHED BY M C B OOKS P RESS

The Lord Ramage Series

Ramage

Ramage & The Drumbeat

Ramage & The Freebooters

Governor Ramage R.N.

Ramages Prize

Ramage & The Guillotine

Ramages Diamond

Ramages Mutiny

Ramage & The Rebels

The Ramage Touch

Ramages Signal

Ramage & The Renegades

Ramages Devil

Ramages Trial

Ramages Challenge

Ramage at Trafalgar

Ramage & The Saracens

Ramage & The Dido

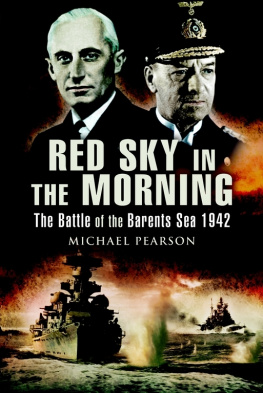

Nonfiction History Library

The Devil Himself: The Mutiny of 1800

The Battle of the River Plate: The Hunt for the

German Pocket Battleship Graf Spee

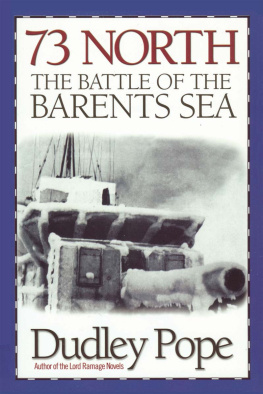

73 North: The Battle of the Barents Sea

Published by McBooks Press 2005

Copyright 1957, 1988 by Dudley Pope

First published in the United States by the Naval Institute Press

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. Requests for such permissions should be addressed to McBooks Press, Inc., ID Booth Building, 520 North Meadow St., Ithaca, NY 14850.

Cover: Ice covering the Onslows A and B turrets,

The Imperial War Museum

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pope, Dudley.

73 North : the Battle of the Barents Sea / by Dudley Pope.

p. cm.

Previously published: Annapolis, Md. : Naval Institute Press, [1988?]

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-59013-102-9 (trade pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Barents Sea, Battle of the, 1942. 2. World War, 1939-1945Arctic Ocean. I. Title: Seventy three North. II. Title.

D772.B37P66 2005

940.5429dc22

2004031027

Visit the McBooks Press website at www.mcbooks.com.

Printed in the United States of America

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

To A. and T. S. W.

Contents

Illustrations

A chart showing the convoys route appears on .

Track charts showing the progress of the battle appear on .

Illustrations pages courtesy of Planet News Ltd.

Foreword

by Admiral of the Fleet Lord Tovey, G.C.B., K.B.E., D.S.O. Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet 1940-1943

T HE B ATTLE OF THE B ARENTS S EA was one of the finest examples in either of the two World Wars of how to handle destroyers and cruisers in action with heavier forces. Captain Sherbrooke saved his convoy by going straight in to attack his far heavier enemy, using his guns to do what damage they could but relying on his torpedoes, the real menace to the heavy ships, to deter them from closing the convoy.

Sherbrooke knew the threat was lost once his torpedoes were fired. When in position for firing he turned his ships to simulate an attackthe mere threat was sufficient to persuade the enemy to break off their attack.

In spite of the smallness of his force Captain Sherbrooke had not hesitated to detach two destroyers to cover the convoy from possible attack from the other side.

As Sherbrooke went in to attack, the Commodore turned his convoy away and it was quickly covered by smoke from the Achates. Throughout the action the Commodore handled his convoy with great skill.

Smoke-laying may not appear a very exciting way of fighting but I know few things more unpleasant than being fired at when you cannot shoot back. Apart from preventing the enemy getting a sight of the convoy, there is always the chance of a torpedo attack developing out of the smoke. The sinking of the smoke-layer is essential if the enemy is to get a chance of damaging the convoy and the Achates was constantly coming under heavy fire, but she stuck to her job right up to the time she sanktruly a noble little ship and company.

When Captain Sherbrooke was himself put out of action his second-in-commandand when his wireless failed, the next in commandcontinued the same tactics.

It was no sudden inspiration that Captain Sherbrooke acted under; he had thought it all out before sailing and had discussed every move with his subordinate commanders and the Commodore of the convoy, and I am sure he would be the first to pay tribute to the previous training given to his flotilla by Captain Armstrong, whom he had very recently relieved.

I doubt if many who did not actually serve in the cruiser escorts of the Russian convoys appreciated the extremely difficult conditions under which they operated. Normally when a convoy had completed only a quarter of its trip it had three or four enemy submarines in its vicinity. Later there might be twelve or more.

To close and sight the convoy was, therefore, asking to be torpedoedtwo cruisers were lost in this way. Wireless silence was necessary for escorts and the convoy to avoid the enemy detecting their position or, if they had been lucky enough not to have been sighted, of giving away the fact they were at sea. Wireless signals could be made only when it was obvious the enemy knew their position or a ship had been detached and was some distance from the convoy.

So cruisers seldom knew at all accurately the position of the convoy they were escorting. Is it to be wondered at that Admiral Burnett closed that very suspicious radar contact on his way to support the destroyers?

Admiral Burnett had more experience than any other officer in escorting Russian convoys and was in more actions in their support, finally shepherding the Scharnhorst to her destruction by the Duke of York, flying the flag of Admiral Fraser, and her destroyers. I never knew Admiral Burnett to take anything but the right action promptly and with the greatest gallantry.

Dudley Pope tells his fine tale magnificently with no embellishments, and the way he has woven in the German information and the personal experiences of those concerned makes thrilling and fascinating reading.

The Battle of the Barents Sea was an action of which we can all be enormously proud, but it was only one of the many convoys that were run and not all were so successful. Altogether they carried to Russia a total of 428,000,000 worth of material, including 5,000 tanks and over 7,000 aircraft and also large quantities of high explosives and high octane spiritunpleasant cargoes when hit by a torpedo.

Sixty-two outward-bound merchant ships were lost while twenty-eight of those homeward-bound failed to arrive. Two cruisers, six destroyers, three sloops, two frigates, three corvettes and three minesweepers were sunk with the loss of 1,840 officers and men.

For at least twelve days the convoys were liable to submarine attack; in the summer for six days they were within range of ever-increasing air attack. In winter they experienced bitter cold and some of the worst weather ever met with, as well as dense fog, which no sailor likes. As with other convoys, there was the ever-present risk of being torpedoed, but with the water never far off freezing the hope of ever being picked up alive was very slim.

The officers and men of the ships in convoy and of their escorts were heroic. Masters of ships, some over seventy, men and boys only sixteen years old, after having their ships sunk under them sometimes two or three times, came back for more and insisted on ships going to Russia. I hope that perhaps one day Dudley Pope will tell the story of the Russian convoys as a whole as some tribute to the gallant men who, while never catching the spotlight, gave such service.

Next page