European Dictatorships,

19181945

Third edition

European Dictatorships, 191845 surveys the extraordinary circumstances leading to, and arising from, the transformation of over half of Europes states to dictatorships between the First and the Second World Wars. From the notorious dictatorships of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin to less well-known states and leaders, Stephen J. Lee scrutinizes the experiences of Russia, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal and central and eastern European states.

This third edition has been revised throughout to include recent historical research, and has expanded sections on the setting for dictatorships and comparisons between them. There are more detailed discussions of Mussolini, Hitler and Holocaust and an entirely new survey of Turkey. This edition also includes a completely new chapter on types of dictatorship which explores both the meaning and the widely different forms it can take.

Extensively illustrated with photographs, maps and diagrams, European Dictatorships, 19181945 is a clear, detailed and highly accessible analysis of the tumultuous events of early twentieth-century Europe.

Stephen J. Lee was formerly Head of History at Bromsgrove School in Birmingham, UK. His previous publications include Russia and the USSR (Routledge, 2005), and Hitler and Nazi Germany (Routledge, 1998).

European Dictatorships,

19181945

Third edition

Stephen J. Lee

First published 1987 by Methuen & Co. Ltd

Second edition published 2000 by Routledge

Third edition published 2008 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Ave, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1987, 2000, 2008 Stephen J. Lee

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form of by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been applied for

ISBN10: 0415454840 (hbk)

ISBN10: 0415454859 (pbk)

ISBN13: 9780415454841 (hbk)

ISBN13: 9780415454858 (pbk)

