To our early box customers, whose support, trust and love of food allowed me to farm the way I wanted to. GW

For David and Mandy (who, for the record, are not box customers). JB

The Riverford dynasty emerged in the post-war years out of the marriage of a fantastic cook and a determined young farmer. Fifty-five years later it is still a family business, with all five of the second generation applying the values we inherited from our parents in the search for a saner way of producing, distributing and enjoying food.

The patriarch

When the recently demobbed, idealistic and pitifully inexperienced John Watson took on the Church of England tenancy of Riverford Farm in 1951, his more traditional farming neighbours confidently predicted he wouldnt last five years. Food rationing was coming to an end and British agriculture was embarking on a new era of chemically driven intensive farming. For 25 years Riverford was at the forefront of these changes, even at one time being a demonstration farm for ICI. But by the 1970s my father was increasingly questioning the sustainability and animal welfare involved in some of the more intensive practices. By the 1980s the door was open for the next generation to take the farm in a different direction.

The matriarch

Perhaps even more significant to the shape of Riverford today was the influence of our mother, Gillian, who married John and moved to Riverford in 1952. It was her irrepressible enthusiasm for food and cooking that laid the foundations for the food businesses run by their five children today.

Their children

There was no overt pressure for us to continue in food and farming, but it was deeply instilled in us that we should do something useful with our lives, and nothing else seemed to make the grade. Over the years, those of my siblings who had gone away have drifted back to continue and broaden the farms activities, now into a third generation.

First Ben, complete with law degree but recognising that he would be stifled in a wig, started experimenting with curing bacon in the garage. Thirty years later he has three shops and a substantial home-delivery business supplied by his own pies and preserves, butchery and bakery.

