For Mum and Dad

And in memory of James Peterson, 19041980

who endured and survived the events in this book

CONTENTS

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

Appendix I |

Appendix II |

Appendix III |

Appendix IV |

I have received help and advice from various people and organisations who have given me information, documents or photographs and I would especially like to acknowledge the assistance of the National Archives at Kew and the Tyne and Wear Archives Service. Being able to remotely search and order copies of documents and photographs that could only otherwise have been studied in person is an incredible service and we are very fortunate to have it.

I would like to thank Ian Wilson for what has been an inestimable and invaluable contribution to this book. From the very beginning he provided me with documents, photographs and ideas, some of which I could never have hoped to find without him. He has been incredibly generous in sharing information with me and this book would have been much poorer without his help.

I would also like to thank Leigh Bishop for the help and information he gave me, and for allowing me to use his stunning wreck photographs in the book. Seeing Empire Heritage in her final resting place helps to add another dimension to the story.

And finally, thanks to Shelley, without whose endless love and support this book would never have been written.

Out in the blustering darkness, on the deck

A gleam of stars looks down. Long blurs of black,

The lean Destroyers, level with our track,

Plunging and stealing, watch the perilous way

Through backward racing seas and caverns of chill spray.

One sentry by the davits, in the gloom

Stands mute: the boat heaves onward through the night.

Shrouded is every chink of cabined light:

And sluiced by floundering waves that hiss and boom

And crash like guns, the troop-ship shudders doom.

Night on the Convoy, Siegfried Sassoon

At 0350 hours, in the early morning darkness of Friday 8 September 1944 the sea moved with a moderate swell in the north-westerly force 4 off the north coast of Ireland near County Donegal. The moon had shone intermittently throughout the night and early morning; there had been some cloud cover but it was generally clear and visibility was good. Sunrise would be in another two hours. The cliffs of Malin Head, the most northerly point of Ireland, were black, rugged silhouettes, and there was no movement but that of the sea. The only sound inshore was of the wind and waves. Some fifteen miles out to sea, the night was disturbed by huge black forms moving in from the west. Enormous shapes of steel and the rumble of massive steam engines moved through the dim air, frothing bow waves spread across the water creating white-tipped trenches on the murky morning surface. This was the darkness before the dawn.

