Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

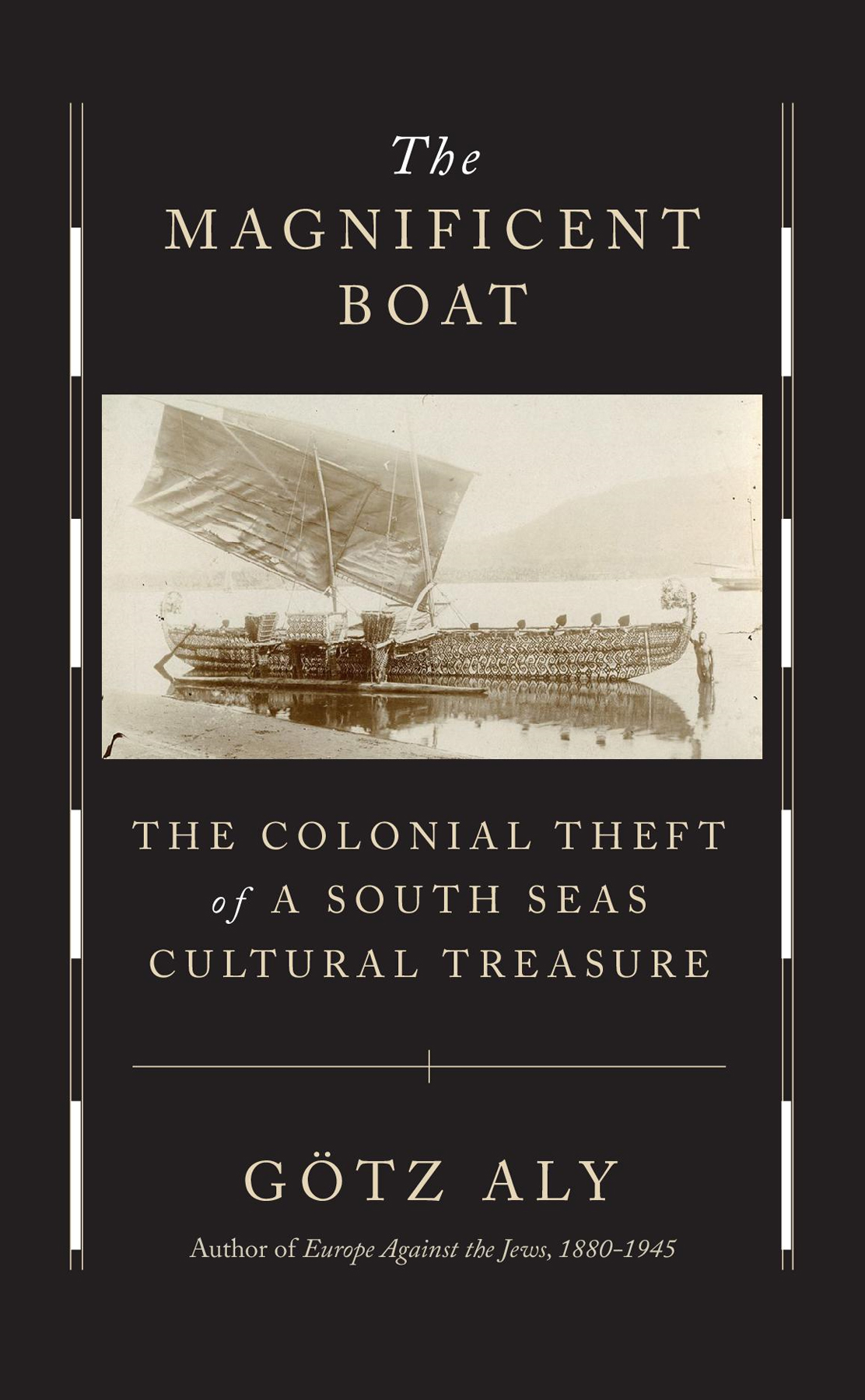

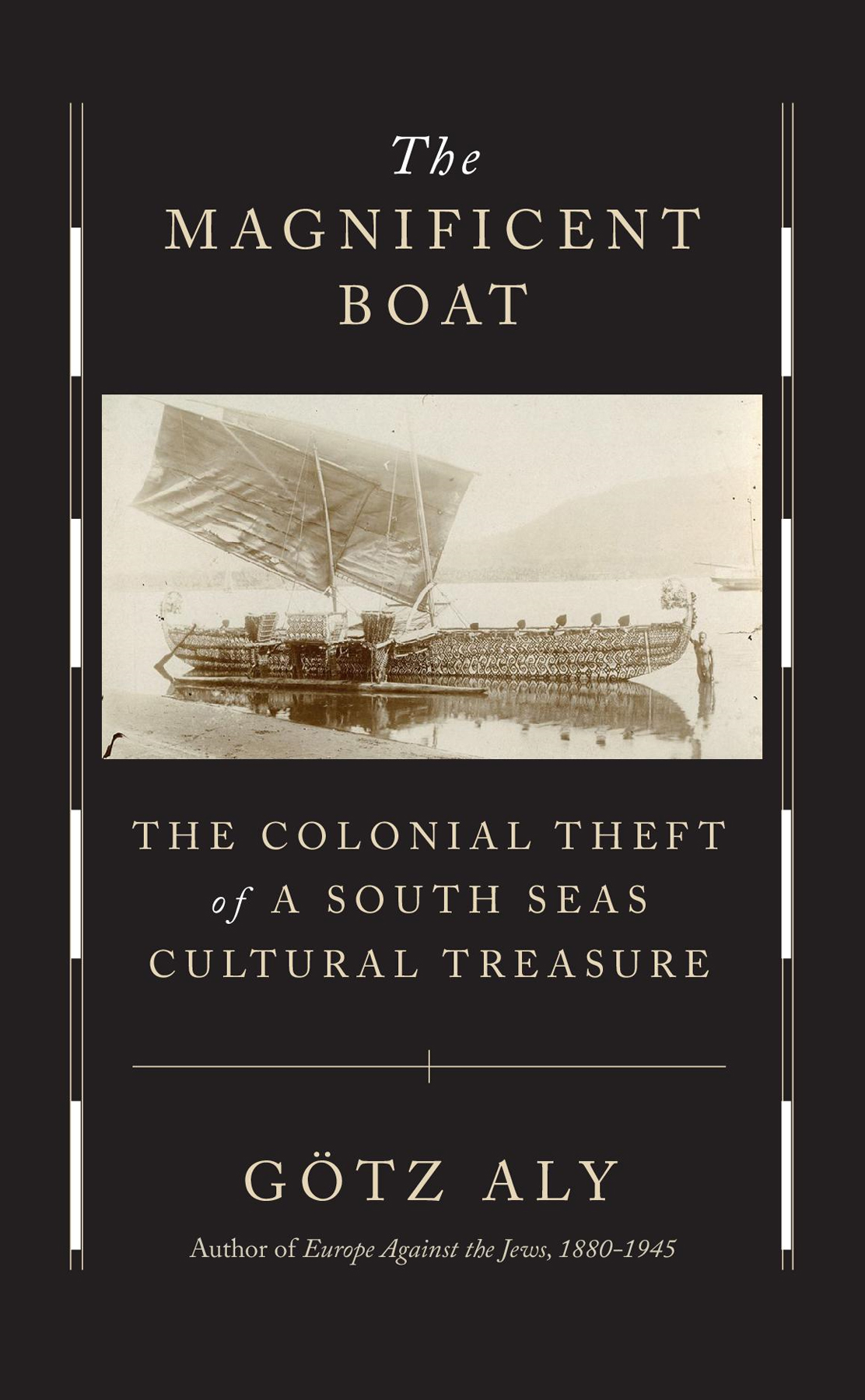

The Magnificent Boat

The Colonial Theft of a South Seas Cultural Treasure

GTZ ALY

Translated by Jefferson Chase

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

2023

Copyright 2023 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Originally published in German as Das Prachtboot: Wie Deutsche die Kunstschtze der Sdsee raubten, Copyright 2021 by S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main

