The Real Dirt On Vegetables

Farmer John Peterson

The Real Dirt On Vegetables

Digital Edition v1.0

Text 2006 Farmer John Peterson

Photos 2006 John Peterson and Angelic Organics except: pages 121, 237, and 269 2006 Taggart Siegel pages 63 and 142 courtesy Johnnys Selected Seeds

*Material presented in Farmer Johns Cookbook is from a wide variety of sources on an impressive range of subjects. Some excerpts appearing in this book have been given new titles that more accurately reflect the content of the quoted text. These descriptive titles are enclosed in quotation marks and will hopefully assist the reader in navigating the essays.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith, Publisher

PO Box 667

Layton, UT 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

Library of Congress Catalog-in-Publishing Data

ISBN-13: 978-1-4236-0014-5

ISBN-10: 1-4236-0014-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2006920206

This book is dedicated to the farmers who work with the earth lovingly, and to those who support these farmers and the earth itself through their choices.

Preface and Introductory Material

I dont know if it was the lime or the Biodynamic herbal sprays we used extensively last season or the subsoilingbut the soil has turned into something wonderfully different from last years cement. The ground is spongy, almost bouncy as you step on iteven after a rain, and even after it has been worked with the tractor. Im so glad to know that the roots of all the vegetables get to play around in that paradise. On some level its got to make the plants happy. And maybe on some level, while youre eating them, your vegetables will do the same for you.

Farmer John, Harvest Week 1, 1994, Newsletter

Preface: A Life of Farming

Farming from a Young Age

Ive been farming for over forty years on the same farm. I started in 1956 when I was seven, taking care of the chickens. By age nine I was milking seventeen cows twice a day.

By the mid-sixties, many of the homey little farms that dotted the countryside were either going through expansion in order to survive or were closing their barn doors. The Peterson farm went the expansion route, until financial calamity arrived in the early 1980s and almost closed the farm down for good.

However, enough of my land survived the shakeout to build anew. In the late eighties, I began to imagine a natural system by which to farm, a system in which results were derived from the integrity of the soil, not the shenanigans of crop chemicals and petroleum-based fertilizers. I envisioned a system that married me to the land, not divorced me from it. By this time, I had seen too many people on drugstheir personalities hardly recognizable, their voices slurred, their eyes glazed. I resented drugs. Drugs concealed who people were. I didnt want drugs concealing what my crops were.

And what are farm chemicals but drugs by a different name? Consider that anhydrous ammonia, the most common petroleum-based nitrogen fertilizer, is routinely stolen in the countryside and used to make methamphetamine, a brutal form of speed. (Other uses of anhydrous ammonia? It was used extensively during World War II for the task of turning soil into rock-hard landing strips. It also was an essential ingredient in making explosives.) I sought more benign inputs for my new farming operation.

Angelic Organics was reborn out of my great losses of the 1980s, reborn with an eye to the well-being of the earth we live on and the food we eat. The farm slowly got its footing in the challenging new world of organic vegetable production. Why slowly? The organic approach required looking at underlying causes of plant healthnot just shotgunning chemicals at the crops to fix problems. It required looking at fertility from the standpoint of natural processes, learning how to work with green manures, compost, and fallow land. It necessitated a comprehensive and complex system of weed, blight, and insect control, and raising more than fifty different types of vegetables and herbs meant accommodating numerous rhythms within one farming operation: learning the needs of each vegetable, how to seed it, tend it, harvest it, clean it, and store it. This was a far cry from the simple days of raising corn and beans and hay, of tending cattle and hogs with straightforward, widely available technology. Raising vegetables organically required much more hand labor, a whole different set of technology, a revamping of facilities, and a vastly different farming mind-set. This transition required many one-hundred-hour workweeks from me in the first several years of vegetable farming. I had to learn on the fly how to integrate all of the newness into the farm in a way that would make it survive in the marketplace.