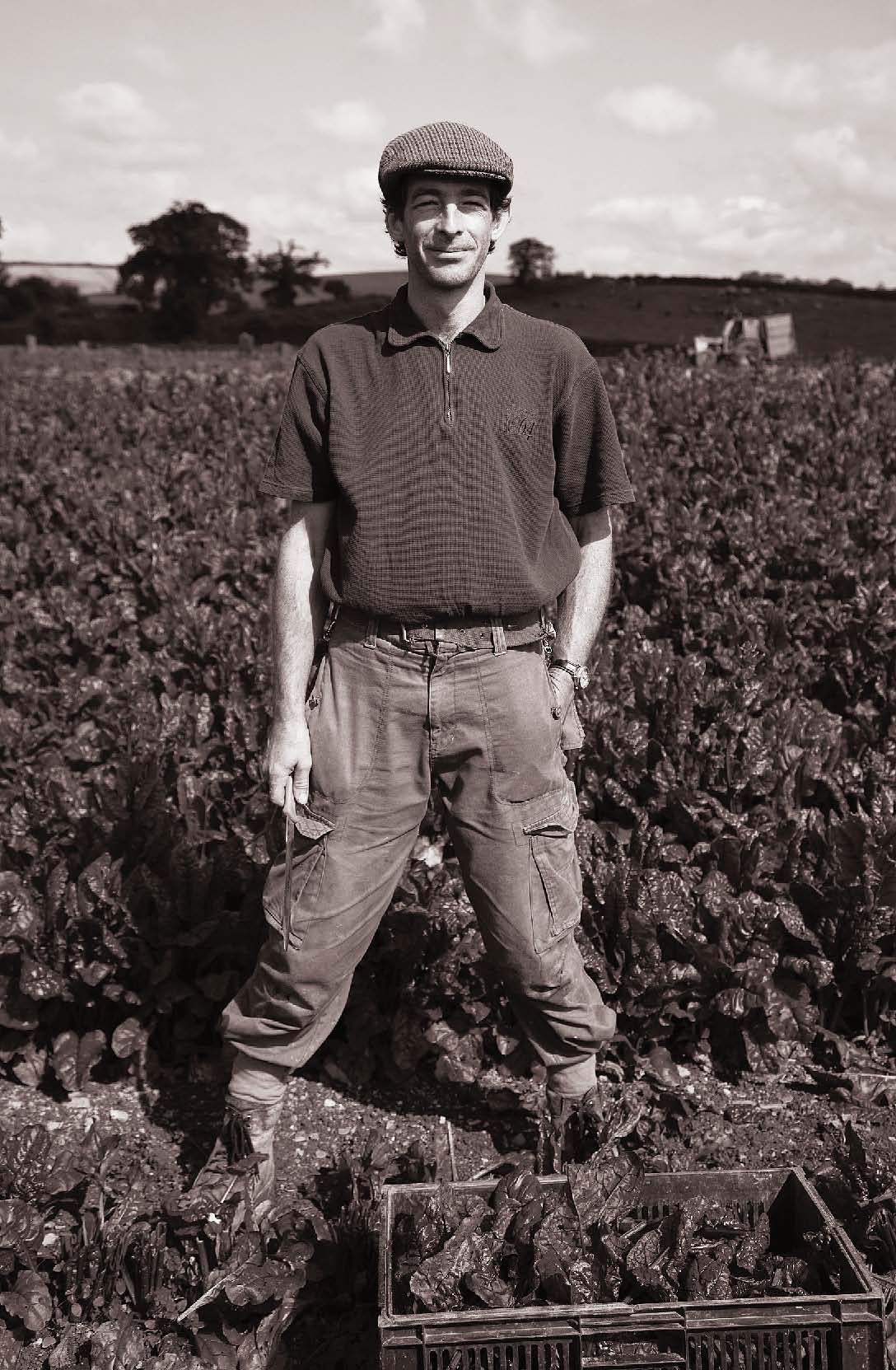

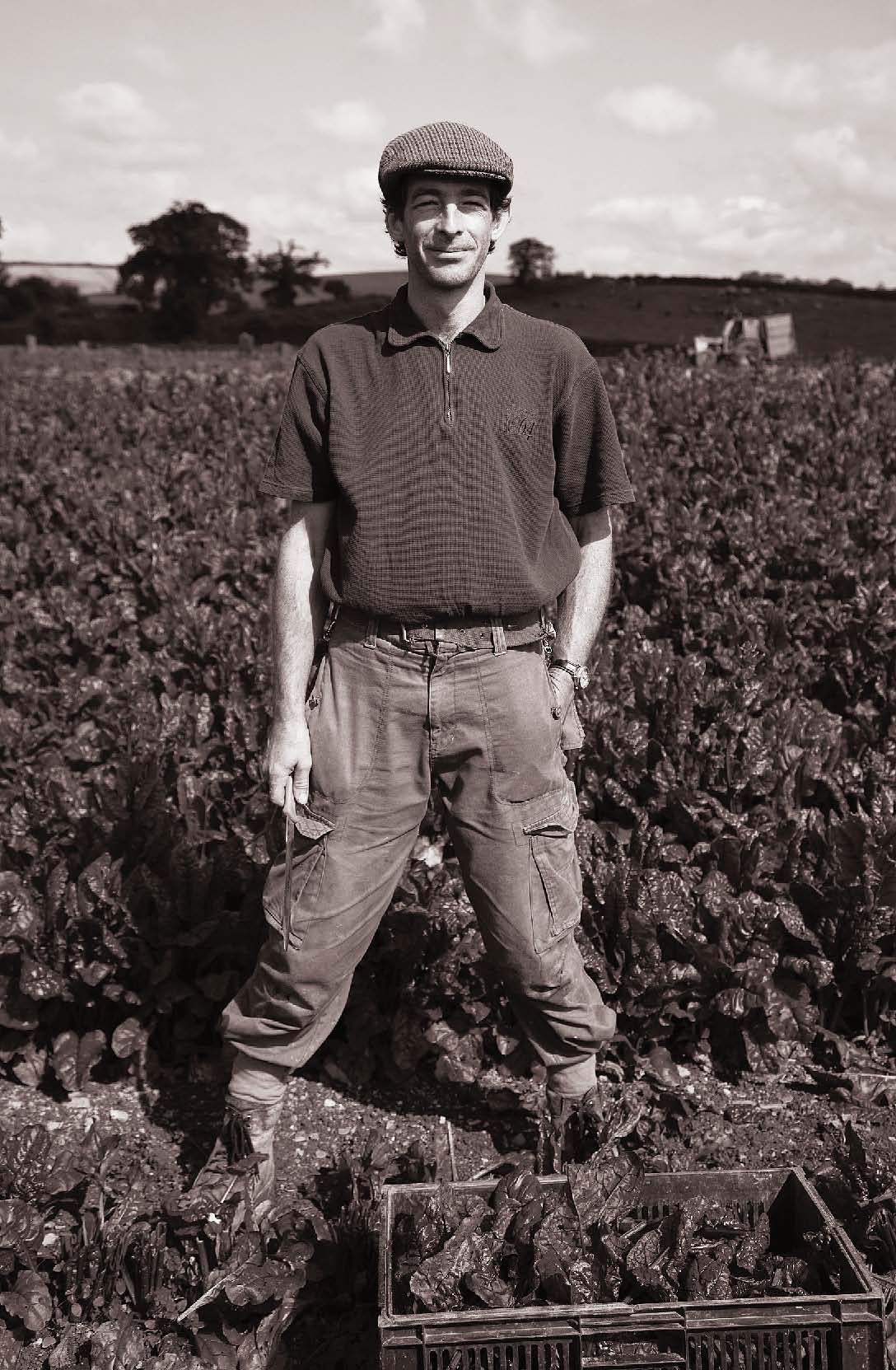

I was the next to return, after a brief spell as a management consultant in London and New York, and was responsible for setting up the vegetable box scheme and starting the Field Kitchen. Meanwhile, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Oliver and Louise expanded the farm, developing the dairy and moving to extensive, organic production methods, complete with their own milk, yoghurt and cream business. Rachel was the last of the five to return to the farm, after a marketing career in London, and is now involved in developing the marketing of the vegetables and farm shops.

Vegetable boxes

As the vegetable business developed during the 1980s, we started looking beyond local shops. Supermarkets were just starting to stock organic produce and it was inevitable that we would eventually end up selling through them. This brought scale and forced a more professional approach, but working through such a wasteful supply chain was hugely frustrating; seeing our vegetables devalued through age, distance, excessive packaging and anonymity, while trebling in price, made me think there must be a better way. A meeting with Tim and Jan Deane, founders of the first box scheme in the UK, sowed the seed but it was the enthusiastic response of my first customers on the doorstep that really convinced me to change paths.

The first vegetable box was delivered in 1993 and since then home delivery has enabled us to break free from the clutches of the supermarkets and to relate directly to our customers. The early boxes were very basic and it soon became obvious that we would need to broaden our range and season if we were to appeal to more than a small band of hard-core local veg-heads. We put up polytunnels, experimented with new crops and eventually started trading with farmers abroad to keep the boxes interesting