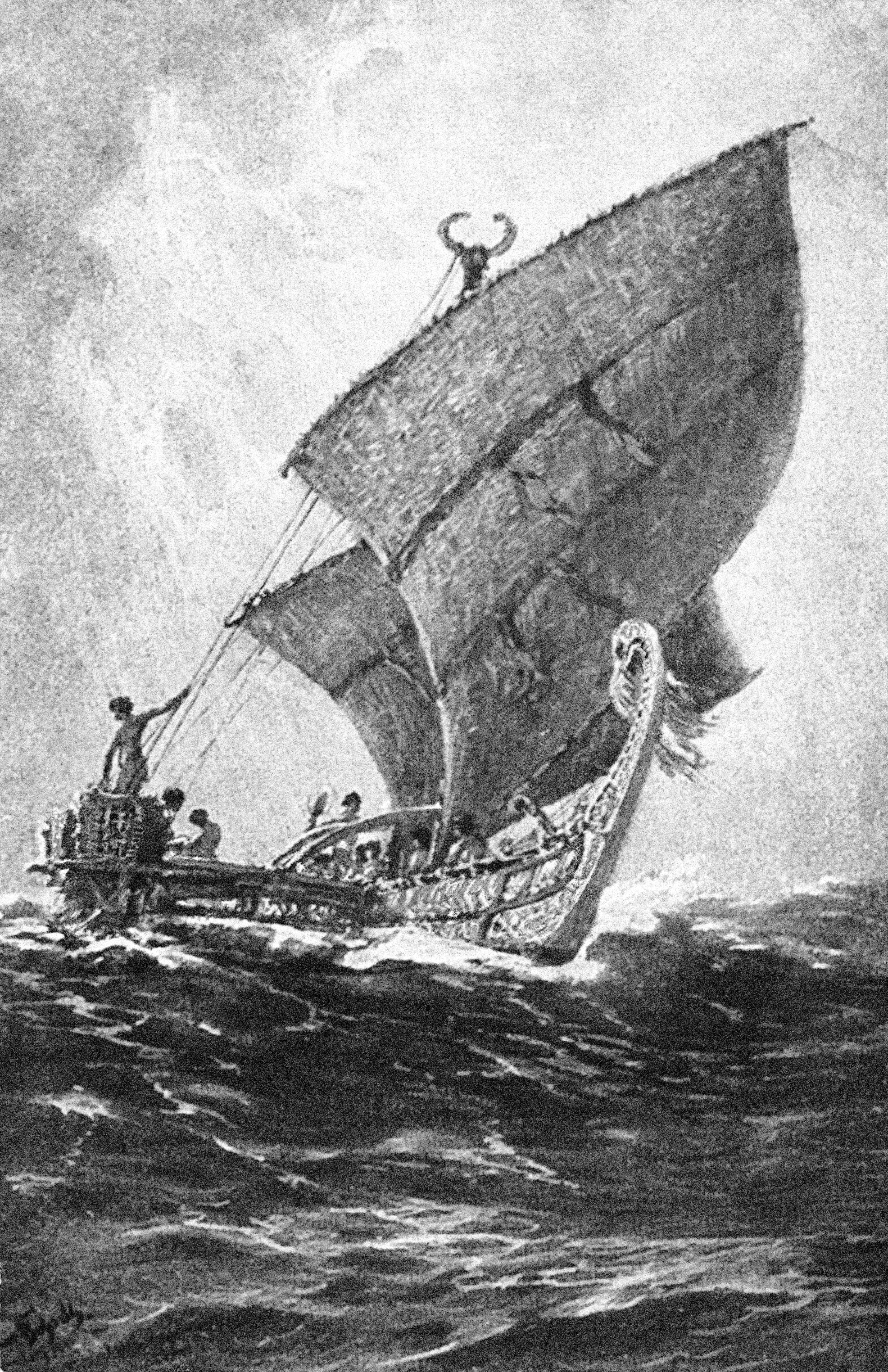

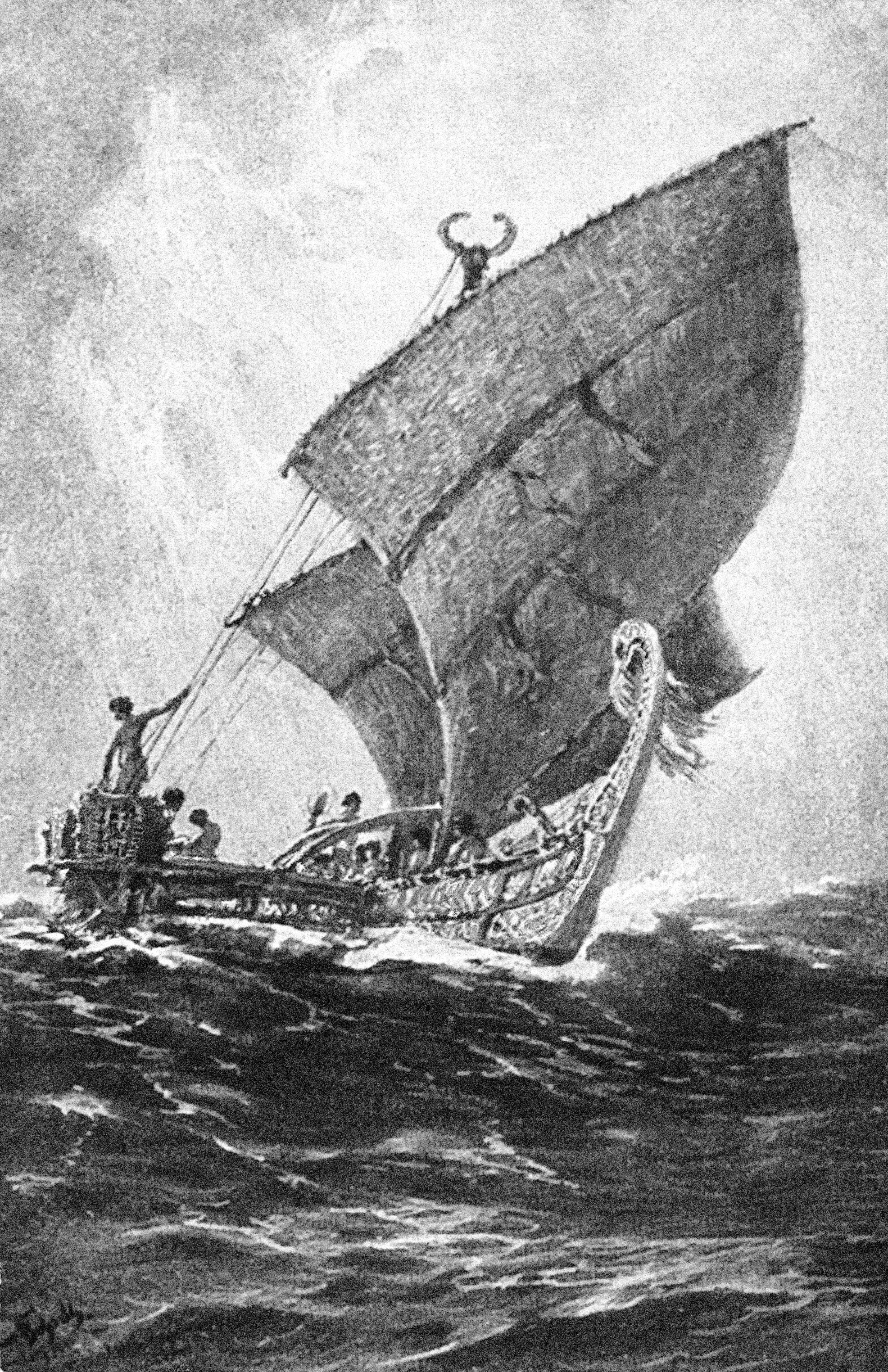

Frontispiece: Painting of the Luf Boat sailing the open seas by maritime artist Hans Bohrdt, from a 1916 postcard. The reverse side of the card reads: The last boat from Agomes [Luf] Island in the South Seas, published by the Kolonialkriegerdank [Colonial Warriors Gratitude Association], a registered association supporting former colonial warriors of the army, navy, security, and police troops and those they left behind.

Cover image: Reproduced from Richard Parkinson, Dreissig Jahre in der Sdsee (Stuttgart: Strecker & Schroder, 1907), plate 30.

Cover design: Oliver Munday

978-0-674-27657-4 (cloth)

978-0-674-29322-9 (EPUB)

978-0-674-29319-9 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Aly, Gtz, 1947 author. | Chase, Jefferson S., translator.

Title: The magnificent boat : The colonial theft of a South Seas cultural treasure / Gtz Aly ; translated by Jefferson Chase.

