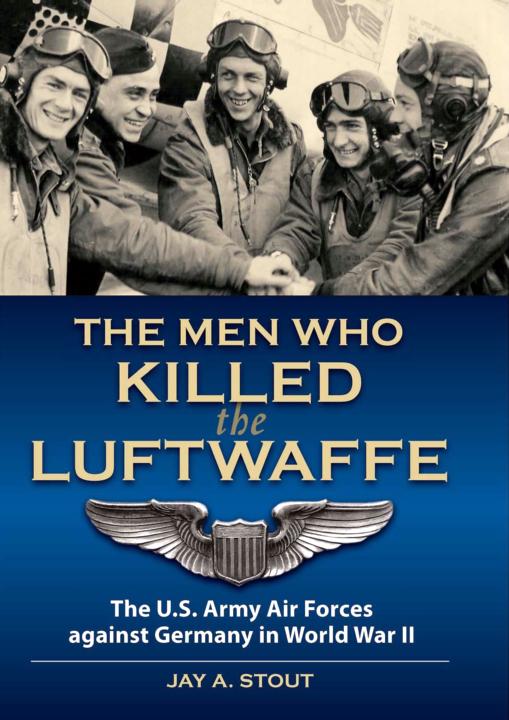

Jay A. Stout

pring 1934. Fourteen-year-old William Heller settled himself into the "cockpit" of his homemade glider and took one last look at the lath-and-wire contraption. It seemed sufficiently airworthy. Its wings, sheathed in linoleum tablecloths, looked large and sturdy enough to lift him airborne.

pring 1934. Fourteen-year-old William Heller settled himself into the "cockpit" of his homemade glider and took one last look at the lath-and-wire contraption. It seemed sufficiently airworthy. Its wings, sheathed in linoleum tablecloths, looked large and sturdy enough to lift him airborne.

He squinted up at his friend "Squee" Miller who sat at the wheel of the pickup he had taken from his parents' nursery. A sturdy rope ran from the truck back to where Heller sat. He gave Squee the prearranged signal, and the pickup whined and bucked and lurched forward. The rope snapped tight and snatched Heller and his makeshift craft across the grass at a quickly accelerating rate.

Heller's heart beat fast as the glider scraped and bumped and careened along the ground. Finally, the nose pointed skyward for just a brief instant before one of the wings dipped, caught the ground, and cartwheeled the little plane into a disintegrating ball of wire and wood and linoleum sheeting.

It was not too long before Mr. Heller arrived with a pair of dikes and set about cutting the bloody boy out of his ill-considered dream. Finished, he stood his son up, looked him in the eyes, and declared: "Next time you fly, you better have an engine!"

Heller would eventually fly with four engines, and rather than bump along a Pennsylvania cow pasture, he would deliver bombs deep inside Hitler's Germany. Although none of them knew it that spring of 1934, tens of thousands of his peers from around the nation would be flying with him.

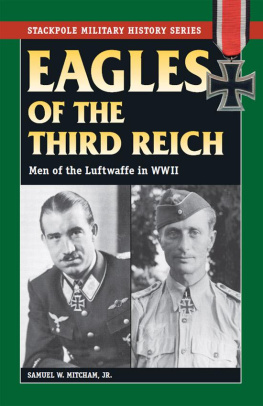

o period in the history of air warfare is a more fertile field for writers and scholars than the fighting that raged over Europe during World War II. It was remarkable not only because of its its magnitude, but because the stakes were so high. The air war against Nazi Germany had to be won before Europe could be liberated. Beating the Germans in the air was a gargantuan effort made up of hundreds of major elements, any one of which deserves book-length treatment. In fact, hundreds of books have been written about the fight against the Luftwaffe, the German air force.

o period in the history of air warfare is a more fertile field for writers and scholars than the fighting that raged over Europe during World War II. It was remarkable not only because of its its magnitude, but because the stakes were so high. The air war against Nazi Germany had to be won before Europe could be liberated. Beating the Germans in the air was a gargantuan effort made up of hundreds of major elements, any one of which deserves book-length treatment. In fact, hundreds of books have been written about the fight against the Luftwaffe, the German air force.

Capturing every component of that air war in a single work is impossible; there is simply too much material. Likewise, there are too many key personages. What I aim to highlight here are the experiences of individual airmen, mostly unknown, who were representative of the enormous numbers of young Americans who made up the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) during the air war over Europe. Accordingly, in order to maintain a sharp focus on these airmen, I have purposely refrained from mentioning the literally hundreds of outstanding leaders without whom the fight might have been lost.