Seeking a truly comprehensive approach to farming, one that went even beyond organics, I began learning about Biodynamics, a practice and a philosophy that conceives of the farm as a living organism. (To learn more about Biodynamics, see Andrew Lorands essay )

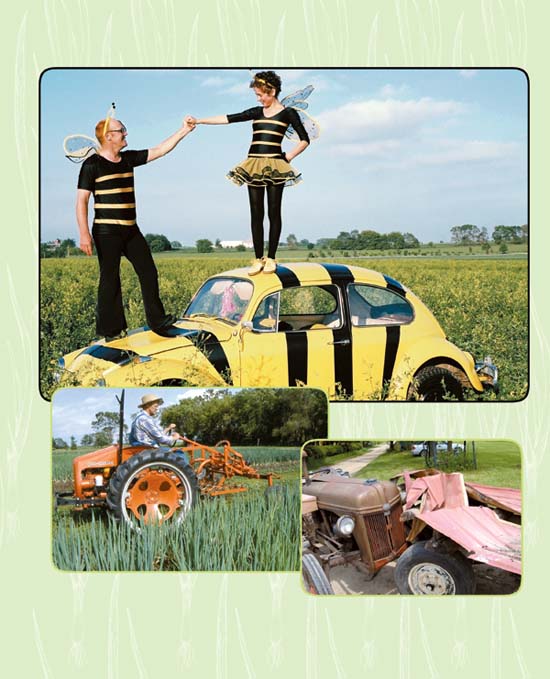

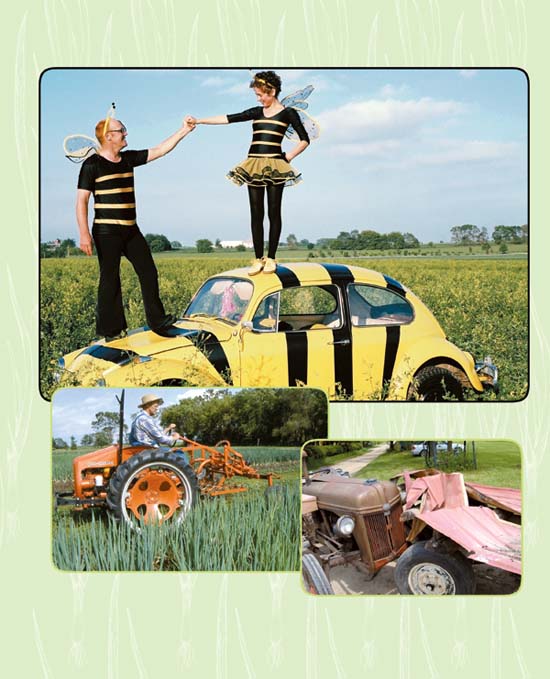

Farmer John and Assistant Editor Lesley Littlefield Freeman, Allis G tractor, metal meets metal

The Farm Today: Community Supported Agriculture

My way of farming is not just about growing vegetables. It is also about building relationships between the farm and the people who receive our vegetables. For my whole adult life, I have been fascinated with farming, with farms, and I have always loved to bring non-farm people into the mysterious, dynamic sphere of agriculture through farm tours, writing and telling stories, and raising food. And what better way to include people in farming than Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)? It is a new socioeconomic form in which the farmer and consumer enter into a sort of partnership, an alliance to take care of each others needs. This results in an annual contract in which the farmer agrees to provide a seasons worth of vegetables to the consumer (usually known as a shareholder). The shareholder gets a taste of farm life through his or her relationship with the farmthrough the vegetables, our newsletter, farm-based events, and perhaps occasionally volunteering to work on the farm. Reciprocally, the farmer gets an ongoing relationship with his or her shareholders via the long-term arrangement for providing their vegetables.

Although many shareholders visit our farm each year to participate in open houses and to volunteer, few are able to enjoy sustained, personal contact with our soil and with our farm team. Its true that eating food from the farm each week builds a very tangible connection, but unlike crew members who work on the farm, shareholders are unable to witness the growth of all the seedlings, the ripening of all the eggplants, the harvest of all the melons.

One tool weve used to bridge the gap between our fields and our shareholders kitchens is our weekly newsletter. Over the years, the essays and farm updates in those newsletters have brought Angelic Organics home to our members, helping them get to know the farmers and staff who grow their food; giving them tours of our fields in rain, sun, wind, and snow; and welcoming them as virtual guests at farm social gatherings. Shareholders read about the groups that visit Angelic Organics through the CSA Learning Center, a not-for-profit educational organization based on the farm (see www.CSALearningCenter.org), and they learn about issues and current events in the world of food and agriculture that are important to them and their farmers.