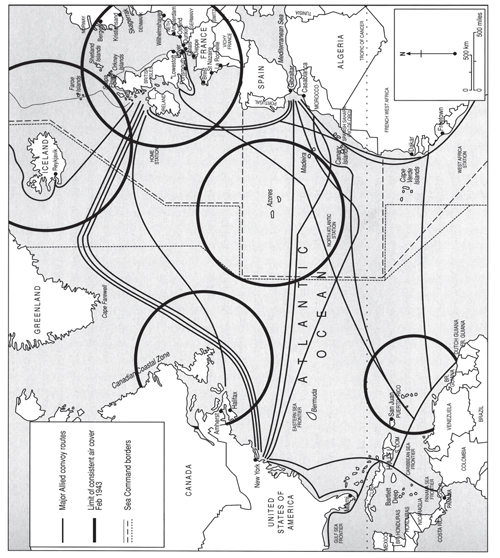

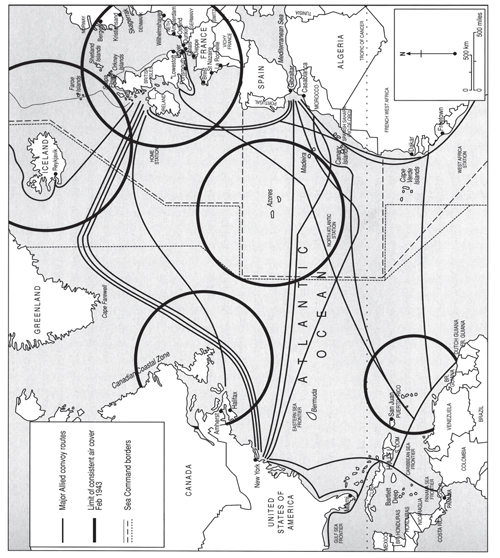

An enormous convoy of ships slid east from the Western Approaches towards the North Channel, the narrow strait between Scotland and Ireland on its way to Britain. They were at the final stages of a voyage that had taken them across the North Atlantic from the east coast of the United States and Canada. The main convoy was composed of no fewer than 98 vessels, a variety of ships of all types, shapes and sizes, sailing together for the protection of safety in numbers and surrounded by an escort of armed ships. Collectively, the motley group was called HX-305, one of the thousands of supply convoys that moved across the world and converged on Britain throughout the Second World War. In the holds of these ships lay the necessary supplies to sustain the British people in this desperate time and supply the Allied forces with fuel and weapons for the continuing conflict in Western Europe.

The majority of the ships were American, though there were also British, Dutch, Norwegian and Panamanian vessels amongst the convoy, sailing from New York or Nova Scotia to Liverpool, before dispersing to other ports across the country such as Manchester, Cardiff, Hull, Belfast and the Clyde, amongst others. They carried cargoes of grain, foodstuffs, lumber, paper, fuel and mail for the British population, alongside weapons, ammunition, trucks, tanks and oil for military use. In addition, they carried a large number of passengers, including many naval personnel who had lost their ships on previous voyages and who were heading back across the Atlantic to join new ones. They were known as DBS or Distressed British Seamen. The most common reason for these men losing their ships was enemy action, and the most common perpetrator of those actions was the deadly U-boat.

By September 1944 U-boat activity in the North Atlantic was greatly reduced, having steadily tapered off over the previous fifteen months. Compared to the early days of the war, the U-boat threat was becoming negligible. Only a handful of merchant ships had been lost that year, a massive difference to the enormous losses suffered in 19401943 when U-boat successes had been at their height. In fact not a single ship had been lost to enemy action in an HX convoy since 22 April 1943, nearly seventeen months before. In previous years attacks had been much more frequent and deadly; for example, in 1942 the Allies had lost 124 ships in a single month and over 1,000 ships over the course of the year. Such losses represented an enormous number of men and shipping tonnage, lost forever beneath the freezing Atlantic Ocean, their holds full of supplies that would never serve their purpose. But by September 1944, as convoy HX-305 cruised east along the coast of County Donegal, successful U-boat attacks were at their lowest since the beginning of the war and developments in anti-submarine technology had given the Allies the upper hand. Also, the Allied invasion of Europe that had begun on D-Day had robbed Germany of her important U-boat bases along the Bay of Biscay. The subsequent breakout from Normandy and eventual liberation of France by the Allies meant that Germany had been forced to evacuate these bases and retreat her U-boats to her other occupied coasts such as Norway, or to Germany. This reduced her access to the Atlantic and meant a much longer trip for her U-boats trying to intercept Allied shipping as it moved through the Western Approaches.

But even though the Third Reich was rapidly unravelling and the Allies were edging ever closer to Berlin, the U-boat arm of the German Navy had proved itself notoriously determined and though the frequency and success of their attacks had certainly been diminished, the U-boats were still very much operational. In the previous two weeks at the end of August and beginning of September 1944, a number of unexpected and successful attacks had taken place in the coastal area where HX-305 was now sailing and three Allied ships had been sunk; a large American tanker, a Norwegian freighter and a Royal Navy corvette. Despite an extensive search the attacker had remained undetected and unidentified.

Whilst in Europe the war against Nazi Germany was slowly being won by the Allies, the men of the Merchant Navy had to remain ever vigilant, and could not for one moment forget the threat that the U-boats continued to represent. In late 1944, the tide had turned against Germany in nearly all the theatres of war, including the longstanding Battle of the Atlantic, but the Allied seamen were still sailing in almost constant danger.

Next page