throughout the year. Initially my staff were sceptical. Planting and picking the small, fiddly quantities that the boxes demanded was an unwelcome complication after loading lorries with white cabbage, but the appreciative comments of customers, in contrast to a supermarket buyers abuse, converted everyone. Like the Field Kitchen that followed, the box scheme has been the way to make the best food accessible and affordable to all, and to share our enthusiasm for food and cooking.

Why organic?

Having made myself sick spraying corn as a teenager, and seen my brother committed to hospital with paraquat poisoning, my initial motivation for farming organically was simply a personal desire to avoid handling pesticides. At the back of my mind, there was also a hunch that it offered better long-term financial prospects than adding to the lakes and mountains of overproduction that pervaded the EU in the 1980s.

During the early years there were numerous mistakes and frustrations but I came to relish the challenge of finding my own solutions to agronomic problems rather than following the prevailing belief that the answer to every difficulty lay in a chemical container. Latterly, this has evolved into a belief that we must find a more harmonious and holistic way of living within the limits of our planet. The problems faced by food and farming now have more to do with culture than with science. Organic farming, in its broadest sense (working from the underlying principles rather than just following the minimum standards for certification), provides the best framework available for finding answers to those problems.

Co-operation

By the late 1990s we were no longer regarded as freaks by our neighbours and a few were open to the idea of organic farming. In 1997 ten (now16) local farmers joined us to form the producers cooperative, increasing production to keep pace with the expanding box scheme.

Next page