By the time of my childhood in the 1960s, most of these unheralded airmen had long before hung up their uniforms and made civilian lives for themselves. They piqued my schoolboy interest with an occasional story or offhand reference. I was struck that these men who seemed so unremarkable were the ones that had fought the war over Europe. But now, older and with a military flying career of my own fading into memory, I understand and appreciate these men in a way that I could not when I was a child. And I want to honor them. Accordingly, I have crafted a framework of strategy and doctrine, of tactics and equipment, of time and place, of well-known leaders to showcase how they beat the Luftwaffe-since it was mostly the USAAF that defeated the Luftwaffe.

But what about Great Britain's Royal Air Force, the RAF? How can I justify crediting the killing of the Luftwaffe to the United States? First, there is no doubt that Great Britain, America's dearest ally, played a major role in the defeat of the Luftwaffe. I will declare up front that I am a great admirer of the RAF's airmen, and I will further offer that had the men of Fighter Command not turned back the Luftwaffe in the skies over England during 1940, the Nazis might have taken the British Isles and subsequently won the war. But instead, Great Britain's airmen saved not only their nation, but also the base from which the United States later launched its crippling air campaigns. Those raids ensured the destruction of the Luftwaffe, guaranteeing that Hitler's armies never had a prayer of surviving the war, much less winning it.

Furthermore, the quality and professionalism of the RAF's aircrews was superb; throughout the entire war, Great Britain fielded perhaps the best trained airmen of all the belligerents. Moreover, its equipment was good, technically sound and of high quality. Its night-bombing campaigns burned German cities to ashes and forced the Luftwaffe to commit significant resources, especially night fighters, that could have been useful elsewhere. Its tactical operations, just like many of the USAAF's tactical operations described in this book, had a chronic, if not fatal, effect on the Luftwaffe.

On the other hand, the RAF's leadership did not have a plan for destroying the Luftwaffe. Terror bombing aside, the most the RAF could hope to achieve beyond its own shores-certainly before the United States arrived in strength-was to establish local air superiority above a given battlefield. But even that never happened with certitude when it was really important. The RAF only barely covered the evacuation of Dunkirk, was badly handled during the Dieppe raid, and was never able to push the Germans out of North Africa by itself.

Bomber Command did take the war to Germany, but it did not put together an effective or coherent campaign to target the industries that supported the Luftwaffe. Rather, following a dreadful savaging by the Luftwaffe during a brief and utterly ineffective attempt at daylight bombing, it turned to night raids. Those operations early in the war were simply too inaccurate to deliver the sorts of effects that were required. Consequently, the decision was taken to simply strike Germany's cities in order to terrorize, kill, and "dehouse" the population. Even after Great Britain pioneered night-bombing devices-radar among them-that enabled it to strike with more accuracy, it generally chose to continue flying area-bombing raids rather than hitting specific war-related targets.

pring 1934. Fourteen-year-old William Heller settled himself into the "cockpit" of his homemade glider and took one last look at the lath-and-wire contraption. It seemed sufficiently airworthy. Its wings, sheathed in linoleum tablecloths, looked large and sturdy enough to lift him airborne.

pring 1934. Fourteen-year-old William Heller settled himself into the "cockpit" of his homemade glider and took one last look at the lath-and-wire contraption. It seemed sufficiently airworthy. Its wings, sheathed in linoleum tablecloths, looked large and sturdy enough to lift him airborne.

o period in the history of air warfare is a more fertile field for writers and scholars than the fighting that raged over Europe during World War II. It was remarkable not only because of its its magnitude, but because the stakes were so high. The air war against Nazi Germany had to be won before Europe could be liberated. Beating the Germans in the air was a gargantuan effort made up of hundreds of major elements, any one of which deserves book-length treatment. In fact, hundreds of books have been written about the fight against the Luftwaffe, the German air force.

o period in the history of air warfare is a more fertile field for writers and scholars than the fighting that raged over Europe during World War II. It was remarkable not only because of its its magnitude, but because the stakes were so high. The air war against Nazi Germany had to be won before Europe could be liberated. Beating the Germans in the air was a gargantuan effort made up of hundreds of major elements, any one of which deserves book-length treatment. In fact, hundreds of books have been written about the fight against the Luftwaffe, the German air force.