Other titles: Prachtboot. English

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2023. | Originally published in German as Das Prachtboot : wie Deutsche die Kunstschtze der Sdsee raubten, Frankfurt am Main : S. Fischer Verlag, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022031710

Subjects: LCSH: Luf-Boot (Boat) | Cultural propertyDestruction and PillageGermany. | Cultural propertyDestruction and pillagePapua New Guinea. | Boats and boatingPapua New GuineaHistory. | Papua New GuineaAntiquities.

Classification: LCC DU740.3 A5913 2023 | DDC 995.3dc23/eng/20220719

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022031710

In general and without exaggerating, we can say the following about a great many colonies: A large percentage of the work of European officials, officers, merchants, and researchers is directed toward brawling, looting, vandalism, arson, and murder.

SIEGFRIED LICHTENSTAEDTER, Kultur und Humanitt (Culture and Humanity), 1897

Contents

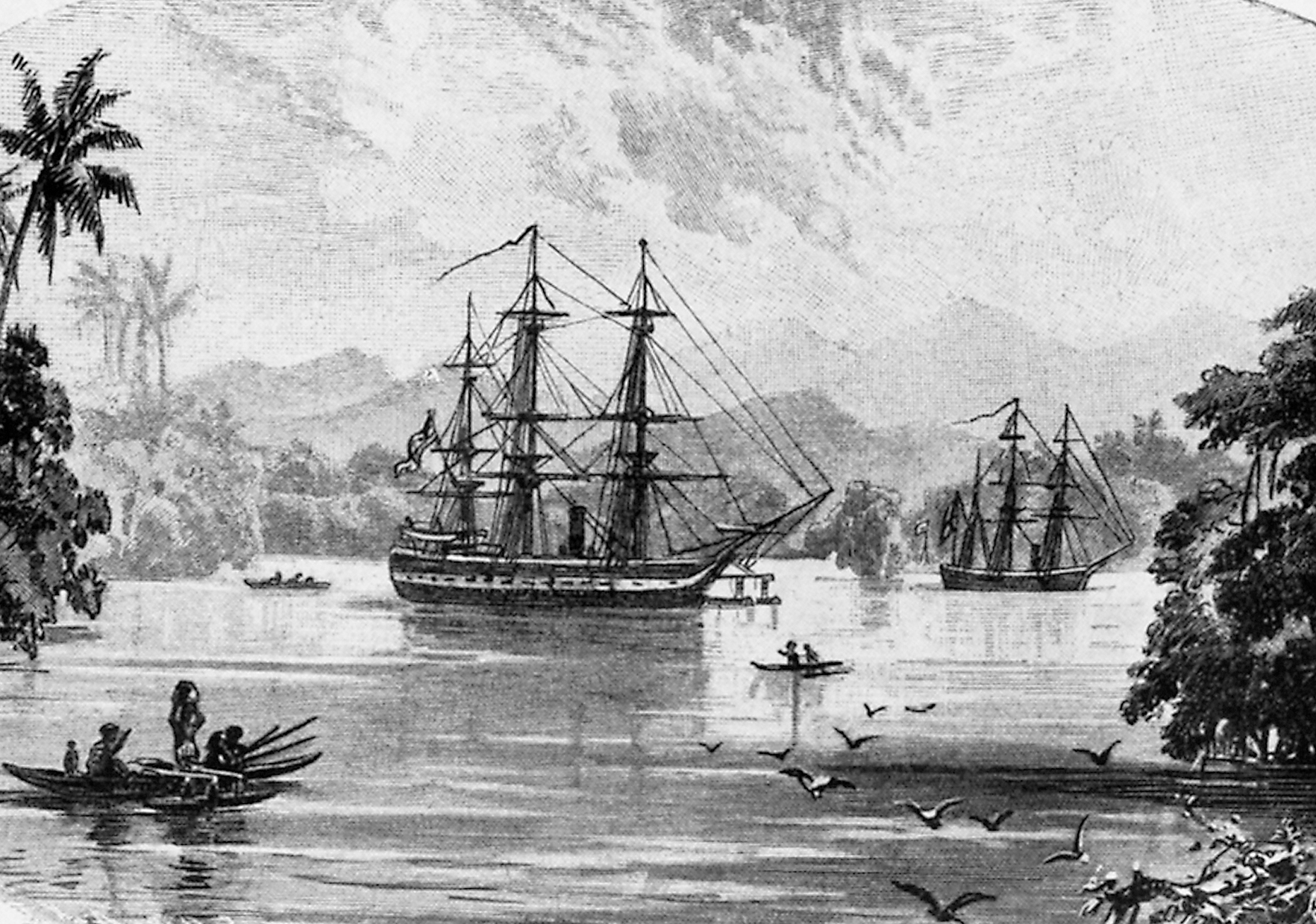

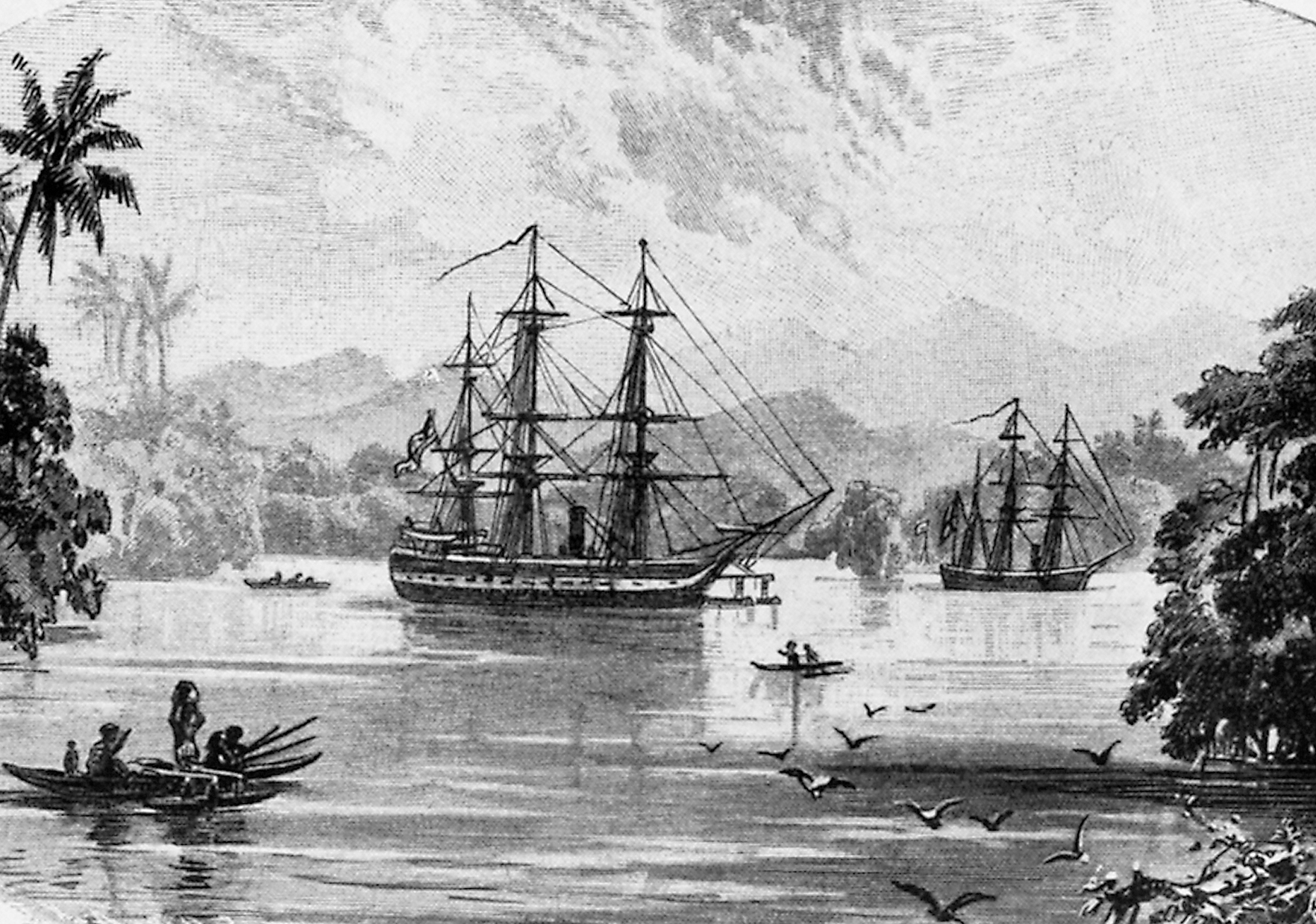

In late November 1884, the crews of the German navy corvette Elisabeth and the gunboat Hyena dropped anchor in Astrolabe Bay and raised the Imperial German flag over New Guinea. On board was the navy chaplain Gottlob Johannes Aly. A short time later, the German administration town of Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen (todays Madang) was founded.

