THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

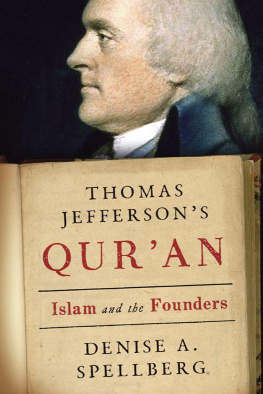

Copyright 2013 by Denise A. Spellberg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Johns Hopkins University Press for permission to reprint an excerpt from The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller by Carlo Ginzburg, translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi. Copyright 1980 by The Johns Hopkins University Press and Routledge Kegan Paul Ltd. Reprinted by permission of The Johns Hopkins University Press.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-385-35053-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spellberg, D. A. (Denise A.)

Thomas Jeffersons Quran : Islam and the founders / Denise A. Spellberg. First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-307-26822-8 (hardcover) 1. Jefferson, Thomas, 17431826Political and social views. 2. Jefferson, Thomas, 17431826Religion. 3. MuslimsCivil rightsUnited StatesHistory18th century. 4. Islam and politicsUnited States. 5. Freedom of religionUnited StatesHistory18th century. 6. Constitutional historyUnited States. I. Title.

E332.2.S65 2013

973.46092dc23 2013010153

Cover images: (top) Thomas Jefferson by James Sharples (detail) Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library; (bottom) Jeffersons copy of the Quran, George Sales, trans. (detail), Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.

Cover design by Joe Montgomery

v3.1

In memory of those who arrived first:

Sebastiana Campochiaro Pavone and Antonio Pavone

&

Dvira Goldman Spellberg and Zvi Hersch Spellberg

And for all my students, with hope

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

Leviticus 19:3334 (New JPS Translation)

O NE RAINY A PRIL MORNING in 2011, I requested Thomas Jeffersons Quran from the Rare Book Room in the Library of Congress. Outside, tulips blazed in bright patches of red around the Capitol building. The flowers reminded me of their origins in the Ottoman Empire. The sultan had first sent them as diplomatic gifts to European rulers in the sixteenth century, and by the mid-seventeenth, the trade in the bulbs of these plants had reached a frenzied pitch in the Netherlands. And so it was that, through contact with Muslims long ago, this stunning flower had eventually reached North America, where it now reigns as a sign of spring.

Summoned with nothing more than the requisite library card and the relevant call number, the two volumes of Jeffersons Quran arrived unceremoniously at my desk in less than ten minutes. I sat amazed. A national treasure was mine to peruse. As a historian and a citizen, Id thought for years about what Jeffersons Quran might have meant. Now, suddenly, I could touch the brown leather bindings, and hear the slight crackle of the yellowing pages as I turned them. The volumes were far too delicate, I thought, to be touched by anyone. I could not help but recall that eight months earlier in Florida an addled pastor of a The Florida minister believed he was exercising his First Amendment right to express how execrable he thought Islam was. Inadvertently, he revealed how little he knew about the historical importance of the Quran to Protestants in both Europe and America. For them, it had been more common since the seventeenth century to translate the sacred text for Christian readers than to consign it to the flames.

For me, the pages of Jeffersons Quran represented sacred historical evidence, not of the truth of Islam, but of the capacity and eagerness of some early Americans to learn about that faith. As a professor of Islamic history, I wanted to know what early Americans knew about Islam and how theyd learned about the religion and its history. To my surprise, I found that many Americans in the founding era, despite the tenacious legacy of misinformation from Europe, refused to yield to contemporary fears promoting the persecution of Muslims. They preferred to be heirs to a less prominent but important strain of European tolerance toward Muslims, one whose influence had thus far been overlooked in early American history.

Jeffersons two-volume English translation of the Quran had grabbed the national spotlight in January 2007, when Keith Ellison, the countrys first Muslim congressman, chose to swear his private oath of office on the Founders sacred text. At the time, I thought that the outrage expressed by some toward Congressman Ellisons election and private swearing-in on the Quran might have been averted if only more Americans had known their own founding history better, a past that had prepared an eventual place for Congressman Ellison, not in spite of his religion, but because of it.

The idea of the Muslim as citizen and federal officeholder is not new to the United States. It was first considered in the eighteenth century. Yet today some claim that even the concept of a Muslim citizen in elected office is threatening to the nations identity. I argue the opposite in this book: The concept of the American Muslim as citizen is quintessentially evocative of our national ideals. Indeed, the inclusion of Muslims as future citizens in early national political debates demonstrates a decided resistance to the idea of what some would still imagine America to be: a Christian nation.

This book about the American past began accidentally for me as a specialist in Islamic history. Initially, Id wondered why a French play, ostensibly about the Prophet Muhammad, had been performed in Baltimore during the Revolutionary War. To make sense of this more than a decade ago, I had the privilege of attending the ideal summer school: Professor Bernard Bailyns International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World at Harvard University. I took to paddling in this new Atlantic pond and found that the experience had prompted a sea change in my academic research, which I incorrectly assumed would be temporary.

By 2005, at the Atlantic Seminars tenth-anniversary conference, I had found a new document about Muslims in early American political debates. Again, I was fortunate to be invited to present this research to fellow students of Atlantic history. Professor Bailyns thoughtful, enthusiastic response to my ideas about Thomas Jefferson and his views of Muslim rights was rooted in his deeper knowledge of these constitutional sources. His interest in these ideas convinced me that what people thought about Muslims as citizens in 1788 should be included in the study of the Constitution. Did more data about Muslims as potential citizens in the founding era exist? Over the next seven years, I learned the breadth of that affirmative answer.

By the time Congressman Ellison was elected and swore his private oath of office on Jeffersons Quran in 2007, I thought as a historian that I might have something to contribute, beyond the fact of Jeffersons mere ownership of the Islamic sacred text. I wanted to know why Jefferson and others had included Muslims in the nations nascent ideals. At this juncture, Professor Bailyn introduced me to Jane Garrett, his kindly, patient editor at Knopf.