The Sixties

Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy,

and the United States, c.1958c.1974

Arthur Marwick

This electronic edition published in 2011 by Bloomsbury Reader

Bloomsbury Reader is a division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square, London

WC1B 3DP

Copyright Arthur Marwick 1998

The moral right of author has been asserted

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication

(or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital,

optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written

permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this

publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

ISBN: 9781448205738

eISBN: 9781448205424

Visit www.bloomsburyreader.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for

newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

Preface

Without the sources contained in archives and libraries the historian is nothing. Without archivists and librarians to guide him/her the historian is a blunderer, high on purpose, low on achievement. The archives I have used are listed at the end of this book. But I begin here with an expression of my immense debt of gratitude, for the warmth of their welcome as well as their unstinted assistance, to the archivists and librarians at: the Mississippi Valley Collection, Memphis State University; the Memphis and Shelby County Library Special Collections; the University of Mississippi Library Special Collections; the University of California at Los Angeles Library Special Collections; the Stanford University Library Special Collections; the Library of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Stanford University; the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley; the San Francisco Public Library Reference Section and Department of Documents; the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library; the Cornell University Library Division of Manuscript Collections, Ithaca, New York; the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Grayson History Research Center, University of Minnesota Libraries, St Paul (a visit which goes back to the seventies); the Institut Franais dHistoire Sociale at the Archives Nationales, Paris; the Centre de Recherches, Histoire des Mouvements Sociaux et du Syndicalisme, Paris; the Muse Nationale des Arts et Traditions Populaires, Paris; the Maison de la Villette, Paris; the Archivio Diaristico, Pieve Santo Stefano, Tuscany; the Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Milan; the Istituto Ferruccio Parri, Bologna; the Library of the Universit dei Stranieri, Perugia; the Biblioteca dei Deputati, Rome; the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick Library; the National Library of Scotland; and the old British Library Reading Room. It is always a pleasure to work at the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris and at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Rome, the latter, because of its friendly bar, being the only library I know where it is easier to order a drink than a book. The New York Public Library, to use the local idiom, is something else. Nearer to base, Tony Coulson at the Open University Library has always come up with the answers I needed.

Along with archivists and librarians, historians need patient, self-crucifying colleagues. Professor Pierre Sorlin of Paris and Bologna and Professor Dan Leab of New York went far beyond the call of comradeship in battling through a massive earlier draft of this book, annotating practically every page, every paragraph, every phrase. The book has benefited immeasurably from their ministrations, though I fear I sometimes continued to go my own way. For some very shrewd and helpful comments I am grateful to Henry Cowper, Simon Sadler, Robert Rowland, and my colleagues on the Open University Sixties Research Group. I should also make special mention of Dr Robert Lumley of University College, London, who not only gave a sparkling and informative talk to the Open University seminar, but provided me with important bibliographical information for Italy. For photocopies of important periodical material, I am indebted to my colleague Dr James Moore.

Trying out ideas in seminars and lectures is a vital element in the process by which history books come to be produced. I have had my thoughts corrected, clarified, extended, not just at the Open University seminars but in discussions at Memphis State University, the University of Perugia, the University of Reykjavik, and at Bristol, Cambridge, and Edinburgh universities. In communicating ones ideas and in receiving corrections one employs that wonderful human tool, language: we use language, language does not, as some theorists insist, use us.

All sources, including statistical ones, are suspect; but practically every source has some unique strength as well as many weaknesses. Much of my search has been for the responses of individuals and families in all classes to the cultural revolution of which they were themselves the vital component, in letters to each other, to the press, to their MPs and Congressmen, in diaries, in memoirs. Where what they say is congruent with the frameworks established by the more quantitative sources, I have quoted them. I have made much use of magazinesfor teenagers, for the aspiring lower middle class, for women, for prosperous African-Americans: undoubtedly the owners and editors had their own agendas; but so did readers. Because of problems of access and the difficulty of achieving consistent coverage over the four countries, I have made much less use of television broadcasts than I would have liked (here, as elsewhere, there is still plenty of work for others to do). Oral history, recorded scientifically by other scholars, has been very useful; I have not tried to set myself up as an oral historian, just as I have striven not to rely on my own recollections. Photographs, cartoons, etc. are primary sources too. Like all sources they have to be critically analysed and collated with relevant contextual information. I have tried to do this in my captions.

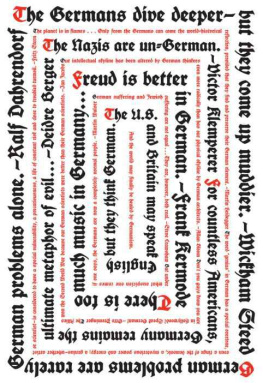

For a piece of comparative history, Britain, France, Italy, and the USA make a good choice, but, quite frankly, I could not seriously consider including Germany because my knowledge of German extends little beyond reading menus and ordering food and drink. The importance of comparative history was driven home for me by an American who remarked: Say, I never knew you guys had a sixties over there.

The immense tasks of preparing the constantly revised latest drafts, devising systems to cope with these and with the protracted process of tracking down missing references, and preparing the finalized text for handover to the publishers were carried through with great patience and skill by Margaret Marchant, to whom I also owe a great debt. For indispensable work on early drafts I would like to thank Mandy Topham, Wendy Clarke, and Janet Andrews.

As the Open University Research Committee denied me funds for my researches, I largely financed them by taking visiting professorships at Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee, and at the University of Perugia. I have the warmest memories of my sojourns at both places, and I received enormous help from both my American and Italian colleagues: my thanks also to them, and in particular to Professor Piero Melograni. I am very grateful to the Arts Faculty Research Committee, which not only financed my original travel arrangements but made possible several subsequent visits to the French and Italian archives and libraries, and to Warwick and Edinburgh.