Again, for Margaret and Charlotte

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Figures

Dictatorships

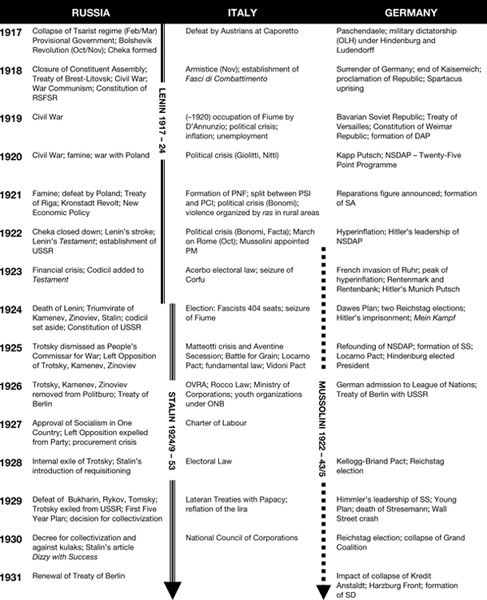

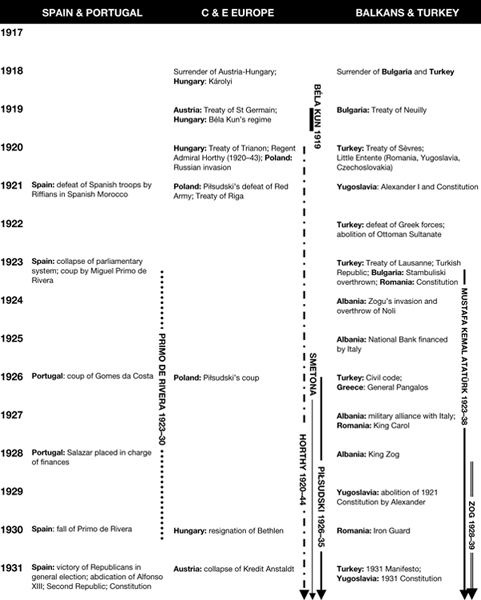

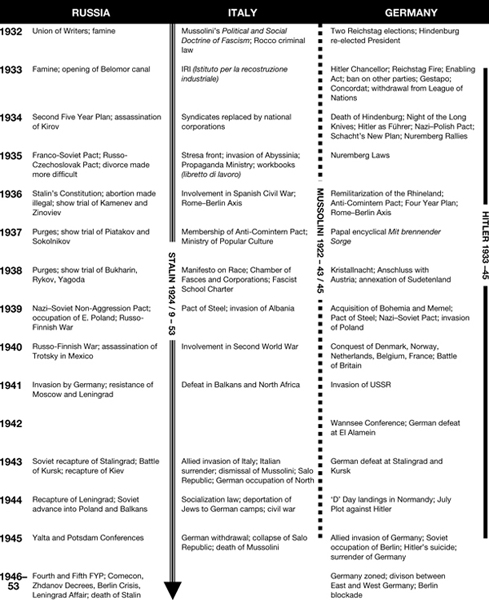

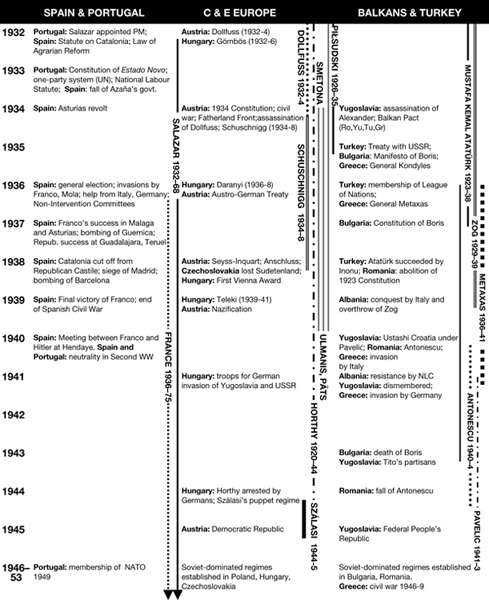

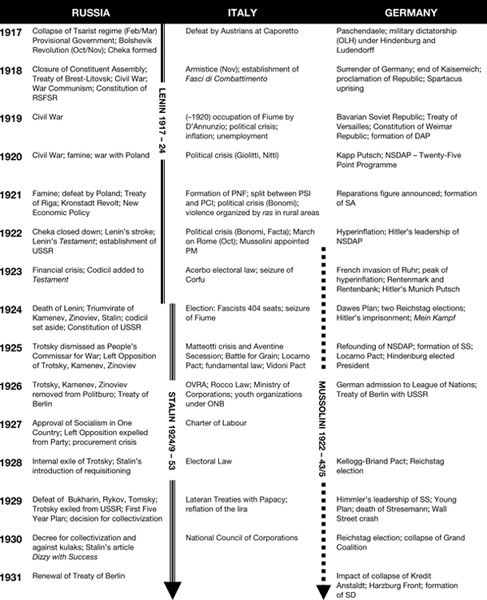

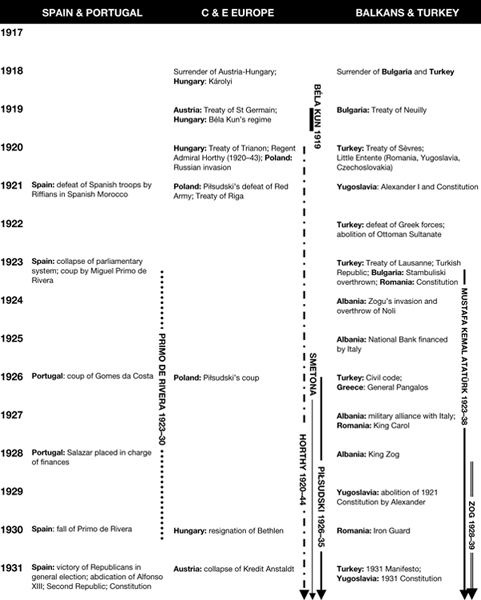

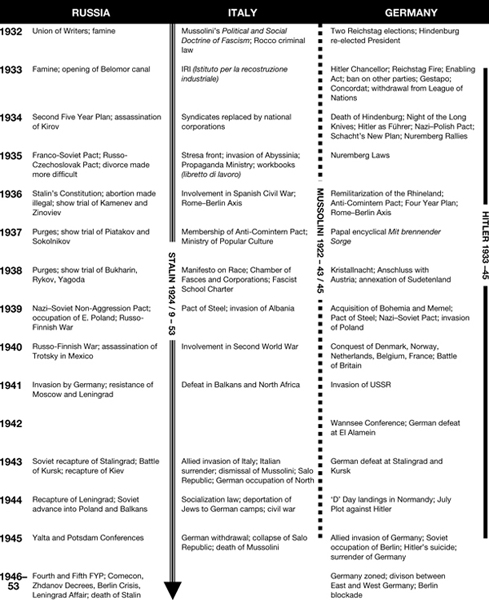

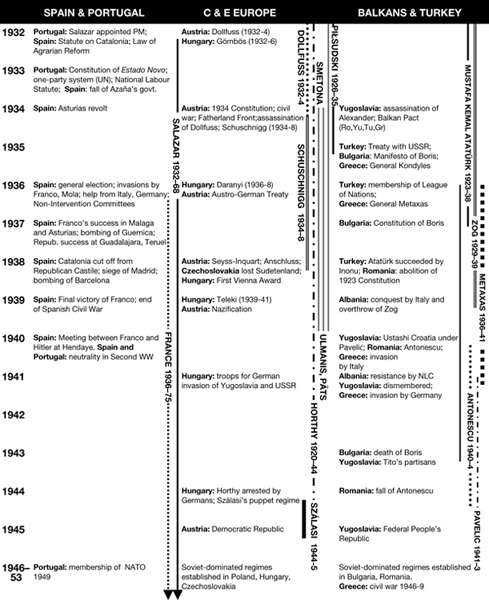

Comparative Timeline 191845

Dictatorships: comparative timeline 191845

Prologue

The seventeen dictatorships, 191845

Europe between the two world wars consisted of a total of twenty-nine states. In 1920 all but three of these could be described as democracies in that they possessed a parliamentary system with elected governments, a range of political parties and at least some guarantees of individual rights. By the end of 1938, no fewer than sixteen of these had become dictatorships. Their leaders now had absolute power which was beyond the constraints of any constitution and which no longer depended upon elections. The dictators sought to perpetuate their authority by removing effective opposition, by restricting personal liberties and by applying heavy persuasion and force. Of the remaining twelve democracies, seven were torn apart between 1939 and 1940. Thus, by late 1940, only five democracies remained intact: the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, Finland and Switzerland (see ).

Map 1 The European dictatorships 191838/40

The first dictatorships were those of the far left, and involved the use of the term dictatorship of the proletariat to indicate a phase in the development of the principles of communism (see p. 30). Lenin established the Bolshevik regime in Russia in October 1917 after the overthrow by force of the semi-liberal Provisional Government which, in turn, had disposed of the Tsarist Empire in March. Lenins dictatorship was subsequently enlarged by Stalin, who came to power in 1924. Meanwhile, Hungary experienced a communist revolution in 1919 as Bla Kun tried to repeat the Bolshevik achievement. His regime, however, lasted only 133 days and eventually fell to counter-revolutionary forces. Although there were to be further attempts at installing a dictatorship of the proletariat in several other European countries during the 1920s and 1930s, none succeeded.