F or quite some time, the Bismarck Archipelagoa group of islands off the northeastern coast of New Guineahas been on my radar screen as a historian. The reason is that my great-granduncle Gottlob Johannes Aly served in the Imperial German Navy as a chaplain and took part in the colonial subjugation of the archipelago in the 1880s. One of the islands was in fact named after him. I knew this even as a child. But like most of his countrymen, Pastor Aly didnt talk about conquering or subjugating; at most he might refer to occupying, but usually he spoke of civilizing, missionizing, and protecting.

The German colonial possessions near Australia included the northeastern quarter of the main island of New Guinea as well as the Bismarck Archipelago. The colony, which existed, at least de facto, from 1884 to 1914, was known as German New Guinea. Mount Wilhelm, the highest mountain (at around 4,500 meters), was named after Chancellor Otto von Bismarcks son and is still known by that name, and the Bismarck Sea has also kept its name internationally. Today, the former German colony, together with what used to be the British southeastern part of the island, make up the nation of Papua New Guinea, which was founded in 1975.

During their thirty-year reign, the colonists of German New Guinea established plantations totaling around 35,000 hectares. Exports included phosphate, gold, caoutchouc (natural rubber), cocoa, pearls, mother-of-pearl, and trepang (dried sea cucumber, or bche-de-mer), which is considered a delicacy. But the most important export product was copra (dried coconut), which was used to make margarine and soap.

Plantation owners and merchants wielded the sort of executive power normally reserved for governments. They officially enjoyed a broad right to physically discipline their workers, impose monetary fines upon them, and even confine them to special spaces in chains or not. In reality, they had far greater leeway. Colonists who stole from or killed savages, raped women, or kidnapped young men for forced labor usually had no fear of being punished.

Such latitude was entirely in keeping with the German colonial endeavor Bismarck had laid out before the German parliamentthe Reichstagin the summer of 1884. Over and over, colonial policy prioritized mercantile initiatives and permeation of more and more territory and was backed by state and military support. The favored means of enforcing colonial interests were so-called punitive expeditions led by Imperial German gunboats. Bismarck spoke in convoluted but nonetheless unambiguous form of the merchants abiding sovereignty derived from the German Empire, which exclusively served the free development of German enterprises.

German merchants, agriculturists, pioneers, and missionaries could thus call in the military whenever natives refused to obey or rebelled against their new masters. Both the rebellions and the interventions happened repeatedly. Because of the great distances involved, colonial German punishmentsin reality, acts of revengewere often carried out months or even years later. Those who suffered were mostly the innocent victims of military actions that got out of hand and resulted in massacres. Nonetheless, such actions were regarded as necessary for making examples of rebels, preventing uprisings, and reinforcing German power and interests. German newspapers reported extensively on the massacres, which they portrayed as nothing at all out of the ordinary. The granting of state powers to profit-oriented entrepreneurs remained controversial, but that was the rule throughout German New Guineaalthough it was obvious, given the gigantic distances and relative dearth of colonists, that selfishness, greed, violence, and capriciousness would inevitably flourish unchecked.

The colony was expanded through the addition of a number of far-flung Micronesian islands in 1899, after which voyages by sailing schooners across the territory of German New Guinea, 3,000 kilometers east to west, could take up to fifty days. In early 1914, for every 500,000 Indigenous people, there were 1,130 white people, including 247 women and 113 children. The statistics also listed 102 half-breeds. Most of the white people were German citizens. A third of this tiny ruling class were missionaries; the others were farmers, merchants, sailors, machinists, technicians, and officials. Despite intense recruitment efforts, few settlers were lured to the mysterious world of the South Seas. Those who worked there had pledged loyalty to the German flag and lived in constant fear of being attacked. Countless stories were told and constantly embellished about murdered traders and slavering cannibals who roasted and devoured their fellow human beings. The fear of such horrors, combined with the colonists own material interests, led to military aggression and everyday violence against Indigenous people, with their far greater numbers and vastly superior knowledge of the region.