In fact, all but one of the other dictatorships came from the right of the political spectrum. Two of these, the most powerful, have been described as revolutionary. In 1922 Mussolini set the pattern for a number of other leaders by assuming control of Italy, and proceeded to impose the basic principles of Fascism. Eleven years later, in 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor in Germany and established a more ruthless regime the Nazi Third Reich. Italy and Germany, initially rivals for control over central Europe, developed from the mid-1930s a working diplomatic partnership known as the RomeBerlin Axis. With this they spread their influence widely in an effort to undermine the remaining democracies on the one hand and, on the other, to checkmate Soviet Russia.

The right also produced a series of more conservative dictatorships; these are often called authoritarian, in contrast to the totalitarian regimes of Italy and Germany and, indeed, of Stalins Russia (see reorganized after the First World War, succumbed to a series of strong men who promised an escape from the chaos of party conflict or the threat of communism. Hence, Horthy established control over Hungary in 1920 and Pisudski over Poland in 1926. Austria moved to the right in 1932 under Dollfuss, whose regime was continued by Schuschnigg from 1934 until Austrias eventual absorption into Germany (1938). Even the tiny Baltic states adopted an authoritarian system: Lithuania fell to Smetona in 1926, Latvia to Ulmanis in 1934 and Estonia to Pts in the same year.

Dictatorships also emerged in all the states of south-eastern Europe, or the Balkans. Four of these were monarchies: Ahmet Zogu proclaimed himself King Zog of Albania in 1928; King Alexander assumed personal control of Yugoslavia in 1929; King Boris followed suit in Bulgaria in 1934; and, finally, King Carol dispensed with parliamentary government in Romania in 1938. The fifth Balkan state, Greece, experienced under Metaxas (193640) a more systematically organized form of authoritarianism which was influenced to some extent by Nazi methods.

The Iberian peninsula, meanwhile, had produced three strong men. The first was General Miguel Primo de Rivera, Spanish dictator between 1923 and 1930. His regime, it is true, was succeeded by a democratic republic but this, in turn, was brought down by General Franco who led the Nationalists to victory over the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. This conflict, which lasted from 1936 to 1939, also gave an opportunity to Hitler and Mussolini to pour military support into Francos war effort and launch a combined offensive against the leftist supporters of the Republic; it did much, therefore, to increase the confidence and aggression of German and Italian diplomacy. Portugals experience was less turbulent. From 1932 she was under the iron rule of Dr Antonio Salazar, who remained in power until 1968.

Next page